It took all of maybe 10 minutes into the version of “Cats, Criminals, & Comedians” that I saw Christine Ferrera perform at MICA a year or so ago before I was completely caught off guard by the work’s poignant combination of intelligence and humor. Subtitled “The Untold Herstory of Feminist Performance Art,” with it Ferrera becomes an art historian giving an enthusiastic PowerPoint lecture featuring a cast of fictional women performing artists that, nevertheless, accurately traces performance art’s history from mid-century to the present.

Her partner, musician and writer Dan Hanrahan, provides a soundtrack at different places in the piece, at times lending the lecture the faint comical whiff of a celebrated middlebrow documentary, at other times providing a sly, surreal musical commentary. Ferrera makes exquisite use of her Midwestern accent to speak with the approachable authority of an NPR host, and one of the first artists she mentions is a woman who moved to the United States from somewhere in Eastern Europe in the 1950s and created the first piece of endurance art by, as Ferrera savagely puts it, marrying a man she was indifferent to, having children she didn’t want, and suppressing her intelligence for the duration of her life.

Ferrera has showcased her flair for pragmatic absurdity in works such as “Starbux Diary” and “Google Art Video,” as well as in the stand-up comedy she’s been doing for about a decade now. She has a gift for taking something mundane and pulling at it until it becomes both comically rich and philosophically potent. “Starbux Diary” is as much about human intimacy in our alienated, postindustrial society as it is about the ridiculousness of asking a Starbucks Coffee customer relations department existential questions.

“Cats, Criminals, & Comedians” is an altogether more impressive feat. The roughly hour-long performance reaches Spalding Gray and Holly Hughes levels of inspired narrative, an invitation to reconsider what you think you know about women’s performance art. Mainstream culture has kinda always treated performance art, in general, as the even more ridiculous, esoteric, and fringe element of contemporary art, which is elitist enough as is. That attitude frames performance artists, especially women, as simplistic punchlines or radical extremists. And in “Cats,” Ferrera uses understatement and hyperbole to create a roster of fictional artists, whose works and lives recontextualize performance art’s history. Maybe it’s not these women whose art is extreme, off-putting, or just off, but the culture in which they live.

It’s a performance that involves a few visual aids, and Ferrera jokes that maybe all she’s doing is being a prop comic. “We’ve always sort of joked that I’m a maximalist, I’ll just keep adding and adding too much sometimes to a project,” she says during an interview at the Mercury Theater where “Cats, Criminals, & Comedians” runs from June 7 to 9 and June 14 to 16. “There’s this one Laurie Anderson monologue, ‘The Ugly One With the Jewels’ that I’ve never seen, only heard, but I aspire to get to that level of austerity and sophistication. It’s mostly just her talking. I’ve listened to it probably more than 100 times, and each time I cry during it, it’s such a good piece.”

She and Hanrahan sit in the Mercury surrounded by the set where they’ve been rehearsing with Jake Budenz, who is also performing in the piece with her. There’s a shelf with a number of items that, in some way, get alluded to or used during the lecture. “One of these days, I want to get to the point where it’s nothing but voice,” Ferrera says, and then sends her eyes around the room. “Obviously, I haven’t gotten there yet.”

Later this month, Ferrera and Hanrahan are moving to Chicago to be closer to their families. She’s lived in Baltimore for 12 years, Hanrahan seven, and their time in Baltimore has overlapped with a particularly dramatic arc in the local performing arts community. She moved to town when local performance and underground theater was blossoming. New DIY companies were forming, a grab bag of indie spaces provided options for trying out and seeing work, semi-annual festivals brought in emerging artists from around the country, and all of that was growing the local audience for experimental performance and theater.

Ferrera and Hanrahan are moving away following a fraught few years in local arts’ recent memory, due in large parts to the economic pressures of sustaining underground art endeavors in a rapidly gentrifying city, following an unrest that forced artists to confront the larger inequalities that get reproduced in the arts community, and when allegations of sexual assault and abuse within the scene starkly divided a small community into even smaller factions. This local arc bears mentioning here because many of the issues that women performance artists have tackled directly relate to and comment upon the forces, economic and cultural, that have riven Baltimore’s arts community. “Cats, Criminals, & Comedians” was in no way made in response to such events, but Ferrera developed it as she was living through this tumultuous time.

