Mark Bradford’s Tomorrow is Another Day Part II at the Baltimore Museum of Art by Cara Ober

In real estate and contemporary art, the impact of context cannot be overstated. In the right neighborhood, a rickety dump with a bad roof and a 1970s kitchen can garner a million dollar price tag, and in a less desirable area, the same house will sit, unoccupied, indefinitely. Artisanal bathroom tile with radiant floor heating can only get you so far; their impact upon home value is inconsequential compared to location and the whims of a volatile real estate market.

Although we often think of art in a vacuum, the impact of environment actually plays a huge part in its success or failure. In a global art world, it is customary for museum exhibitions to travel, but site-specific work, made for a particular place and time, does not always translate effectively in a new setting. This explains why Mark Bradford’s Tomorrow is Another Day, conceived and executed for the United States Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale but now at the Baltimore Museum of Art, is essentially the same show as the original, but only musters a fraction of the energy.

I raved about Bradford’s Venice pavilion last May for Hyperallergic, but it was impossible not to compare the wild and maximal aspects of the biennale exhibition to the BMA’s new, sanitized version. I am left wondering if the attempt to translate site-specific artwork from one place and time to another was a well-intended oversight or if Baltimore, as a distinct context for the work, was not seriously considered because the curators knew that most of its audience didn’t see the original iteration in Venice.

The first Tomorrow is Another Day opened in May 2017, representing a United States seething and divided over the inauguration of Donald Trump. This national strife and its global reaction animated Bradford’s exhibition, which was amplified exponentially by its official US platform on an international stage.

Photo of the author, taking photos of of intentionally placed trash outside the

Photo of the author, taking photos of of intentionally placed trash outside the

US Pavillion in Venice in May, 2017

In Venice, it meant something when Bradford piled trash and rubble in front of the US pavilion, a building designed to magnify American power and ingenuity. It was particularly meaningful that the interior dome was blacked out with tarred paper and functioned like the bowels of a slave ship. In Venice, the historic pavilion, modeled after Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello home, lent power to Bradford’s work-as-protest there; the paintings, installations, and video worked in tandem with its context to provoke outrage and much needed critique. In Venice, it was evocative to be forced to enter the pavilion by the side door and not the front, mimicking the role of enslaved people (including Jefferson’s own children) at Monticello, a physical metaphor for the “separate but equal” race-baiting campaign that Trump had just successfully implemented.

With the migration of site from Venice to Baltimore, from international to regional, and almost two years into a Trump presidency, the intensity of Bradford’s Tomorrow is Another Day has also migrated. As in the Biennale, Bradford’s large paintings are muscular and the diseased-looking “Spoiled Foot” installation forms a compelling and combative introduction to the show. However, the thrill of an international, politically charged context in Venice lent purpose and energy to the original exhibit, which could and should have been replaced–with new works based on research specific to Baltimore, like a new installation to compensate for “Oracle,” installed under the pavilion’s dome and not included at the BMA, or even the addition of an older Bradford video like “Practice” (2003) where he plays basketball wearing a 4-foot hoop skirt.

