Phylicia Ghee doesn’t remember a time when she wasn’t making art. As a child, her mother would drop her and her brother off in the mornings at her grandparents’ house in Randallstown on the way to work. Phylicia’s grandfather, Edward Ghee—known to everyone as Ghee; Phylicia calls him Dad—would draw with her all day. “That’s just what I remember—us drawing since I could hold a crayon or a pencil,” she says.

Ghee’s two children are also artists—Edward, Jr. was an illustrator and barber until he became ill and Karen, his daughter, writes poetry—but they didn’t pursue art the way that he has, or the way that Phylicia has, as a full-time commitment. Ghee built his career as a self-taught illustrator and caricature artist in 1970s and ’80s Baltimore. Phylicia, a 2019 Sondheim finalist, is a multidisciplinary artist whose work is inextricably tied to her spiritual practice. Despite a generation between them, the two share kindred qualities as artists and caretakers whose joy and resilience guide their paths. Ghee jokes that before Phylicia was born, he’d “put an order in” for her. “I’m basically him in female form,” she says. Even their hands look alike.

Ghee grew up in an unstable Baltimore home in the 1950s and ’60s. His mother’s boyfriend was abusive, causing his mother to have a nervous breakdown and be institutionalized. Her eight children were divided among family members and Ghee, the eldest, wound up at his biological father and stepmother’s downtown apartment. His father begrudgingly took him in, and school administrators stepped in to aid Ghee’s frequent asthma attacks and severe malnourishment. Ghee recalls his father saying that he was embarrassed to see his ill son walking down the road while driving to work at Sparrows Point. “He ain’t never did anything to make the situation any better though,” Ghee says.

Around age 13, Ghee met Cecelia—known to most as Cee Cee—his wife of almost 60 years. Their relationship was a protective jetty in turbulent times, if a little wobbly initially. “I didn’t like him at first,” Cee Cee says. “Every time I ran into him he was doing something dirty or something stupid.” They eventually got to know each other, talking on the telephone for hours, and Cee Cee invited him to her thirteenth birthday party. Another guy was crazy for her, too, but Ghee arrived at the party before him. “When I got there,” he says, “it was over.” They fell in love and grew up together. Cee Cee gave birth to their first child, Edward, Jr., during Ghee’s last year of high school in 1966.

Ghee excelled at drawing, even though his high school lacked a proper art class. It did have a sign-painting class, where students learned signs could make a quick buck but wouldn’t lead to a job—the first of many discouragements he’d face pursuing an art career. Ghee worked at a drug store in high school, and after graduating and marrying Cee Cee, racist Baltimore offered limited options. As a Black person “back then, if you didn’t work at London Fog you either worked in a post office or you worked at Sparrows Point,” he says. He wound up in London Fog’s advertising department because his asthma kept him out of the warehouse.

A few years later, Ghee sought employment at the ad agency W.B. Doner. His work impressed art director Bill Hunter, who couldn’t offer him a job. Hunter told Ghee to keep looking and come back if nothing else materialized. Everywhere Ghee went said they wanted someone with more education and experience, and he went back to Hunter and laid into him a bit. “They keep telling me the same thing,” Ghee recalls, “but how am I gonna get an opportunity if you aren’t gonna give me an opportunity?”