I caught up with Ferrera and Hanrahan to talk about feminist performance art, the terrifying rush of stand-up comedy, and internalizing misogyny.

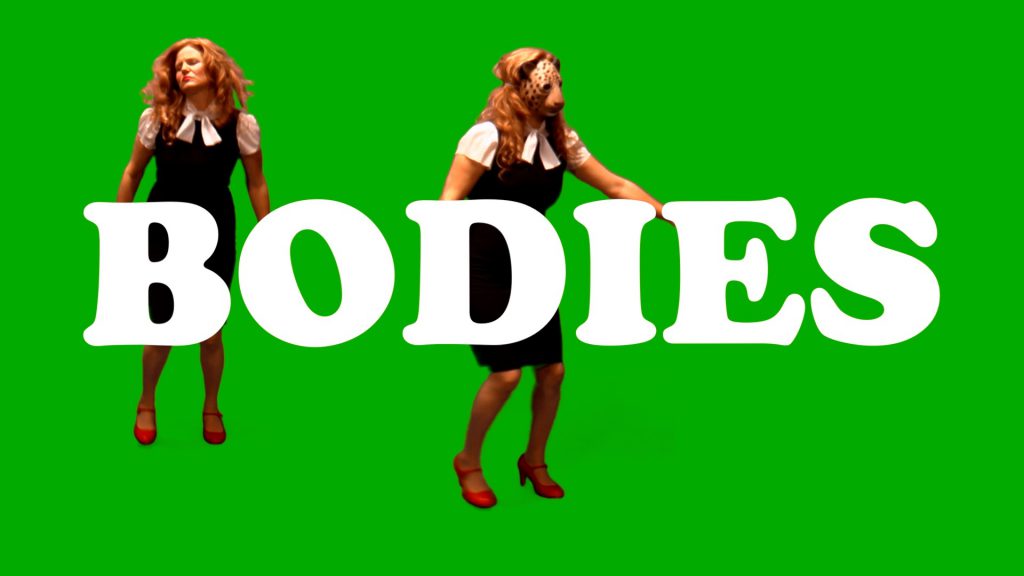

Cats, Criminals & Comedians Trailer from Christine Ferrera on Vimeo.

Bret McCabe: Tell me a little bit about the history of this piece specifically. And I ask because I guess the first time I saw you perform was in 2008 or 2009 at a Transmodern Festival, and over the years I’ve gathered that you tend to favor the monologue, and the lecture in “Cats” kind of works as a monologue with detours.

Christine Ferrera: This [project] started as my MFA thesis, and it’s changed a lot. I finished my MFA in intermedia art at UMBC in 2010 and my thesis was called “Funny Art Women.” It was about women who use humor in their art, generally performance artists. I wrote about my work in the context of artists like Miranda July, Dynasty Handbag, and a woman you might not have heard of but she’s a friend of mine, Oriana Fox, who’s really, really funny. We both do work about feminist performance art.

This was more of an academic paper?

CF: Yes. We had to write a written thesis and do work that accompanied it. The piece that I did for that was “Google Art Video,” which is two women discussing art in such a way that—one is sort of undermining the other. It’s an inner monologue divided into two voices, and in that piece I started introducing all these symbols of comedy: a banana, Groucho glasses, fake eyebrows, and other things referencing comedy. And—this is funny—my mom told me that my thesis was really good. She was like, “Oh, honey, this is such a good piece,” and told me that I should do something with it.

That’s literally how it turned into this piece. I thought, It’s insane to write 5,000 words about women trying to make performance art that is funny—I should actually make a performance. I took my thesis and started turning it into a PowerPoint art lecture. And that’s kind of where Dan came in and started peppering me with ideas.

Dan Hanrahan: When I lived on the south side of Milwaukee, which is a postindustrial neighborhood near Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River, I would walk through it every day home from work thinking, I want to do something with this neighborhood. I ended up inventing a history for all these locations there, and inventing characters who had invented experiences for a walking tour.

CF: I would talk to him about these different ideas about comedy and art and women and feminism. And he suggested making a character that represents each of those ideas, that it’d make it more fun and easier to explore the ideas. I think the first character I came up with was Katrina Vorkapich, who is modeled on Marina Abramovic. There’s about 13 artists in this lecture, and they’re each combinations of many artists. So anyone who’s a fan of feminist performance—if there are any, besides me—will definitely go, “Oh, that’s so and so and so and so.” Some of the characters are even informed by men.

