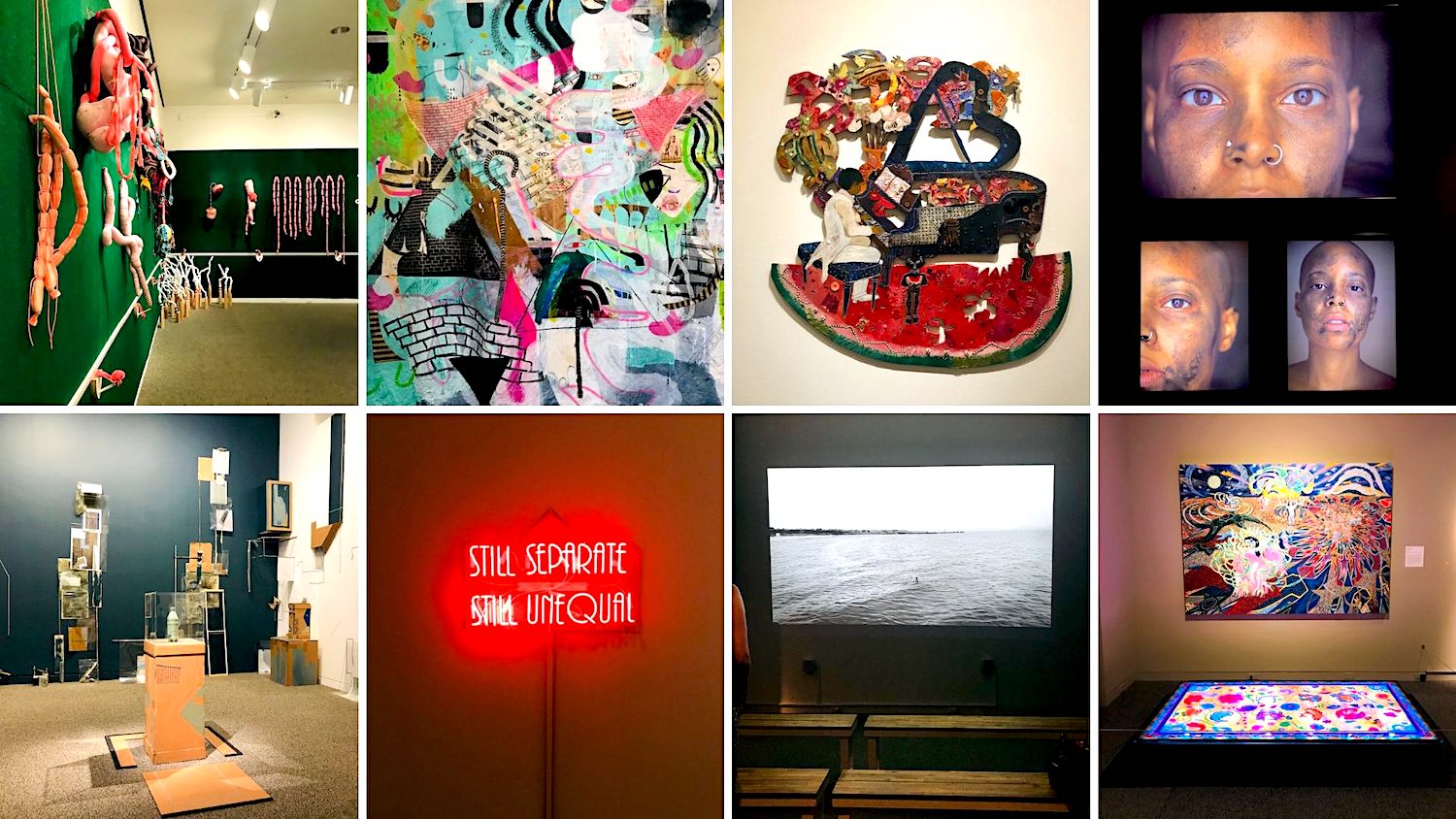

We are encouraged to see the art world, historically and currently dominated by white male artists, opening up to a much broader array of perspectives, especially here in Baltimore. This year, Sondheim jurors Laylah Ali, Regine Basha, and William Powhida selected seven well-deserving finalists to fill the galleries at the Walters Art Museum and, for the first time ever, women outnumber men six to one and all are, for lack of a better term, artists of color.