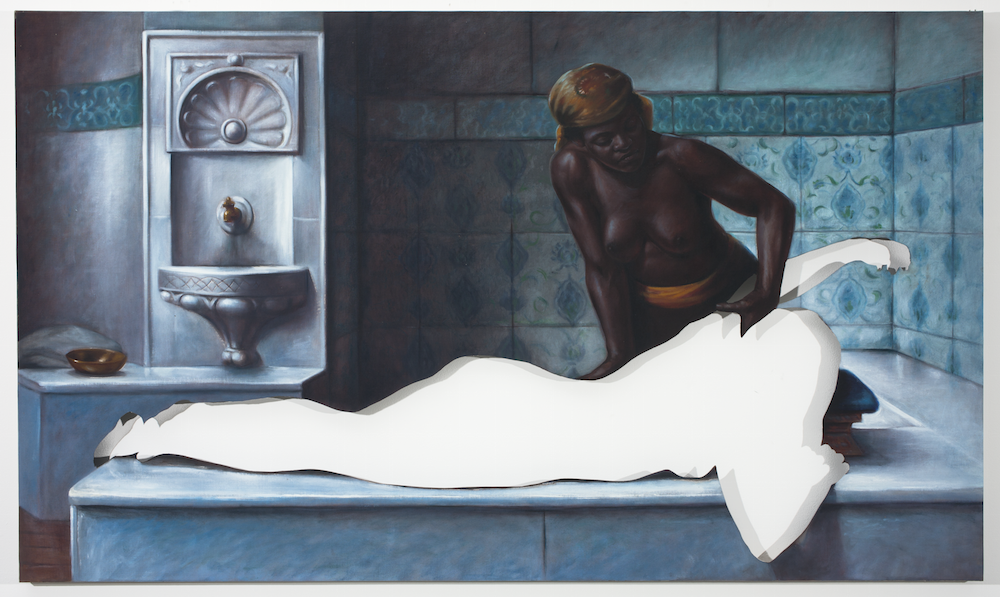

Photograph by Phylicia Ghee from a series honoring her grandfather called “Khepri: I am because You are” currently on view at the African American Museum in Philadelphia in an exhibition entitled In Conversation: Visual Meditations on Black Masculinity

Photograph by Phylicia Ghee from a series honoring her grandfather called “Khepri: I am because You are” currently on view at the African American Museum in Philadelphia in an exhibition entitled In Conversation: Visual Meditations on Black Masculinity

Ghee and Cee Cee, 1970 (courtesy of Ghee family)

He got his start filing art in Doner’s production department and working in the mail room. Carrying his brown-paper portfolio with him one day, Ghee ran into the company’s vice president in the elevator. The VP asked to see his work and thought it preposterous that Ghee was working in the mail room. Hunter promoted him to a junior art director.