DH: But they’re not satires. They’re not parodies of any specific people. One of the characters is a toil artist, and different feminist performance artists have worked with that concept. These aren’t like the Documentary Now series, where they parody documentary work and figures.

CF: About 15 or 20 years ago, I started getting more interested in performance as a medium because I had been painting for 10 or 15 years, which is very solitary. But I started feeling like I needed to switch it up, and I had this gut instinct that it was something performative or with film, something time-based. I took this class where we were studying performance art in general. And so much of it was so bleak, heavy handed, and masochistic—especially some of the very earliest, you know, like, Tehching Hsieh, also known as Sam Hsieh, a Taiwanese artist who did the “One Year Performances.” His stuff blows my mind in terms of using nothing but his body to make unbelievably powerful statements. But I also find it kind of dismal and bleak, because it’s literally like taking time off his life.

I started thinking about the concept of masochism, and why performance art was so much about masochism. That’s only one thing that you could work with. And I had some women friends that were doing performance art that were miserable. They were hurting themselves. I had a friend that wound up in the hospital. Why can’t you do endurance art that’s pleasurable and fun for a long time? Why is everybody always hurting themselves?

I thought a lot about masochism for this project, and [the artist-characters] in the early days of feminist performance art are working with forms of masochism. And then, as [the lecture] progresses, the artists start working toward taking power and demanding equality and power—and that, of course, introduces a whole other set of obstacles and problems.

When you were working on the thesis, was part of the reason you chose the three artists you picked to explore feminist performance art that wasn’t, well, pain-based?

CF: Yes. So much of [feminist performance art] involved hurting yourself. There were some women in my grad program that did end up really hurting themselves, and it really upset me.

I specifically chose Miranda July, Oriana Fox, and Dynasty Handbag because while being funny is maybe not their goal, they are interested in kind of having a laugh about certain things. Miranda July, I don’t pretend to know what her work is about, but to me, it’s about vulnerability. Dynasty Handbag is very funny about owning her insanity. And then Oriana Fox, her work to me is like a post-feminist critique of second-wave feminism.

And I wanted to know, Why am I so drawn to their art? And what am I trying to do in my early attempts at performance? I’ve always been interested in comedy and humor. And that interest segued into me doing stand-up comedy, which I really love. That came right out of that work right after grad school. I thought I should put my money where my mouth is and just get up and do it. I even took some stuff I had written as performance art and did it in comedy clubs. Some of it worked, some didn’t.

Let’s come back to the stand-up in a moment. In the process of researching feminist performance art and thinking about comedy, did you develop your own ideas about maybe why there was so much actual physical harm being done from, say, the 1960s into the ’90s?

CF: I think it all needed to happen. Those things needed to be made. I’ve heard a lot of debate about Yoko Ono’s “Cut Piece,” and not to get too into that, but some feminists like it; for some people it’s masochistic and making her a victim. To me, it was utterly necessary for her to do that piece. We do need to think about how we look at women’s bodies and how we just do what we want to women’s bodies.

I’m not a feminist scholar and I’m somewhat ashamed to admit that I haven’t read all of the feminist texts from second-wave feminism. But during a time before abortion was legal, or before there was even contraception widely available, you had to make bold statements.

Marina Abramovic, I love her work. It’s super powerful and totally necessary. She actually claims to not make feminist work, which is a whole other can of worms. But “Rhythm 0,” where there’s 72 objects and you can just do anything to her body with these objects, including a knife and a gun? That needed to be made, because the way culture was at the time, they had to say loud and clear, This is my body, it’s not your property, and it’s not an object.

The fact that anybody ever had to say that is heartbreaking. I totally respect it. It was totally necessary. But, for me, I remember when I was in art school a book came out around that time called Angry Women. And I hated that book, even though I never read it. Now, I would probably love it. But I hated the title, Angry Women. Why is making a statement about your body not being an object “angry”?

I didn’t like the label of anger. This is almost 30 years ago, you know? And I started thinking about why does it bother me that they would call any women “angry”? Or women who are feminists “angry”? In the ’80s and ’90s, militant feminists were even called “feminazis.” I think I got to this point where I felt that it’s not necessarily more powerful to be funny, but humor is a hugely powerful tool.