This doesn’t mean we are advocating for quotas in juried exhibitions or for jurors to select work based on anything but its excellence; however, it does make for a much more expansive vision with the potential to communicate well beyond the typical demographics of an exclusive art prize or museum exhibition. The result is that we are all offered a diverse cross-section of ideas and aesthetics, and a selection of artists who can collectively speak to significant global issues and current trends from an authentic personal standpoint.

In the 14th annual Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize, finalists Cheeny Celebrado-Royer, Jackie Milad, Negar Ahkami, Akea Brionne Brown, Phylicia Ghee, Schroeder Cherry, and Stephanie J. Williams collectively offer us a capacious view that can inform our thinking about history, race, immigration, migration, environmentalism, pop culture, and identity. This is a great gift to all of us.

Cheeny Celebrado-Royer

Growing up in the Philippines, Cheeny Celebrado-Royer experienced typhoons every other week and helped her family by “resourcing” available materials to patch the leaks in their home in between storms. The artist immigrated to the United States in her early teens, but her ability to realize the potential in humble and freely available materials has evolved into an art practice that aestheticizes a lean economy, offering striking moments of revolutionary and utilitarian beauty.

A single plastic bottle filled with gooey gray paint sits at the center of “Banal,” 2019, an installation of cardboard, nails, house paint, concrete, wood, tape, and plastic. Its placement at the center of the gallery under a glass vitrine further highlights its absurd power. Rendered as an art object, you notice its clean design, its approachability, the comfort it offers, and simultaneously its potential for destructive power, filling our oceans and landfills with tiny, toxic plastic bits that last thousands of years.

Additional objects are no less potent in this installation, whose title translates to “holy” in the artist’s native language, a resonant allegory for this work. Although the immersive environment initially seems spartan, offering only the natural colors of her art materials—studio trash, tape, cardboard—their purposeful composition and tight editing elevates and expands their innate qualities into a range of visual richness and understated metaphorical potential.

Unlike the tired “poetry of the everyday” trope employed by a multitude of young artists, where mundane elements are transformed with very little intervention into conceptual art, Celebrado-Royer does exactly the opposite and flips this lazy cliché on its head. She actually negates the “everyday-ness” of her materials, recognizing that each piece offers a unique history, tradition, and material culture. The artist isolates, highlights, contrasts, and composes her materials to highlight the complex innate story of each material, constructing a succinct and universal experience that illuminates the natural, nuanced evolution of design and beauty that will be required to survive our almost-certain dystopian future. (Cara Ober)

Jackie Milad

The prevalent stripes, triangles, rectangles, and loops within Jackie Milad’s larger works feel like they might lift themselves off the canvas when you’re not looking, hopping over to the other ones to acclimate to a new environment. In one piece, a few simple gestures like thick, black painted stripes read as a familiar and basic pattern, an emphatic, formal device meant to direct your focus like a map through dense foliage. In another, an even pattern of black and gold stripes take on larger cultural significance, along with the imprecise and inverted pyramids, triangle-voids, rectangle-bricks, glowering eyes, and winding snakes abounding in Milad’s surfaces.

That marks and symbols could have a life of their own—that their meanings are always debatable, depending on variables like viewer and context—is what Milad is getting at in these large, visually complicated works. Disrupting the expectation of an artist’s precious archive, Milad selects parts of her own previous works to collage into new ones, drawing and painting over them, reassigning the meaning and value of “finished” pieces. This way of working adds another layer to Milad’s continuously recombinant exploration of her identity, especially of her Egyptian and Honduran heritage, giving herself freedom to invent an ever-evolving personal language, archive, and symbology.

The resulting works, big enough to get lost in momentarily, feel alive and inscrutable as a whole, which is just fine and good and healthy, because once you think you know something, you project all your shit onto it. Milad also injects a few warning cues about that to viewers. In “Eres Mucho,” a “fuck you” middle finger turns into a slinky snake; in “Chaos Eyes,” an angry clash of brush strokes spell out “FUCK IT”—these could be read as frustrated refusals to be located, named, catalogued, isolated. The only things that seem set firmly in place within these unhemmed and unstretched canvases are their edges, stringy and frayed as they are, but coagulated with a gold-painted “frame” which will keep them from unraveling, for a little while at least. (Rebekah Kirkman)