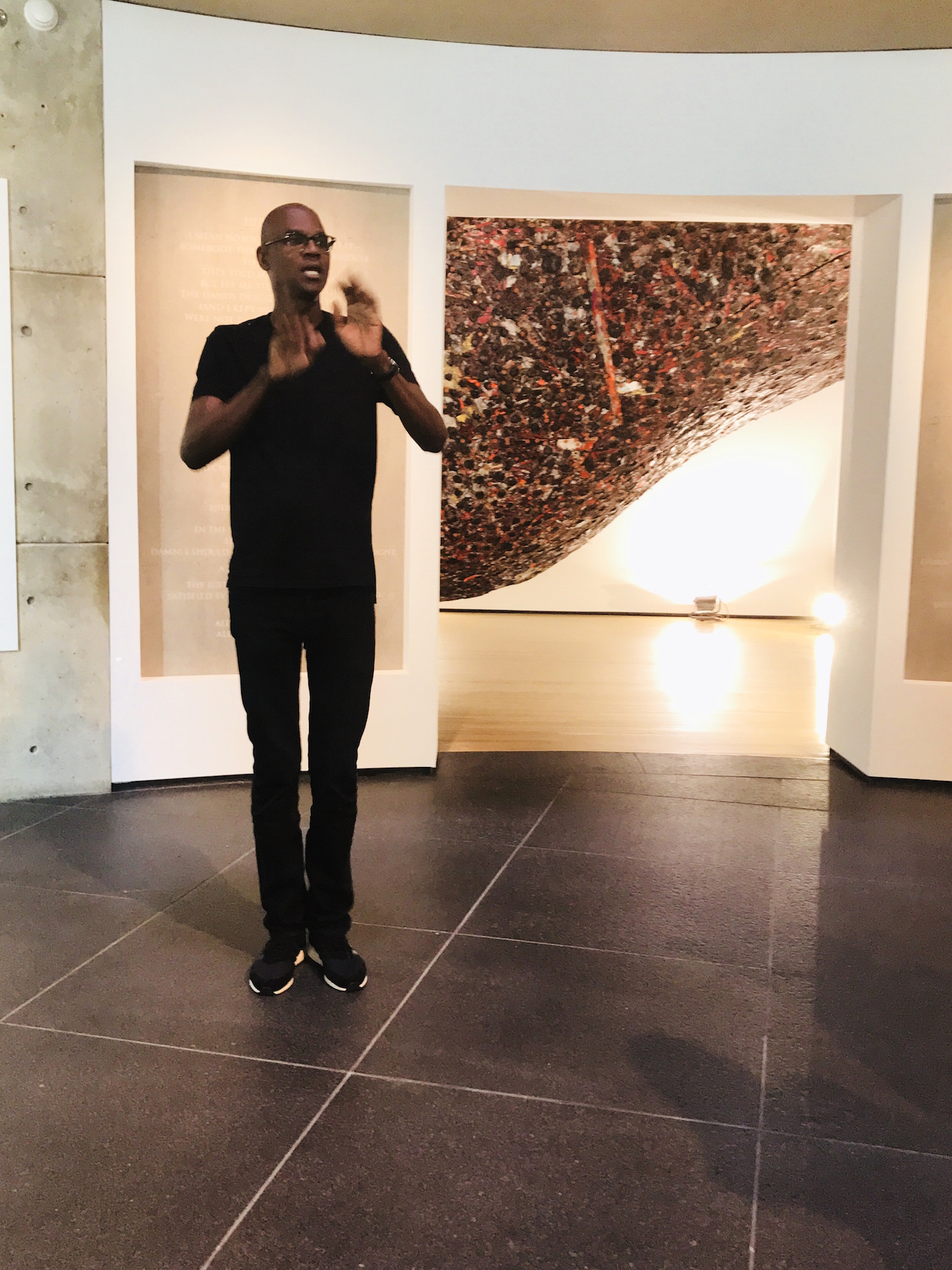

I asked Bradford about his approach to site-specificity in Baltimore at the BMA press preview; he said that this time he didn’t want to make any “last minute” works–as he did in Venice. Bradford said that the work’s new site-specific appeal hinged upon his background as an urban black artist now showing in a majority black city, suggesting that his abstract exploration of race and identity would translate differently, but no less effectively, to a Baltimore audience, rather than a primarily white international audience in Venice.

I let it drop after that, feeling vaguely disappointed, but I will admit that I could listen to Bradford talk all day long. He is charming, self-depreciating, and easy to love; his cult-of-personality status lends contagious vitality to his work when he is present. During Vernissage week in Venice, I was impressed that the artist chose to play host in the pavilion for most of the week, to conduct tour after tour with museum groups as well as the general public. However, after writing a glowing review of the show, I was left with lingering doubts about the primary function of the work vs. the artist’s personable and hands-on relationship with it, wondering if what I had actually witnessed was performance art, with the artwork functioning as props for a global Bradford brand.