But there’s also this thing in the art world where if something is funny, then it’s not real art, it’s not serious. It’s been about 10 years since I’ve focused on comedy as an art form, and I still couldn’t tell you where that line is. To me, there is a difference, it’s just a very hard thing to articulate, about what makes something performance art as opposed to comedy.

Are you saying that people think that something funny cannot also be taken seriously?

CF: No. Audiences are the smartest, best barometers of what is funny or what is good art or what is true or interesting. I think audiences have almost perfect pitch when it comes to that. But I feel the art world still has certain notions about what is considered real art.

I know more and more performance artists who are, to me, doing genius-level work, but they’re mostly still working in DIY spaces because it’s not considered something that would be at, say, BAM or something like that. Some people are starting to, but it’s only been very recently.

In your own work, does the performance inform the stand-up or vice-versa? You say you can’t really draw a line between the two, but I’ve seen you do both, and there’s, of course, structural differences between a stand-up joke and a performance script, but your sense of humor is still your sense of humor.

CF: The performance 100 percent informs the stand-up because material-wise, almost everything comes out of the same place is the best way to put it. I write stand-up about things such as toxic masculinity and feminism and art. I write a lot of stand-up about art and conceptual things, as opposed to topical humor or political humor. Certain things that have almost become expected—like, everybody has a joke about Tinder or at least dating. I have one joke about dating and, of course, it’s not about that at all. It’s about low self-esteem. I approach writing comedy the same way I approach writing anything. But when I’m doing not stand-up, it’s hard to overcome the urge to want to do set up punchline, set up punchline. It’s hard to let things not be a laugh sometimes. I don’t do endurance work, I do narrative. I do stories. So they’re very parallel with each other.

Audiences are the smartest, best barometers of what is funny or what is good art or what is true or interesting. I think audiences have almost perfect pitch when it comes to that. But I feel the art world still has certain notions about what is considered real art.

Is one more comfortable for you than the other, or are they different aspects of what you do?

CF: Stand-up is really about the scariest thing to do. I’ve been doing it for a few years now, and I keep wondering, When do I overcome the fear part? Then I meet comedians that have been doing it for 20 years, and they’re like, Never. I’ve seen veteran comics backstage pacing and freaking out. So stand-up is always pretty terrifying. It’s just you and a microphone up there.

When I first was doing stand-up, I was comparing myself to all the other comedians. Now I don’t do that. I actually tell myself, I’m not here to do comedy. They think it’s a comedy festival, that we’re in a stand-up club. But I’m here to do some type of performance. They don’t know that, but I’m just doing some type of performance. I say that to myself. That helps me because if you’re so focused on doing comedy, you fall into the tropes and clichés of stand-up comedy really easily. You have to fight against that, I find.

I mean, you’re going to bomb sometimes. And now I have this thing where when it’s happening, I’m thinking, You’re going to bomb, and it’s OK. I want to be present with it as opposed to fighting it, which most comics do. They start getting combative. It’s not quite like asking, “Is this thing on?” but they will say something like, “I thought you guys were gonna like that one?”

That doesn’t work. Sometimes it’s just bomb time. Not too long ago, I got heckled by these three MAGA gentlemen, and there was no reasoning with them. I tried everything. I tried to bring them in. I tried to go back and forth. No, they were there to heckle and destroy, and that’s what they did. And I just had to suck it up.

In some ways, performance can be harder. When comedy’s going well, it’s the best thing ever. I’ve never done heroin, but I imagine comedy’s better. When people are laughing, there’s such an energy and it gets you going. Whereas with performance, usually people aren’t laughing or don’t react at all. You’re always wondering, Is this resonating with people? It’s hard to tell. For me, I like to be doing both, because I feel like one strengthens the other.

How has this piece has evolved? I mean, you graduated from UMBC in 2010, where you did your thesis at the intersection of women, performance, comedy, and feminism, and while you’re working on these subjects as an artist and a stand-up comedian, you’re also a person living during a time when those intersections are being more publicly and privately debated in this country—and in this city for that matter.

CF: When I first started writing and performing this piece in 2015, it was very different. It was originally just going to be a voiceover and a PowerPoint lecture. I’ve performed it only a handful of times, and about a year ago, we added Dan’s music. It’s been… interesting.