Negar Ahkami

“After Winter Must Come Spring” is a magic carpet meets 1970s disco. The blinking dance floor glows with different colored lights, projected through a glass surface embellished with the abstract garden patterns of a Persian rug. Negar Ahkami typically works in painting, clay, and mosaic, but created her own riff on magic carpets to “celebrate the universal desire for escape.” The Iranian-American artist made the piece during the height of the Muslim Ban rhetoric in the US, and wanted to show respect to the cultural contributions of her ancestors while placing them into a secular and utilitarian context. Although the floor has been danced upon as intended in other iterations, at the Walters it is cordoned off as a visual object, an empty stage desperately longing for multi-generational karaoke. It animates the painting that hangs above it, bathing it in a progression of blinking rainbow hues, but it also stands out from the rest of the artist’s work on display, claiming the lion’s share of a viewer’s attention like an overzealous wedding guest twerking while everyone else is doing the electric slide.

Ahkami is a Virginia-based painter and sculptor whose work is informed by her immigration from Iran at a young age, specifically the cultural turmoil and contrasting layers of information she attempted to integrate as a child, unsuccessfully aligning her own memories of Iran with US propaganda. A sense of fracture and contrast animates the surface of her two-dimensional works which often resemble mosaics with bits of ceramic tile slathered together and images superimposed or embedded that resemble familiar folk-art fantasy women, goddesses, or mermaids. They don’t completely hold together, with the image fighting against the fissured surface, but this is consistent with the artist’s concept: living simultaneously in two separate worlds, never able to reconcile two separate childhoods. The series of paintings on display at the Walters illustrates this uncomfortable process.

Like the twinkling dance floor, “The Taking” is another anomalous piece that includes painted ceramic fragments assembled on a rectangular surface resembling a bulletin board. The pieces function like clues or faux artifacts from the future that include images of architectural patterns and pop culture to tell a new and jumbled version of present-day history. Unfortunately, it includes a caricature of Donald Trump, red tie and all. His presence contemporizes the piece but also hijacks it; he is an unwelcome distraction in an otherwise gentle mystery. (CO)