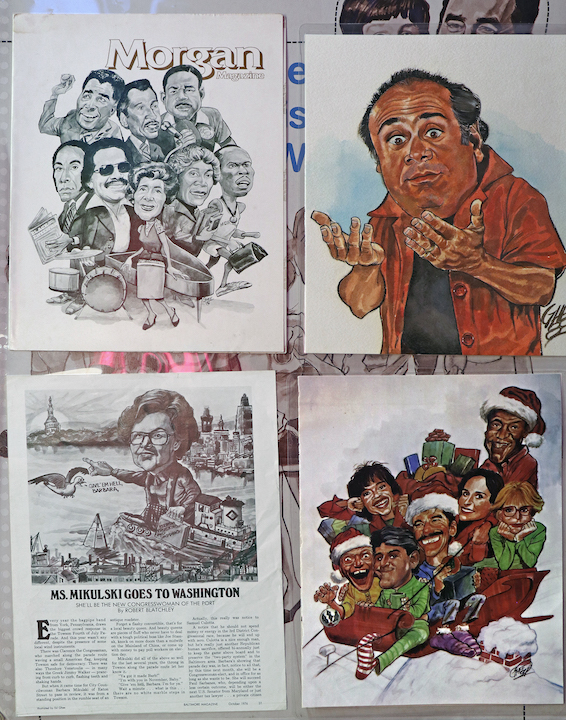

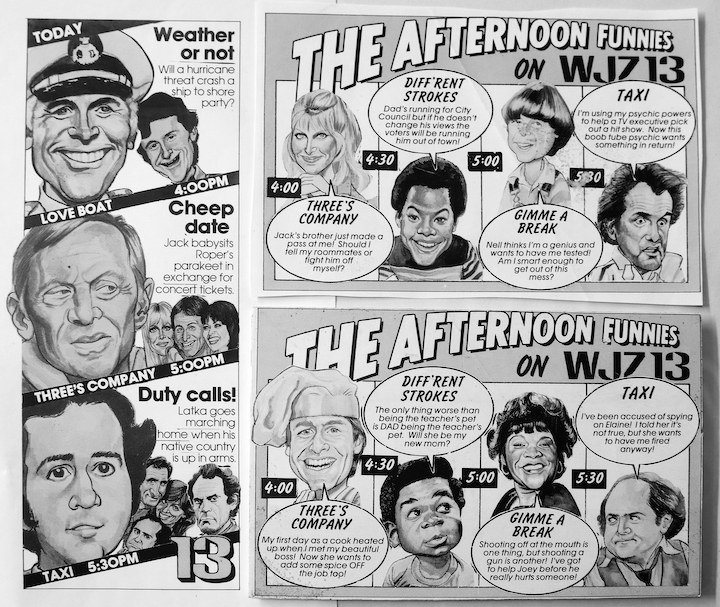

That chance encounter was the break he needed. After Doner, Ghee became an illustrator at WJZ-TV. (He likes to mention that he quit WJZ just a year before Oprah started there.) He eventually freelanced full time, drawing caricatures of Sugar Ray Leonard, Jerry Lewis, the Jeffersons, Michael Jackson, Radar from M*A*S*H, and so on, for clients and publications such as the Baltimore Jewish Times, the Baltimore Sun, and others. He also made good money drawing caricatures at the Inner Harbor for a few years in the early ’80s.

Around then, Ghee’s eyes started to cause him problems. He needed a cornea replacement and could hardly see, making his caricature work nearly impossible. He’s now had five cornea transplants, one in his left and four in his right eye, which has slowly rejected each one. A string of family members fell ill in the ’80s, too, and his career took a backseat as he became a caretaker with Cee Cee in their home. He didn’t stop making art, his approach merely shifted. With less visual acuity, he started painting bigger, releasing the need for tiny detail. He adapted his portraiture and caricature skills to a series of giddy, portly clay figures reminiscent of a jollier, less cynical Daumier. Ghee has painted eyes, scarabs, and spirals on cycling caps that he sells—the upturned brim of the one he wears every day features the Pan-African colors and red and white stripes separated by a big white star.

L: Illustrations by Ghee for various publications including Morgan State University Magazine & Baltimore Magazine, pen, ink, watercolor and acrylic (1976–1992) R: Ghee, “Baobab Tree,” acrylic on canvas (2018)

L: Ghee, “The Faces of Our Fathers,” acrylic on canvas (2019)

R: Illustrations by Ghee for Channel 13 (WJZ) from the late 1970s published in TV Guide

Early 1970s family portrait of Cee Cee, Ghee, Edward Ghee Jr., and Karen Ghee displayed in Ghee’s studio (courtesy of Ghee family)

Phylicia came into Ghee’s life in 1988. Her mother and her grandparents raised her, in Southeast Baltimore and Randallstown, respectively, and she spent more time with her grandparents in middle and high school. She attended the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology, where her art became more conceptual. Ghee drove her to and from school; Cee Cee remains, as Phylicia puts it, the glue of their family.

Phylicia never doubted that she would be an artist. In fact, there’s no separation between her art, her self, and her spirit as she uses photography, painting, performance, and ritual for healing and identifying the patterns, parallels, and spirals recurring in her life, work, and lineage. As a teen, Phylicia started to photo-document an ongoing series of ceremonial actions that connect her to ancestors, mark significant shifts in life, or help her find footing, often incorporating her body, movement, nature, and writing—something she attributes to her mother also being a writer. Her art has “never been a luxury,” Phylicia says. “It’s been always something that saved me.”

In a one-off collaboration, she and her grandfather set a bunch of charcoal briquettes on the ground in a spiral and lit them on fire. In the photo Phylicia took to document it, the charcoal spiral seen from above is spent, her bare feet and body’s shadow forming a kind of crown at the top of the image. “All these spirals started coming up, and then I realized that it’s subatomic, it’s galactic—a spiral on the earth, like a storm,” she says. The spiral has wound its way into her recent work.

In college, MICA professor Colette Veasey-Cullors asked Phylicia why the viewer doesn’t get to experience the processes her photographs document. Opening up her personal rituals for public viewing seemed too intense—those were for her own healing. She eventually tried out an iteration of what would become the Intrepid trilogy with her friend observing and documenting, and realized that she could share her work and still keep some of it just for her. “It’s almost like the work told me that I was going to be doing this in front of people,” she says.