I mean, my modus operandi these days is to actually say what I’m feeling. The past few years have been some of the most difficult years of my life, and it’s only in the past few years that this piece turned into what it is. They were difficult for a number of reasons, but one of the main reasons was the breakdown in the performance community in Baltimore. Aside from a handful of open-mic comedy shows, this is the first piece I’ve done in Baltimore in two years, maybe longer. I can’t remember.

DH: The breakdown Chris is referring to was a direct result of a serial assaulter of women being put in a position of power and people siding with him or against him. That is, in fact, the wedge that split the community and put Chris in the position of not feeling comfortable in any number of spaces, because it became very apparent that the people from the art and performance and theater community who decided to side with the serial assaulter of women were very aggressive toward the people who didn’t.

CF: The reason that I, personally, got involved was because several women reached out to me. I didn’t have any experience with that before, where a woman reached out to you and tells you about their experiences. I didn’t know what to do. I met with different people and listened to them. To tell you the truth, I probably wouldn’t have ever known what to do if it weren’t for FORCE. Seeing their posters all over town that said, “I believe you”—that, literally, made me realize, “Oh, that’s what I should do. I should say, ‘I believe you, I’m listening, and I hear you.'” Because I don’t have any training. There’s no HR department for the arts community. I started listening a lot, and things got so ugly, so fast.

That time coincided with me being invited to go on a comedy tour. So I did. And I started touring and doing festivals out of town, and that’s mainly what I’ve been doing up until now. I would go out of town and have these amazing experiences in different cities. I would even to talk to people there about stuff, because a lot of people in comedy had gone through similar experiences.

Did going through that, having to think your way through a personal situation, inform this piece in any way? I ask because while I don’t think every comedian or performance artist or writer for that matter necessarily processes their own lives in their work, but one of the things I appreciate about both your stand-up and performance is your ability to take something innocuous and then make it intimate, and then take it someplace I didn’t expect it to go. So perhaps specific events didn’t make it into this piece, but I’m wondering if it encouraged you to say something with it that it wasn’t saying before?

CF: One theme of this piece is women undermining each other, I guess it’s called internalizing the patriarchy. I’ve thought so much about that because some of my biggest divides with that situation were from other women. And it was so painful. They’re women that I still respect and admire, that I know are feminists and artists.

This piece asks, why are women pitted against each other? Well, because you’re programmed that way by the patriarchy. You’re programmed to think there’s only a small space for women, so my best bet is to side with the patriarchy. The patriarchy works for me because I’m strong and powerful. And I don’t want to identify with weakness or victims. Oh, boy. So many women think, Victim? No. Bad. They don’t want to hear that word.

Personally, that situation was bringing up stuff I experienced in the ’90s when I was in my 20s and in a different art community and had my own painful things happen. And I was asking myself, Why is this bringing up 20 years’ worth of stuff? What I ended up understanding about myself was that I had internalized the patriarchy to the point where I thought, I’m not a victim. I don’t even like the word “victim.” And because I’m not a victim, this didn’t happen to me, and this didn’t happen to me, and this didn’t happen to me. I wanted so badly to be strong and powerful that I didn’t want to identify with victims. I wanted to be one of the tough ladies. And in between not identifying with powerful anger and being attracted to humor and vulnerability—because, to me, humor is all about vulnerability—somewhere in there I started realizing that I’m not a victim. I’m a survivor of many, many, many things.

I think I saw so much of that in other women [during this time] that it just broke my heart. If any of them were still speaking to me, I would have wanted to show them kindness, because that’s what I was seeing happening. You so don’t want to identify with victims and people—in this case, women—who have been hurt in that way because then you might have to reckon with some of your own pain.

Most of this idea of pitting women against each other was written into this piece already, though I didn’t know what it was called, internalizing the patriarchy or misogyny or whatever. This [divide in the performance community] crystallized it for me and made me really able to articulate it. Hopefully it even does it in a funny way, because it’s hugely important to me to illustrate how we internalize these things.

Have you gotten the piece to where you want it? I ask because—and this is just me taking a guess from reading your writings and seeing you perform—but I get the impression that you’re fairly particular about your language.