In person, the artist offers a unique candor, authentically earned by his physical stature as a 6 foot 7 inch tall black gay man in America, of never having the luxury of blending into any room he has ever occupied. Bradford embodies his otherness like a champion; he makes it inclusive and universal, nurturing kindred outsiders like the art activist guru savior we’ve all been waiting for. He makes his global success seem attainable; you, too, can transform your own humble beginnings into the pinnacle of high art if you ask yourself the most difficult questions and own the answers in your work.

Bradford has the ability to make you feel included in his American struggle and subsequent triumph through his abstract works. He possesses a natural timing, conversationally but also strategically in his career, with the effectiveness of his political exhibition in the biennale as a primary example. In 2017’s Venice, a prevailing sense of disaster, of sourness and gloom and frustration, of the deflation of the ideals of the American democracy were all ripe for the plucking and, especially in his two installation based works in Venice, “Spoiled Foot” and “Oracle,” Bradford challenged all that was wrong with America on a global stage and it came off as a heroic gesture.

Bradford in front of “Spoiled Foot” at the BMA, L, and BmoreArt’s Alex Oehmke enjoying the installation in the gallery

“Spoiled Foot” is successfully recreated in a similar fashion in Baltimore, serving as your entrance to the exhibit and sets expectations high. This is what I wrote about it for Hyperallergic last May:

Inside, claustrophobia kicks in quickly with “Spoiled Foot,” an intimidating, site-specific behemoth. Suspended from the ceiling like a dead whale, the piece dominates the darkened gallery, forcing you to scuttle along the periphery. Comprised of collaged paper, trash, metal grommets, and orange roofing tile, the piece is shellacked together into a bulging, seething mass that impinges upon your personal space — that precious American concept — and forces you closer to your neighbors than is customary. This imbalance — between the sculpture and its audience, scale and space, light and dark — is also an apt metaphor for the way Bradford, who’s African American and 6 foot 7, has always had to negotiate a world seemingly made for smaller, lighter-skinned people.

At the BMA, “Spoiled Foot” is visible through a dramatic entrance arch into the Contemporary Wing, and the space, formerly the Front Room gallery, has been altered so that you must confront and circumvent this object to enter the exhibit. For some, the experience can be giddily joyful and for others it is threatening; either way it provokes a powerful reaction. Installed in Baltimore, the dark closeness of “Spoiled Foot,” abruptly transitions, and you find yourself blinking in bright light bouncing off lofty white walls. The rest of Tomorrow is set up like a traditional exhibit in two large galleries, while the other half of the museum’s contemporary wing, and its vast collection of modern and contemporary masters, is walled off as a temporary storage space with no access, a colossal and awkward distraction if you’re familiar with the institution.

“Medusa,” 2016-18 and “Thelxiepeia,” 2016 at the BMA

“Medusa,” 2016-18 and “Thelxiepeia,” 2016 at the BMA

The first gallery features three giant bruise-colored paintings named after Greek sirens with “Medusa,” a large, flame-shaped sculpture in the middle of roiling, tarred paper, referencing the famous gorgon with snakes for hair. According to the artist, his versions of Medusa and the sirens are intended to celebrate powerful females maligned by mythology, to reclaim their value, and for him, these works were important in defining his own identity as the son of a African-American LA-based hairdresser. It’s a solid room, where physical surfaces and materials have been sourced from real life, from hair salons and Home Depots, rather than the art supply store. The history of the materials imbues these abstract works various layers of meaning–mythological, historical, social, and political–elevating everyday materials and the struggles of those who use them.

The third gallery presents three of the giant paper pulp paintings Bradford has become most known for; “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” “105194,” and “Tomorrow Is Another Day” all contain vague hive shapes in undulating tones of red, ochre, and black, contained by buff tans and soothing blue-grays. Tomorrow also includes “Niagara,” a projected video from 2005, featuring a young African American man in basketball shorts, walking with subtle bravado on the Los Angeles sidewalk outside of Bradford’s studio, and it functions neatly as a physical and conceptual exit to the show.