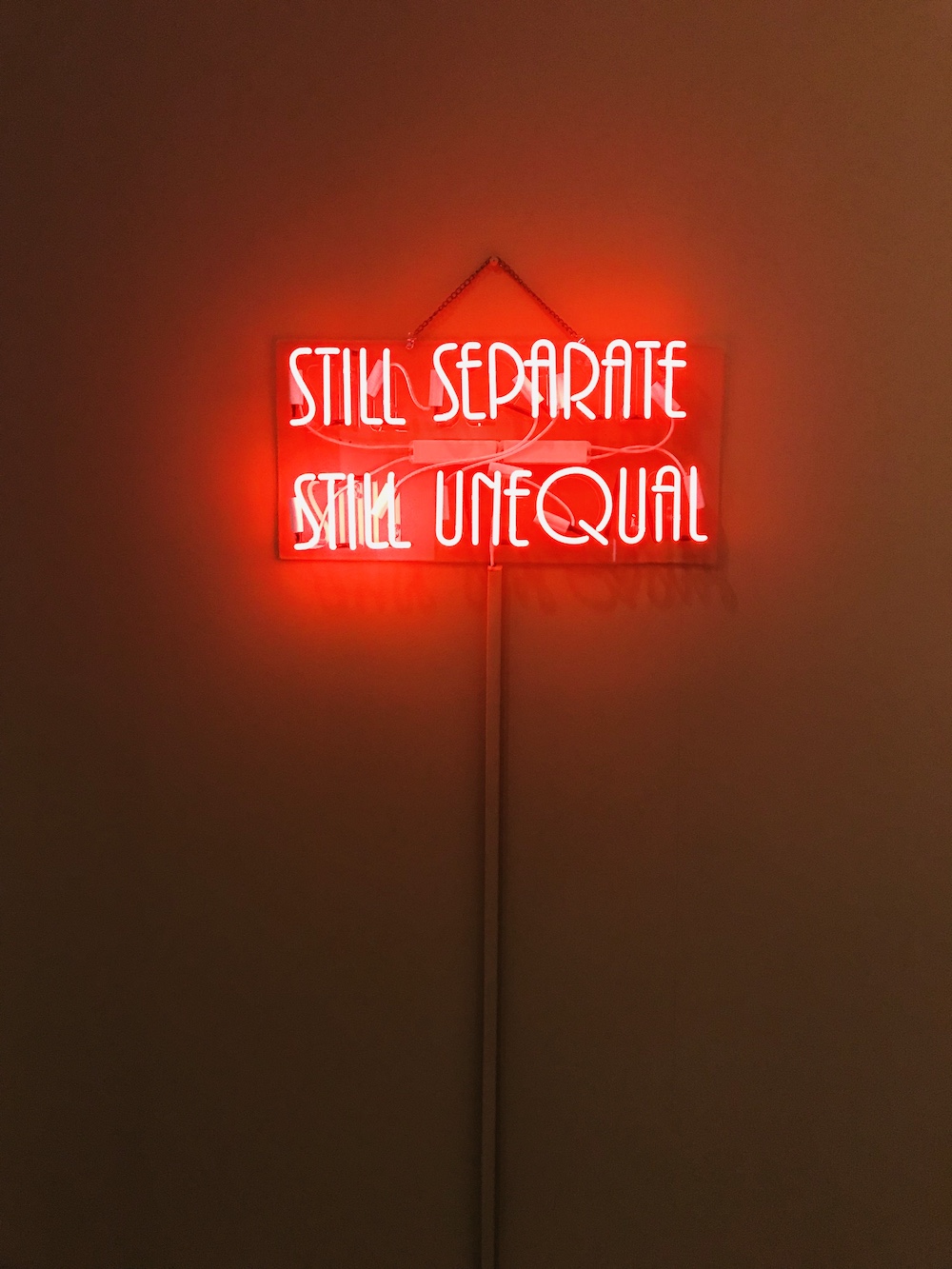

Akea Brionne Brown

One ongoing, multi-part work by Akea Brionne Brown, “Black Picket Fences,” takes up the artist’s whole gallery space in an expansive and research-heavy photographic installation. A series of photos of suburban homes and Black folks in their homes, interspersed with archival material like pages from a 1948 illustrated report on Washington, DC-area segregation, cumulatively offer a view into the everyday and the environmental and economic impact of racist urban planning and policy.

Driving home the fact that little has changed to right our past wrongs, on that same wall appears “This Is America,” a faux-newspaper with a headline lifted from the HuffPost about Delegate Mary Lisanti’s racist remark about PG County (“Maryland Lawmaker Apologizes For Calling Majority-Black County A ‘N****r District’”) from February; sidebar headlines flesh out this American portrait, with a focus on the precarity of the Black middle class: “Facebook (Still) Letting Housing Advertisers Exclude Users by Race”; “How Black Middle-Class Kids Become Poor Adults”; “A Black Man Was in His Building’s Lobby. A White Neighbor Accused Him of Not Living There,” etc. This newspaper functions as a syllabus for understanding Brown’s work as well as the communities we occupy generally. Brown’s photo of a room empty except for reflective surfaces like mirrors, metals, and glass, reads like a prompt for self-examination.

Much of the imagery here shows more than it tells, especially the shots of ordinary houses and candid portraits of people in private spaces. Some elements of Brown’s installation seem like seeds for further exploration, like the printed and annotated Urban Dictionary definitions of the term “oreo”—but perhaps that’s because understanding and rectifying race and class divisions in this country (and their effects on our identities) is never-ending work. These images, photos, and notes could unfold exponentially in a larger space.

A few very sweet images beam among the heavy analysis and may propel viewers toward more urgent engagement, like the photograph of three young children crowding against a window, looking outside. Reflected on the window glass are power lines and buildings surrounding their home, and if you catch this photo at just the right angle, Brown’s red neon spelling out “STILL SEPARATE STILL UNEQUAL” reflects off of the kids’ bodies, too. (RK)