Intrepid II, group ritual performance inside of “Breaking Open” installation (2015). Performed by Phylicia Ghee, Cheryl Ashley, Catrina Caldwell, Karene Bland, and Karla Benedict

Artist and curator Peter Bruun was drawn to Intrepid 0, and in 2015 asked Phylicia to be a “resident healing artist” for the New Day Campaign, a program fighting stigmas about substance use, recovery, and mental health. One evening, viewers gathered for Phylicia’s Intrepid I, part of a group show, First the Pain. In the middle of a large square of white paper, Phylicia sat still, eyes closed. White cloth waves spiraled toward video screens with tranquil imagery of water, stones, flora, and footage of the artist stuffing white cloth into her mouth and regurgitating it as a red spiral—an apt representation of processing pain that’s difficult to watch. Then, with a stick of charcoal, she began to move, writing in a circle around her body, which never left the paper, stretching and belly crawling to reach the edges, erasing as she continued writing, absorbing the words “I give thanks” on her skin and garments.

For Intrepid II, four women joined Phylicia in a diamond-shaped alignment, beginning with a similar contemplative stillness before they commenced their own writing spirals. As they wrote, speakers relayed candid storytelling from different voices about substance use, suicide attempts, soul-deadening jobs, and the need to take care and nurture. The charcoal’s looping and tapping rushed in like a tide, like an exhale. It’s a lot to sift through: Phylicia working through deeper self-knowledge and healing with four other women on their own paths. “It’s like when you cut yourself, and it starts to heal,” Phylicia says. “But that’s not a painless process.”

Phylicia dove deeper into her study and practice of African spirituality, more aware of her own capacious empathy. By the time she performed Intrepid III in 2018 at Martha’s Vineyard, she had been taking good care of herself, making time for stillness. Down to the black-and-white aerial footage documenting the piece, the third Intrepid feels more fluid and serene: Phylicia on the beach in the center of a paper square, spiral-writing the words “I am/ I surrender.” Along with rhythmic tides and breaths, the monologue soundtrack features reflections and whispered prayers: “This time was different. This time was lighter. I didn’t really know what it felt like to do this ritual without suffering, without grieving.” An altar with offerings and photos of her two great-grandmothers, Ghee’s mother and Cee’s mother, sinks into the sand. While watching, I can’t tell where the edge of the paper is underneath the sand, these materials melding. When she’s done writing, she sits up, coated with charcoal. She gets up and wades into the ocean, as if to cleanse.

Phylicia Ghee, Intrepid III, from Art on the Vine 2018, at Inkwell Beach, Martha’s Vineyard

(photo by Dayo Kosoko)

Among the cycles and spirals of Intrepid, Phylicia is working on letting go, reckoning with change and build-up and deterioration within art and life. “It’s a way of slowly etching into myself this peace with this impermanence, with the lack of control, and with things going away,” she says. As she circles around, erasing the charcoal with her movements, what’s left on the paper is a ghost text, faintly visible, because nothing fully goes away.

In the basement studio that Phylicia and her grandfather share, Ghee shows me a series of paintings that he’s working on now—dozens of small canvases with blue skies or warm sunsets and puffy clouds, with occasional treetops emerging from the bottom. He offers me a sky painting, and I pick a bright one with a strong, ominous shadow. The big skies are freeing. Painting them is a meditation. “I can do a cloud however I feel like doing it,” Ghee says. “I can design it however I want to, you know, without being overly detailed.”

Speaking to the two of them, I find myself trying to pinpoint and diagram this sense of resilience that radiates from their stories—what keeps Ghee going as an artist despite perpetual challenges? And how has Phylicia secured such a swirling synchronicity in her life, spirit, art, and mind? I hope for a logical, linear progression. How did you push through? Those are, of course, impossible questions. “I don’t know,” Ghee responds, tentatively, adding that as a kid he used to draw on newspapers, paper bags, whatever worked. “I mean, I just kept drawing,”

Phylicia persists: “Why did you keep drawing?”

This time, he’s more definitive. “It was my passion, it was in me,” Ghee says. “You know? It was in me, just like it was in you.”

Phylicia Ghee’s ancestor altar for great-grandmothers, from Intrepid III, from Art on the Vine 2018, at Inkwell Beach, Martha’s Vineyard (photo by Dayo Kosoko)

Phylicia Ghee‘s photographs of her grandfather, Edward Ghee, are included in a group show called In Conversation: Visual Meditations on Black Masculinity at the African American Museum of Philadelphia. The show, which features 55 women and nonbinary photographers of African descent, is up through March 1, 2020.

Photos by Kelvin Bulluck except where otherwise noted. Staff, jewelry, and adornments by Shannon Brown

This story appears in BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas Issue 08: Archive.