“Niagara,” 2005 (video) and “105194,” 2016 with door to the temporary storage closet at left

“Niagara,” 2005 (video) and “105194,” 2016 with door to the temporary storage closet at left

In Venice, Bradford’s light-filled paintings felt cathartic and hopeful, as did the video, but this was emphasized by their contrast with “Oracle,” the darkest and most portentous work in the show. Installed inside the central dome, it gave visitors the feeling of being submerged in a dystopian American nightmare. “Oracle” was created last minute, just a week or so before Vernissage week, after Bradford had discovered that the New York Times had published photos of the dome project without his permission–or so he thought. In reaction, he pulled down the original version, which was wallpapered in ‘We Buy Houses’ signs, and created this new piece, seemingly overnight.

Most artists would unravel in this last-minute decision, but Bradford was pushed to his creative limits and came out on top. He is clearly an artist who succeeds when he thinks on his feet and the intense, reckless energy of “Oracle” formed the heart and soul of the show. Without it, we stroll through two galleries of large abstract paintings of varying color schemes whose street- and Home Depot-sourced materials subtly comment on the reality of growing up black and gay in urban America, but without a menacing and contrasting force to orient them. The presence of these last few paintings is reassuring, but they don’t take any risk in being here either, rendered oddly neutral.

“Oracle”, 2017 in Venice with “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” 2016 in the background

“Oracle”, 2017 in Venice with “Go Tell it on the Mountain,” 2016 in the background

While it wasn’t a mistake to bring Tomorrow from Venice to Baltimore, this exhibition missed an opportunity to rigorously embrace a site-specific approach central to its success. Knowing how quickly and effectively Bradford works when he needs to, a large installation created specifically for the BMA would have been exponentially better than building a giant wall and storing the museum’s contemporary holdings behind it. The extra gallery space could have been filled with projected videos selected for a Baltimore audience, or the artist could have created an even larger, trashed and threatening version of “Oracle,” based on all that we’ve experienced as a country (or city) in the past two years.

If you appreciate the power of site-specificity and the energy generated by context for this particular collection of works, a consideration of place and time should have been an essential part of realizing this sequel exhibit in Baltimore. The adjacent gallery, full of screen-printed T-shirts and tote bags, the result of a highly publicized collaboration between Bradford, the museum, and children from Baltimore’s Greenmount West Community Center, feels like an add-on, a hollow gesture. No amount of cute museum swag made in Baltimore, nor the giant yellow banners emblazoned with the children’s photos and “super hero” slogans can access the power of context unless the work in the show and its curation reflects a keen eye towards Baltimore.

Bradford’s Venice exhibition in Baltimore is proof that it is not enough to simply transport the exact same works, in the exact same order (minus a last minute installation inside a dome) to a new venue and expect the same results. Baltimore isn’t Venice and our national political climate has evolved significantly in the past two years. It is reasonable to expect a great artist, curatorial team, and institution to recognize a new context is a chance to generate rich site-specific content, rather than treating it as a neutral space to be automatically filled.

Audiences in the Baltimore region deserve the same deference as those in Venice; and for this exhibit to maintain the political, social, and emotional intensity created in tandem with its environment, it must acknowledge place, time, and history. As it is, Bradford’s Tomorrow (Part 2) requires more substance, questioning, and risk-taking from one of America’s most powerful artists and an institution staking a claim based on equal relevance for local and global engagement.

Bags and T-shirts, Collaboration between Mark Bradford, the BMA, and the Greenmount West Community Center

Bags and T-shirts, Collaboration between Mark Bradford, the BMA, and the Greenmount West Community Center

Mark Bradford: Tomorrow Is Another Day at The Baltimore Museum of Art is up through March 3, 2019.