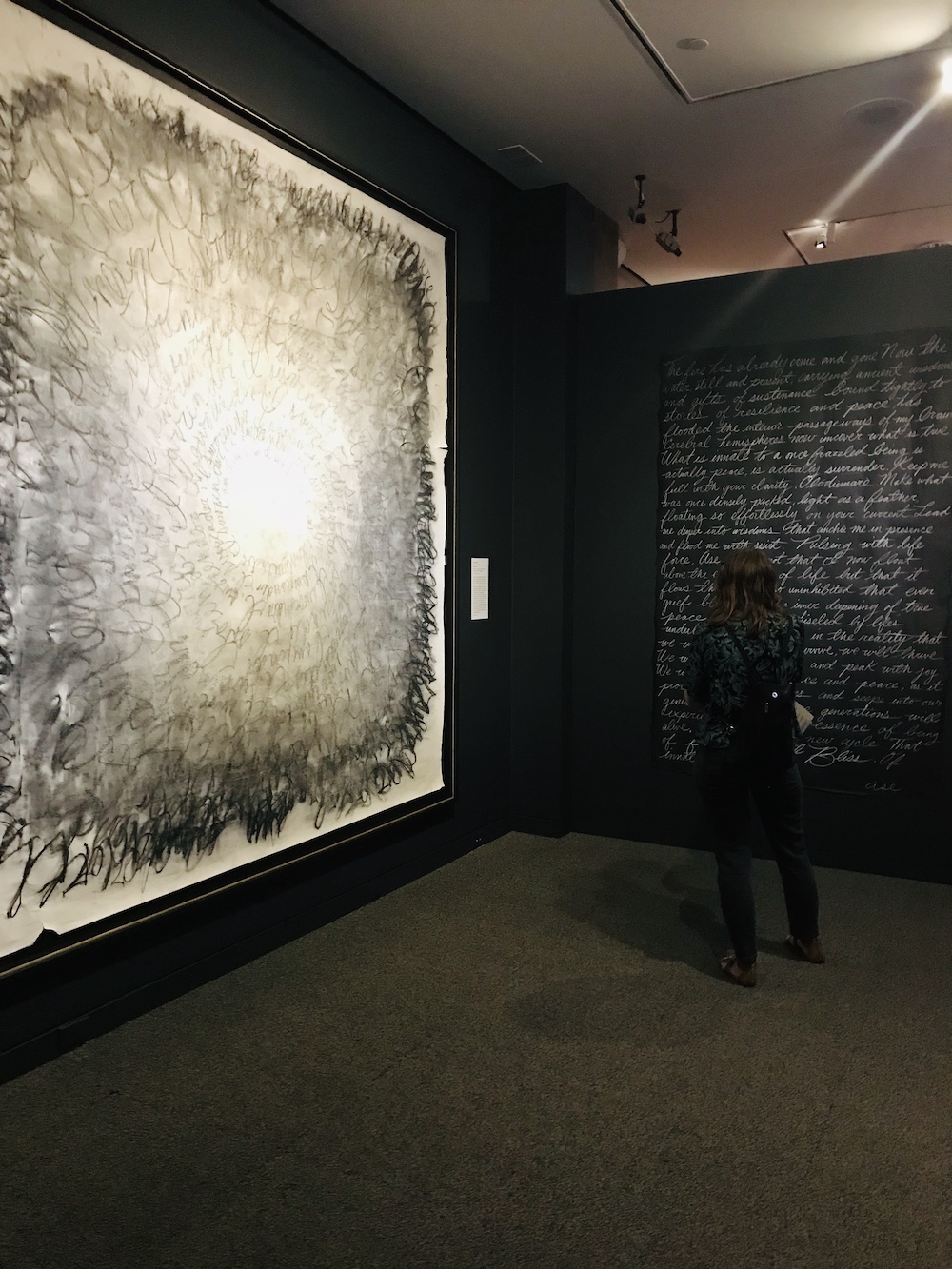

Phylicia Ghee

Phylicia Ghee understands the drama of black and white. On walls painted black to offset the white surfaces and text within her work, the artist has focused on a handful of large pieces which are remnants and documentation of past performances.

The main attraction in the space is a large video projection playing most notably a performance titled “Intrepid II,” which the artist completed in late 2015 at Area 405 when she was the Resident Healing Artist for the New Day Campaign. In the performance, Ghee and four other women (three of whom were in recovery for addiction at Powell Recovery Center) kneel on 9’x9’ squares of white paper, wearing white undergarments, and turning first on their knees and progressing to their stomachs as they write around themselves in charcoal, a favored medium of the artist. One of the resulting drawings from this performance hangs opposite the projection in a massive frame reminiscent of the scale of history painting.

While essential to the maker as mantra and affirmation, the once legible written words of the work have been largely obliterated by the repetition of writing and rubbing, the end result looking like a close-cropped picture of a gray flower with a white center created by the author’s knees. According to the artist’s website, these shapes are meant to be spirals which for the artist and her grandfather, an important teacher and influence upon her work, are a symbol for expansion, transformation and evolution over the challenges of life.

