Rachel Whiteread’s First Comprehensive Survey in America Questions the Authorship of Monuments and Authority of Masculinity by Dr. Jordan Amirkhani

For as long as I can remember, the open atriums on the lower and entrance levels of the National Gallery of Art’s East Building have served as a presentation space for large-scale sculptural and painted works by the grandest leaders of the 20th century modern tradition. Richard Serra’s Five Plates, Two Poles (1971), 15 tonnes of hot-rolled steel plates leaning precariously upon one another, stand like giants, aggressive and anxious amidst the swells of tourists jostling between the cafeteria and the galleries. Robert Motherwell’s Reconciliation Elegy (1978), commissioned for the opening of the building in 1978, swells wide on the wall, announcing itself from every vantage point within the open funnel of the building as exemplar of modernism’s deepest notes.

As a building made in conscious support of artistic statements of this size and scale, the NGA’s East Building has always functioned for me as a deeply gendered and politicized space where the “great” works of men appear in their natural habitat, structuring the store from the entrance forward, eliding the many absences, invisibilities, and struggles that mark the history of art and its institutions today.

Thus, I was shocked when I entered the building a few weeks ago to see the British artist Rachel Whiteread’s Untitled (Domestic) (2002) standing tall and proud in the lower atrium—the first work encountered in the NGA’s current retrospective of Whiteread’s work, which covers the span of almost thirty years of artistic output. More than a curatorial introduction to Whiteread’s formal and materials concerns, Untitled (Domestic) also functions as an ideological destabilizer, quietly disturbing the atrium’s commitment to a certain kind of male authorial voice.

Rachel Whiteread. Untitled (Domestic), 2002. Cast plaster on various armatures, 676 x 583.88 x 245.11 cm, weight: 8493 lb., Collection Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Owned jointly by Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; George B. and Jehny R. Matthews Fund and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Henry Hillman Fund, 2006 @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

Rachel Whiteread. Untitled (Domestic), 2002. Cast plaster on various armatures, 676 x 583.88 x 245.11 cm, weight: 8493 lb., Collection Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo, NY. Owned jointly by Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo; George B. and Jehny R. Matthews Fund and Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Henry Hillman Fund, 2006 @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

A plaster cast of the negative space of a staircase and its ballustrades as grand and imposing the works that have laid claim to that arena in the past, Whiteread’s icon to emptiness, interiority, absence, and the domestic proposed a different but no less powerful project for the history of sculpture—one where absence, ephemerality, and the space of the home move from the margins to center. In light of the absences and silences that mark art institutions large and small, the National Gallery’s current retrospective of British artist Rachel Whiteread stands as an important corrective to the male-dominated languages and traditions of sculpture that shape the history of modernism, and proposes the artist as not just an inheritor of those traditions, but as central to the genre’s history and continuation in the twenty-first century, a significant win for a genre where women continue to be underrepresented in historical narratives despite the great number of women working in the field.

A master materialist deeply in tune with the capacities and limits of a range sculptural processes, project sizes, and media (concrete, resin, and even pink dental plaster all submit under Whiteread’s hand), Whiteread’s engagement with seemingly impossible assignments (plastering the interior of an entire home, for instance) or fraught subject matter (such as creating monuments to commemorate the Holocaust and 9/11) establishes her as a bold artist working in complete thoughts—as if weakness, irresolution, or failure is not granted the space to name itself in her world.