CF: I think so. I actually just rewrote the ending yesterday. I am kind of never satisfied. And one I’ve also been learning in recent years with performance and comedy is that a key part of it is not doing the fussy thing, which I’ve been doing for years. Instead of tweaking and tweaking and tweaking it, letting it live and trusting it a little bit more. And enjoying it, that’s a huge thing for me with comedy, it has to be enjoyable and I have to enjoy doing it. I have been working on those things. Let it alone and take some time to be intentional and look forward to it. So I feel really good about it. I’m working with Dan and Connor [Kizer] and Jake [Budenz], which feels like winning the lottery. Feeling supported is great, but working with people who get it and are funny in their own way is huge. But I’m still really nervous about it.

When and how did the music element come in? I guess the first time I this piece it had music, and it adds a nice surreal component to it, both soundtrack and commentary.

DH: I think I brought my guitar into the studio when she was working on it at the computer. I’ve composed a lot for theatre, and oftentimes I’ll hear a dialogue or monologue and some things start ringing in my head. And I said, This artist, doesn’t she kind of sound like this? We did a few of those, and Chris said, “I like how this sounds.” So we went through and starting working on the characters.

I know y’all are moving back to Chicago later in June for personal reasons. For good or ill, how has Baltimore, being a part of the arts communities here, informed your work?

CF: When I came here, I had never done anything beside painting and I had just started dabbling with video and performance. In grad school, I completely changed everything that I was doing. I started doing almost all performance stuff. I started doing comedy here, and wherever you start doing comedy has a huge effect on your life as a comedian.

For me, Baltimore’s been huge, because over the 12 years, it’s been unbelievably supportive, unbelievably experimental, unbelievably fun and kind, with so many brilliant artists. I lived in Milwaukee for 10 years, there’s not a big performance scene in Milwaukee. I don’t know if there still is now, but there was a vibrant performance scene here. There was a ton of performance when I moved here. And being able to go out and see performance and then get involved with it? I mean, I’m terrified to move because most of my work was made not just in Baltimore but kind of for Baltimore. I don’t know what it’s going to be like in Chicago.

Comedy, I’m not quite as worried because I have been traveling with it a lot. And comedy, of course, there’s a bigger circuit for that. Whereas I feel like the kind of performance that I’m interested in, DIY, experimental performance, there’s not that many cities where you can really do that.

We’re mostly moving to be closer to our families, and Dan lived in Chicago for 13 years before he came here. For me, Baltimore’s kinda been my whole world, so for me it feels like a heartbreak and kind of a huge, existential crisis. But like with every huge change I’ve made in my life, I have to trust that it’s the right thing. I mean, I’m going to be 50, that’s not the middle of your life, necessarily, but it certainly feels like a huge moment—especially as an artist, because you’re sort of thinking, Oh, you should give up now because you haven’t made it to the Guggenheim. I feel like I have to reinvent everything anyway, so I may as well just make it 10 times harder by moving.

DH: Baltimore’s effect on my art making and the development of my thinking and creativity has been very positive. I’ve made the acquaintance of several friend-collaborators who have exposed me to music and theater and ways of creating that I had not previously explored. People like Eyelashes (formerly Baggypantsrich) in songwriting and poetry, Temple Crocker in theater, and David Crandall in musical composition and arrangement, among many other people. Access to the experimental and free improvised music in Baltimore, even when the music is bad and when the scene itself can feel hermetic, is good for keeping the mind aware of sonic possibilities and of the value of spontaneity. As a writer, easy access to Normal’s, Atomic Books, Red Emma’s and now Bird In Hand is a wondrous thing and they are all within walking distance from our small house in Waverly.

What has been difficult for me as an artist living in Baltimore is being in my early 50s and finding that most art spaces and events are dominated by people much younger. Sometimes this is great for me and not at all a problem; other times it has sort of left me out. A dynamic about Baltimore that is tricky is that with all the colleges in the area, a group of people will graduate and be active as artists here for 5 to 10 years and then leave. That can have the effect of keeping things in kind of an immature state sometimes. That may have contributed to the very painful rupture that occurred in the DIY art/theater/performance scene. I got the impression that very unqualified people were tasked with dealing with a serious abuse scandal at their organization and were not up to the task.

“Cats, Criminals, & Comedians” runs at the Mercury Theater June 7–9 and June 14–16, at 8 p.m.

Images courtesy Chris Ferrera.