Displayed on the wall of a museum instead of the floor of the industrial space where it was made, this work feels static, but that’s a drawback inherent to performance work: despite video and photo documentation and ephemera, there are still gaps. However, the care and consideration put into the display and arrangement of the space allows outsiders to appreciate the inherent beauty of this work. It is this strength of the contrasts within the black-and-white drawing and video documentation that has been the lingering taste of this show for me, days later. (Suzy Kopf)

Schroeder Cherry

Every profile on Schroeder Cherry will tell you he’s a former museum administrator from Washington, DC, whose background as a puppet maker and painter inspires his current works on panel and found furniture. But what typically gets left out of these biographical accounts is an appreciation of the work itself, which is as unique as it is skillful.

Mixed media is being widely spotlighted in long term museum solo shows with notable artists like Mickalene Thomas (commissioned to take over the BMA’s East Lobby this fall) and Mark Bradford (whose work “Pickett’s Charge” is up on an entire floor of Hirshhorn in Washington, DC through 2021) combining elements of adornment and traditional fine art media to challenge our preconceived notions of race, class, and gender. Cherry is doing a little of that himself by using physical signifiers of Black culture and trade such as dominos, shells, beads, playing cards, cut-up frames, and locks with keys, as well as focusing a series of works on a traditionally Black space of community and commerce: the barber shop. By using the tangible materials of these spaces and combining them with the traditional fine art media of painting, Cherry gives his audience a tactile element that roots the work in reality.

But beyond this, these works are expertly made, their many pieces fitting tightly together in a manner that feels not only deliberate, but as if the many parts were indeed always one. The painted elements cohere with their 3-D counterparts, settling into a visual harmony that checks a lot of boxes—skilled painting, historical connection to craft and folk traditions, utilization of both handicraft and machinery (Cherry uses a jigsaw to cut many of the wood parts).

Individually these works are complete on their own and would be a welcome addition to any collection. The issue here, in a museum solo show, is that there is a certain sameness to the gestures, the repetition of elements and combinations that begins to feel stale as one progresses down the wall of works, of which there are probably too many installed. Still, it is pleasurable to spend time with the pieces one on one, studying their components which are like a puzzle, many pieces making up a whole. (SK)

