Last year, a group of Baltimore-based musicians and performers put on a benefit show for Moveable Feast at the 2640 Space—a live interpretation of The Band’s The Last Waltz, an iconic concert which had been filmed by Martin Scorsese. As soon as the band walked off the stage, attendees asked what they’d be doing next year. The question, which also served as a compliment, was surprising; the artists hadn’t really set out to make this a regular effort. But how do you come down from a performance high and ignore that kind of reception?

So this year, the 11-person production team (several also worked on the Moveable Feast benefit), are re-envisioning another canonical performance: Talking Heads’ Stop Making Sense, filmed in 1983 at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre by Jonathan Demme. For two nights at the Ottobar this weekend, November 16 and 17, more than 25 Baltimore musicians and performers offer their full-throated rendition of the Stop Making Sense concert. A portion of the profits will go to the Baltimore Harm Reduction Coalition, a community-based team that advocates—through education, workshops, and public policies—for safer practices for sex workers and people who use drugs.

The Last Waltz at 2640 Space in 2018 (photo courtesy of Human Being Productions)

There is an intriguing overlap in ethos among the production team, the beneficiary, the city’s multivalent DIY art scene, and the Talking Heads themselves. The production team is a loose network of artists who have worked together on other events (many who met via the Baltimore Rock Opera Society)—four producers; a sound engineer; and designers of the set, lighting, costumes, projections, print branding, and horn arrangements. While the team members lend their own flourishes to the spectacle, performers and musicians will showcase a variety of genres on stage all at once.

The BHRC’s on-the-ground labor fits right into that universe too. Music director Rich Kolm, whose day job is farm manager in West Baltimore, says he carries naloxone, the medicine that reverses opioid overdose and saves lives. He learned how to use it by taking a naloxone training through the BHRC. “I see the effects of this stuff literally every day,” he says. “It’s an issue that I feel we need to own as a community.”

And then Talking Heads, aside from their obvious hometown connection: “Their artistic style is very much like everything and the kitchen sink,” Kolm says. This principle helped them think through their rendition of the show. “You cannot be too on the nose for the show—you gotta dance with a lamp.”