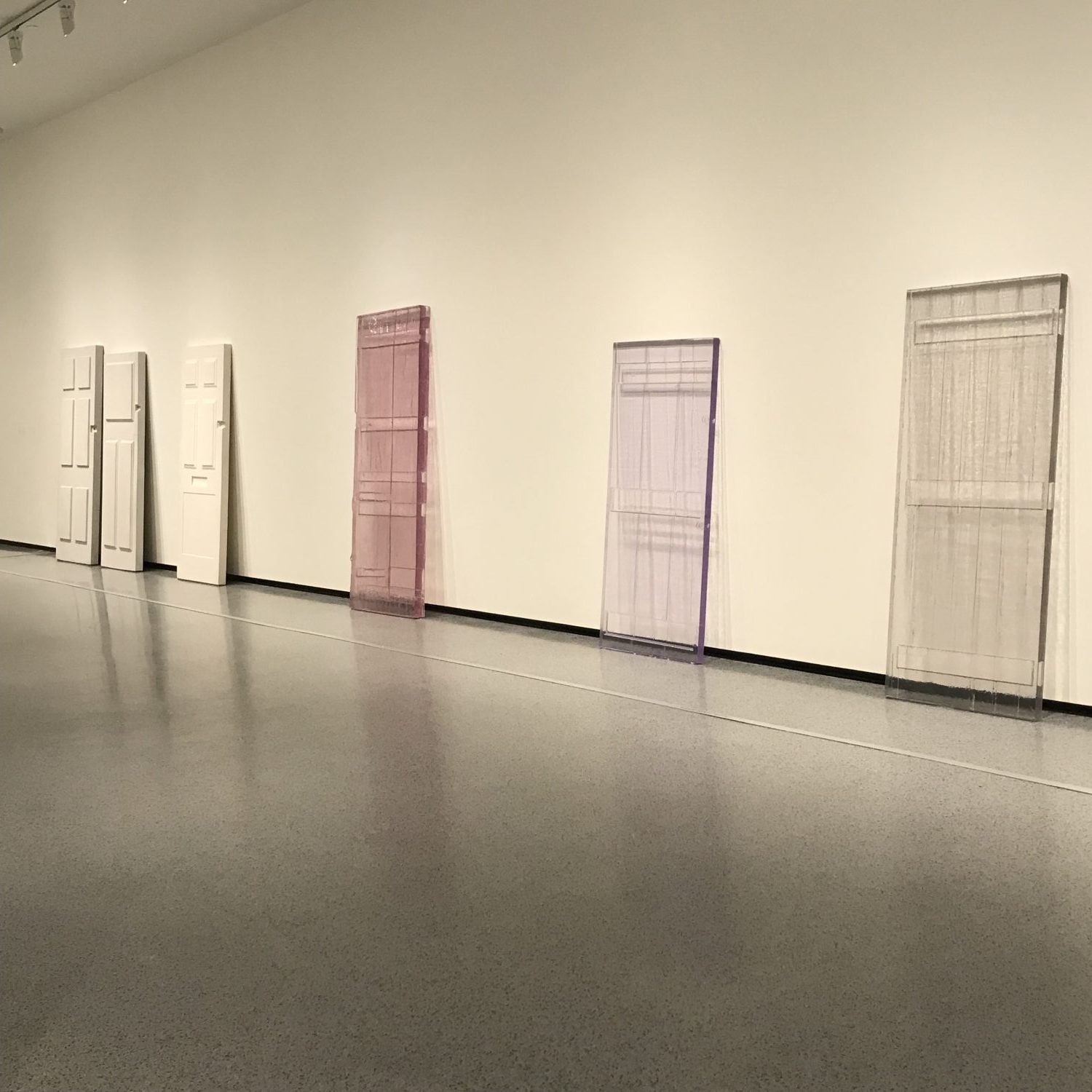

Rachel Whiteread. Untitled (Twenty-Five Spaces), 1995. resin, variable dimensions. Private collection © Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

Rachel Whiteread. Untitled (Twenty-Five Spaces), 1995. resin, variable dimensions. Private collection © Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

The exhibition considers a series of important moments and series within Whiteread’s career chronologically, beginning with the collection of works presented in her first solo exhibitions at the Carlisle Gallery in London in 1988 and the Chisendale Gallery in 1990 that made her famous in her home country, and ending with three collage-drawings from 2012 that point to the significance of drawing and collecting to her practice.

Exhibited together in 1988, Shallow Breath, the space underneath her father’s bed, Closet, the interior of a wardrobe covered in black felt suggesting the warm coziness of a children’s hiding place, Mantel, and the first Torso, a series of hot water bottles filled with various materials such as plaster and resin that capture the fleshy negative space of the interior of this banal but comforting domestic object, comprise a study of a young, struggling artist’s meager sleeping quarters and the common objects that fill a room, a life.

Rachel Whiteread, Shallow Breath, 1988. Plaster and polystyrene, 185 x 90 x 20 cm; weight: 672.403 lb. Courtesy of the artist @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

Rachel Whiteread, Shallow Breath, 1988. Plaster and polystyrene, 185 x 90 x 20 cm; weight: 672.403 lb. Courtesy of the artist @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Plaster on steel frame. 269 x 355.5 x 317.5 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Glenstone Foundation @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of the NGA.

Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Plaster on steel frame. 269 x 355.5 x 317.5 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Glenstone Foundation @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of the NGA.