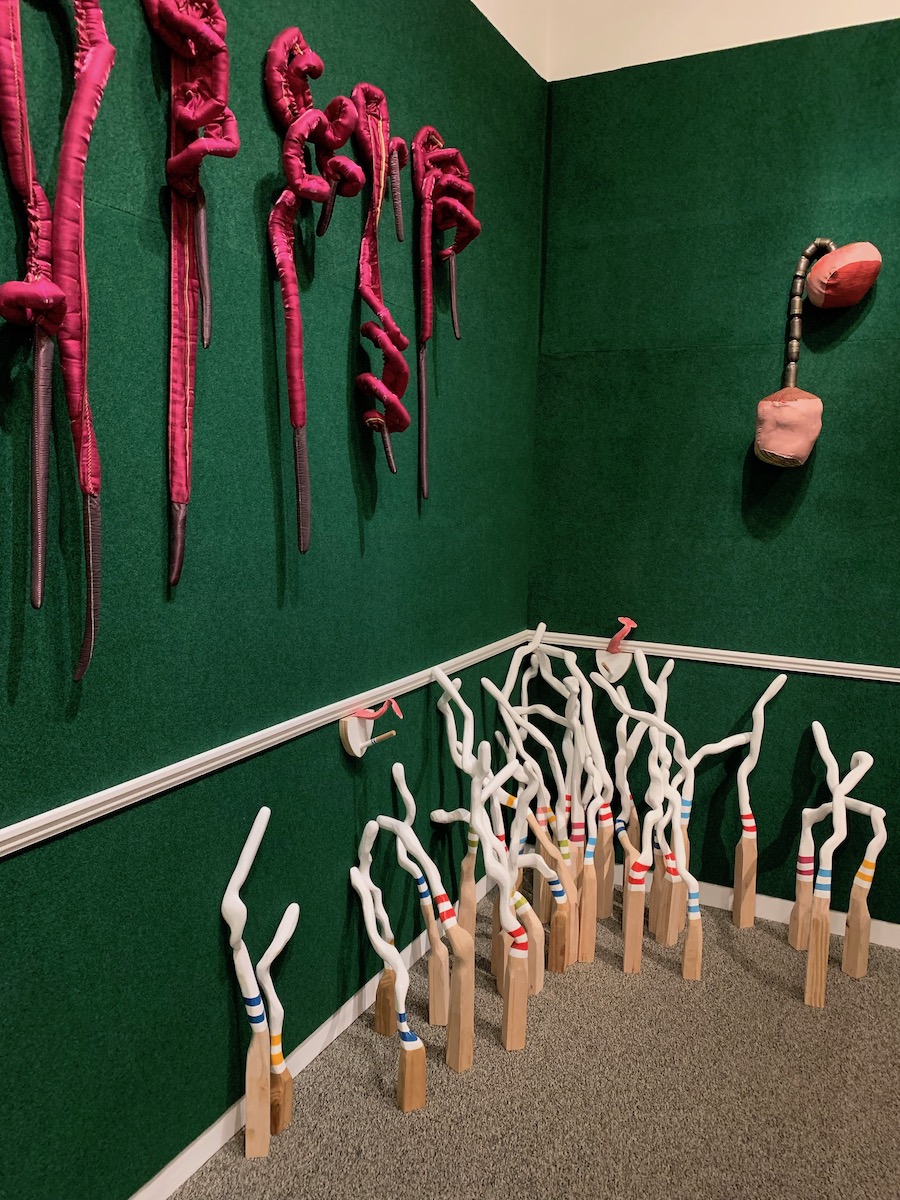

Stephanie Williams

Ropes of sanguine pink sausages cascade down a fuzzy green Astroturf wall in the final Sondheim finalist exhibition space. Stephanie Williams’s sculptures capture Americans’ fraught relationship with food, specifically with meat, eating, and their own bodies with larger implications upon the way Americans define themselves. In this installation, the sculptures hang fleshy paper chains, assorted reds and pinks contrast mightily with the green backdrop, and for me, they conjure up the fantasy of farm animals munching happily in green pastures before being slaughtered and ground up into sausage and larger questions about how larger narratives swallow up marginalized ones.

Taken as a whole, Williams’s sculptures satirize the human ability to transform carnage into comfortable, sanitized packages and to simplify that which is incredibly complex. I’m not judging anyone’s eating habits per se, but our need for discreet “food language” (such as the term burger or steak instead of say, dead cow) reflects our discomfort with death, and our collective desire to associate our food solely with supermarkets instead of slaughter. This refusal to accept the reality of how the sausage is made leads to callous, irresponsible decisions around the ethical treatment of animals, environmental waste, sustainability, and our impact upon all the living things on our planet.

Other corporeal associations abound in Williams’s work, on a small video screen displaying her beautiful stop-motion animation, where balut (a fertilized fermented duck embryo, boiled and eaten from the shell, traditionally as Filipino street food) engages with stereotypical food from marginalized communities like Aunt Jemima syrup and Uncle Ben’s Rice. Using food as a metaphor, all of Williams’ work reflects the artist’s heritage and family history, contrasting American history learned in school with the stories passed down from family members. Regardless of medium, Williams offers macabre and humorous observations about human bodies, meat, food, and the way the names we assign to all aspects of our lives build contrasting hierarchies of taste. At the Walters, Williams offers a Muppets-meet-Manson aesthetic that reminds us that we are all made of flesh, blood, and sinew, just like the animals some of us choose to eat and that we have choices in the way that we engage with the complexity of history, identity, and bodies.

Gently, Williams deadpans the tendencies of humans, neither savoring the carnage nor condemning it. Rather, her work questions us earnestly: What kind of an animal are you? What kind of an animal do you want to be? It serves as a reminder that when we hide behind sanitized terms like “fillet mignon” or “veal” and neat plastic packages where the smell of fear and blood has been erased, we are no better than the supposedly “dumb” animals we consume as food. (CO)

Photos by Mariá Sanchez and Cara Ober, with a few images sourced from artists’ websites.

The finalists’ exhibition is on view Saturday, June 15–Sunday, August 11, 2019 at the Walters Art Museum, located at 600 N. Charles St. An award ceremony and reception takes place Saturday, July 13, 2019 at 7 pm at the Walters. Galleries open at 10am. Admission to the exhibition and opening reception are free. Each finalist not selected for the prize is presented with an M&T Bank Finalist Award of $2,500. The 2019 jurors are Laylah Ali, Regine Basha, and William Powhida.

Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize Timeline:

Finalist Exhibition: Saturday, June 15–Sunday, August 11, 2019

Award Announcement: Saturday, July 13, 2019 at 7 pm / Galleries open at 10am

Artscape: Friday, July 19–Saturday, July 21, 2019