Abby Becker, Rich Kolm, and Landis Expandis

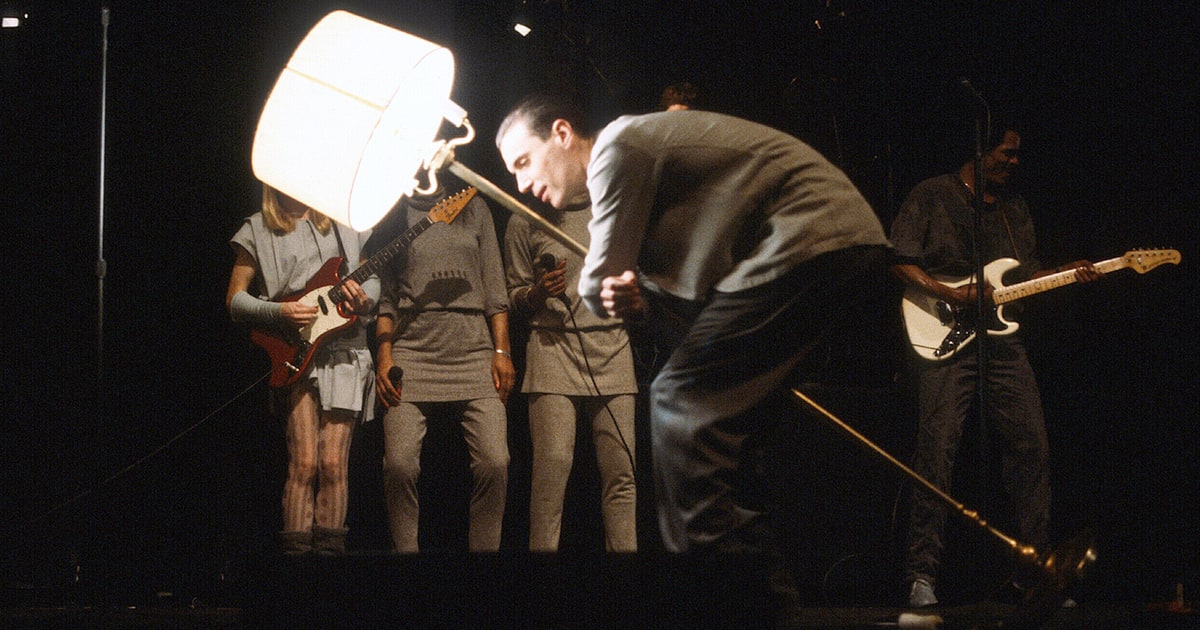

Stop Making Sense was not just a concert but also a piece of performance art. At the start of the filmed show, we see an enormous stage, empty except for some scaffolding around the back. “Hi, I’ve got a tape I want to play,” Byrne says, after he walks onstage wearing khakis and white keds, holding an acoustic guitar and setting down a boombox. A prerecorded beat booms out and leads him into an unusual solo rendition of “Psycho Killer.” His head bobs erratically, his eyes bulge. As the concert progresses, Byrne is joined by band members, one by one, while stagehands bring out mic stands and a drum kit and keys and occasionally swap out guitars, all noticeable but not intrusive.

Frontman David Byrne, who designed the show’s effects and choreography, has said he wanted to emulate “how a concert is made.” The film was a revolutionary concert film in its time, doing away with too many audience shots and documentary-like band lore and fetishistic close-ups of guitar strumming that pervade the genre. The cameras instead were largely pointed toward the stage from the audience’s perspective, and sometimes from backstage, making the movie-viewer part of the show too.

Abby Becker, one of the event’s main producers, notes parallels between the way Talking Heads was sort of a sponge for various musical styles and influences and the appealing expansiveness of Baltimore’s music scene. “They were art school kids who built a sort of funk band and hung out at CBGB’s with the punks,” Becker says. “The breadth of their influences make their music accessible to different kinds of people because they are completely untethered to genre.” In this production, an eight-person core band will play all the songs in order according to the Talking Heads’ original setlist, so, yes, you can expect to hear many of your faves, but the persons “playing” David Byrne will rotate. The Byrnes are an eclectic cast, including hip-hop artist Eze Jackson, Melissa Wimbish and Britt Olsen-Ecker of operatic pop band Outcalls, Sarah Danger of punk band Mallwalker, DJ/drummer Landis Expandis, celebrated actor Danielle Robinette, and many more.

The Ottobar’s stage is maybe 1/10th the size of the Pantages, so this version of Stop Making Sense won’t be a one-to-one reenactment in terms of sound, lighting, effects, and so on. That would seem a bit stiff, anyway. “There would be no point in getting all these artists involved if we weren’t having everyone put their own spin on the show,” Becker says. “There’s a very strong fidelity to the show, except that everything’s going to be different.”

David Byrne’s big suit (from Stop Making Sense)

The intentional range of style and genre among performers here is kind of a callback to the storied experimental and defiant shows Baltimore’s DIY scene has become known for. Changes within the scene, particularly the closing of DIY spaces over the past few years, have made such shows more challenging to execute, or even just to find. The licensed clubs and venues are vital for the scene’s stability, Kolm notes, but still, there’s something special about those basement and warehouse shows, where “it would always be like, one rock band, three rappers, some random guy bending circuits, and a DJ.”

“And then someone would do a set in the bathroom,” Becker adds.

With the diminished presence of those DIY spaces, lineups in general can seem a bit more rote and safe in those established venues. “We’re trying to silo-bust a little bit here,” Kolm says.

Siloing of the city’s art scene has long been an issue, and artists, organizers, and institutions seem more aware of it and more interested in changing it. It is way too easy to be complacent and let Baltimore City’s racial segregation and social stratification delineate the way we move through the art scenes. Pushing against this requires active, hard work, not passive ambivalence. And for those doing this, it is worth the effort.

“I look at it as part of my job, being a working artist in the city, to go out and go to shows and hear people that I haven’t heard before,” Becker says. “It’s our job to know each other.”

Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt, drummer Chris Frantz, David Byrne (from Stop Making Sense)

Show flier by Shannon Light-Hadley

Catch Stop Making Sense at the Ottobar on November 16 and 17. Tickets and info for the first night are here; for the second night, here. The shows will start at 9 p.m. (Saturday) and 8 p.m. (Sunday) sharp.