Tender yet solidly constructed, these works point to Whiteread’s early ability to navigate where sculpture needed to go but had not yet gone. Turning away from the solid presences and forms of earlier British sculpture, Whiteread composes the negative spaces of sculpture’s surroundings and the indexical positions of the bodies that move and pull themselves around them. Whiteread’s breakthrough work, Ghost (1990) completes the sentence of these early work’s: plaster casts of an entire room’s walls in an old Victorian house in North London reassembled to articulate the void, or empty space used by the bodies that move in and out of it.

Whiteread has described the process and result of Ghost as “mummifying the air,” and so perhaps these objects extend themselves to another iteration of the artist’s embalming practice, preserving the setting of a life just as mummification preserved the corporeal matter of a life. Her profound ability to entangle the materialist history of sculpture to the corporeal and the bodily continue throughout the next galleries: bathtubs made of plaster and rubber operate as totems to the absent bodies who find solace in their watery, womb-like spaces; mattresses lean against walls, slouching like a body in rest, relaxation, or perhaps immanent collapse; casts of tables and chairs mirror the pairings and relations between two human beings, different in shape and scale, but nevertheless, bound together in their utilitarian dependence.

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Yellow Bath), 1996. Rubber and polystyrene. 80 x 207 x 155 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Henry L/ Hillman Fund, 1996 @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Yellow Bath), 1996. Rubber and polystyrene. 80 x 207 x 155 cm. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Henry L/ Hillman Fund, 1996 @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy of BmoreArt.

While the beauty and power of Whiteread’s work manifests across the entire scope of this exhibition, becoming subtler, softer, and more playful through time (I still cannot get the image of a large bubble marring the smooth surface of a Carl Andre-esque floor work out of my mind, nor can I forget the subtle color harmonies of a shelf of toilet paper rolls cast in colored resin), the artist’s series of public sculptures form the most dramatic and complex statements in the exhibition, particularly when placed in dialogue with recent removals of public monuments to colonialism and confederacy that have occurred here in the United States in recent years.

Whiteread has long questioned the role of the monument in an era of fraught social divisions and diluted collective values but continues nevertheless to propose that perhaps its role today is to ask questions of what we have memorialized in the past, who those monuments “speak” for, and what social role they should (or could) play.

Rachel Whiteread, Line Up, 2007-2008. Plaster, pigment, resin, wood, and metal. 17 x 90 x 25 cm. Private collection, New York @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy the artist and Mike Bruce.

Rachel Whiteread, Line Up, 2007-2008. Plaster, pigment, resin, wood, and metal. 17 x 90 x 25 cm. Private collection, New York @ Rachel Whiteread. Image courtesy the artist and Mike Bruce.

Navigating how to “display” large-scale site-specific monuments remains an obstacle for museums and the challenge is pressing for a retrospective of Whiteread whose most significant works will never appear in the gallery at all. However, the NGA’s inclusion of beautiful photographs, small-scale models, informative wall texts, and a longform BBC documentary of Whiteread’s life and work animates such works as the Nameless Library (also known as the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial) in Vienna (2000) and Untitled Monument displayed on the Fourth plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square (2001), offering the viewer a sense of the artist’s commitment to a genre struggling under the weight of its own history… our history.

In this way, we can understand Whiteread’s deep engagement with the past and present of her chosen medium to be a mere extension of a rich constellation of social and political commitments that structure her career as well—her commitment to drawing attention to the housing crises and socioeconomic ills that have mired British society since the Thatcher Era across a number of projects is the best example of this.

Forming an additional rejection of the modes of ahistorical formalism and “pure process” discourse that have shaped modernism and its meanings for decades, Whiteread’s work does not just pose a threat to the patriarchal narratives of sculpture and modern art that live on and breathe comfortably within the art institution, but acknowledges the institutional and ideological barriers to those who are cast aside by institutions of all kinds.

Author Bio: Dr. Jordan Amirkhani’s research and writing reflect her commitment to intersectional feminist critique and the contextualization of issues of gender, class, and race within the development of European and American art from the nineteenth century to the present. She is a regular contributor to Daily Serving, Artforum, and Burnaway, and serves as a Professorial Lecturer in Art History at American University in Washington, DC.

Rachel Whiteread at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC is up through January 13, 2019 in the East Building Concourse Galleries. The exhibition is curated by Molly Donovan, curator of art, 1975–present, National Gallery of Art, Washington, and Ann Gallagher, director of collections (British art), Tate Britain, London.

Photos by BmoreArt and courtesy of the National Gallery of Art.