A Discussion of For Freedoms, the Largest Creative Collaboration in American History, with Hank Willis Thomas at MICA by Cara Ober

Hank Willis Thomas is one of those rare artists who crosses over genres seamlessly–as a fine artist, designer, historian, advertising strategist, and political advocate. Or perhaps this isn’t such an unusual confluence after all? Thomas himself argues the opposite, that marketing and political campaigns are storytelling, and that artists are the best storytellers.

In his own career, he makes a strong case that every action one undertakes can be considered art and that one’s political convictions and aesthetics can, and should be, combined in order to do what artists do best: raise questions, expose complexity, make people uncomfortable, problematize social issues, and fight for justice.

Like Andy Warhol, the godfather to all those who appropriate popular images to make new ones, Thomas’s conceptual sculptures and photos rely on images lifted directly from historical archives and popular advertising campaigns. He has used brands such as Absolut and Nike to create searing political and social critique, exposing capitalistic domination and violence, but with humor and style. Like his mother, Deborah Willis, the professor, author, and photographer largely responsible for the contemporary cultural archive of black photographers dating back to the Civil War, whose scholarly research has changed the art historical and political landscape, Thomas envisions a more diverse and equitable world, where artists play a vital role in our nation’s consciousness and policies.

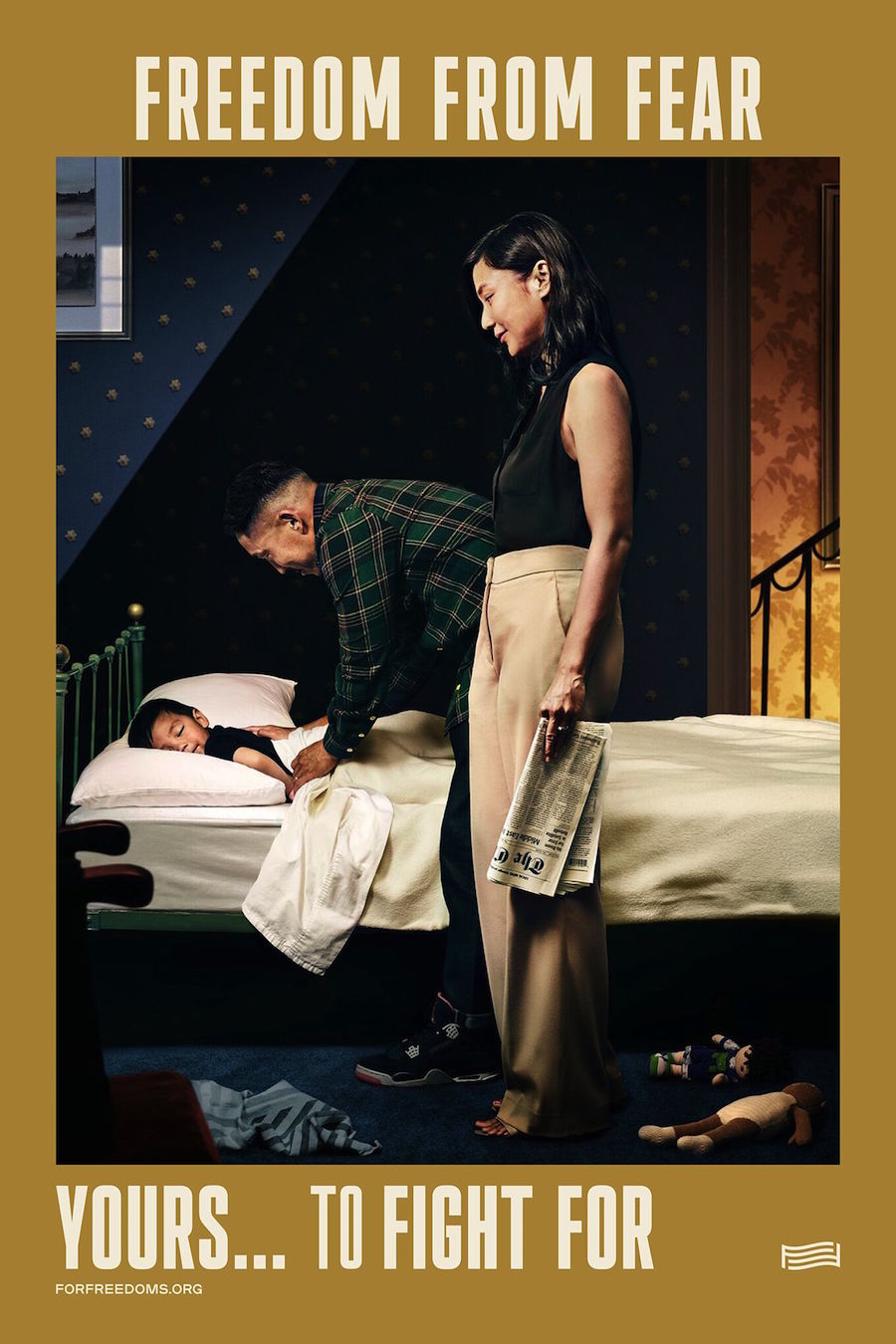

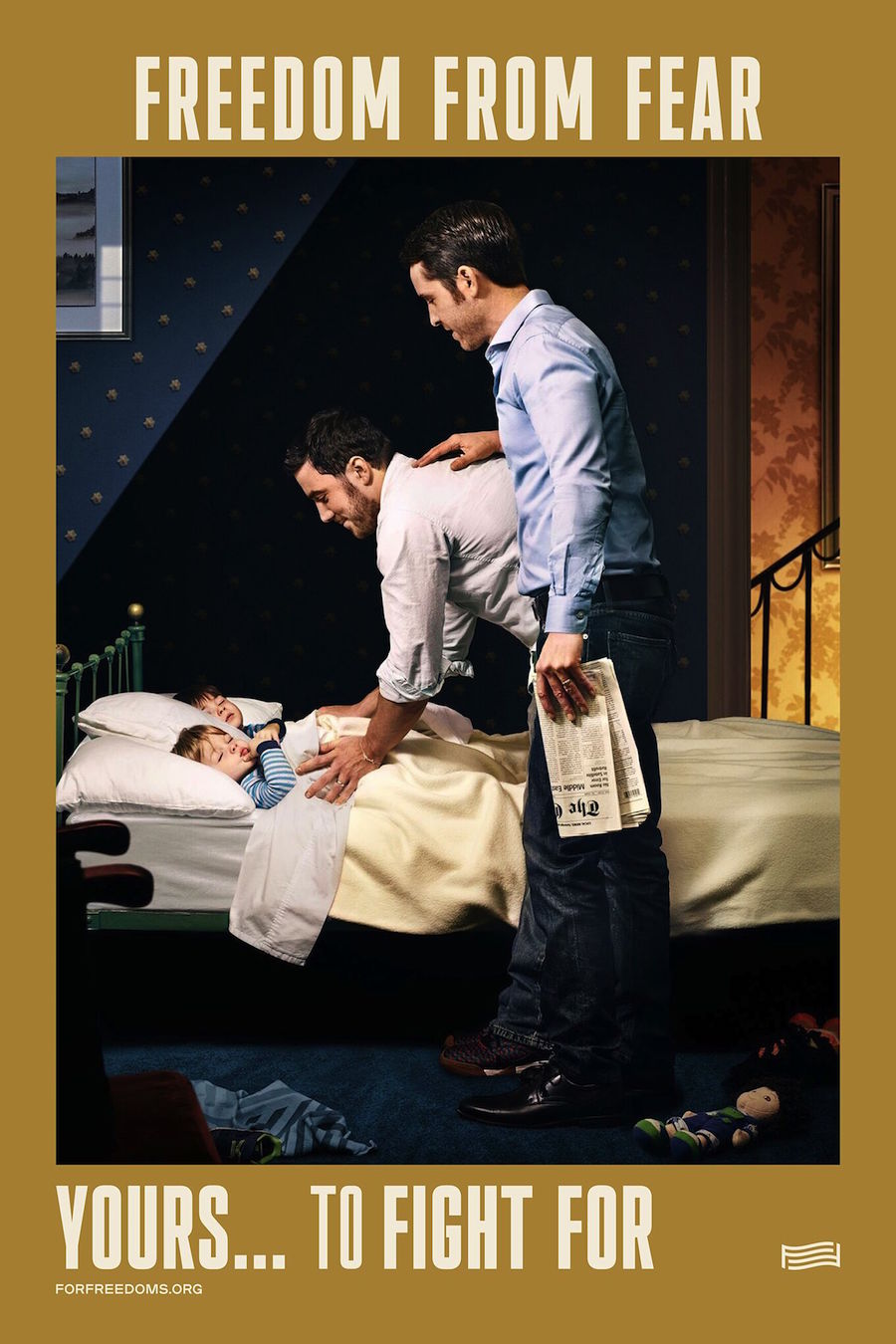

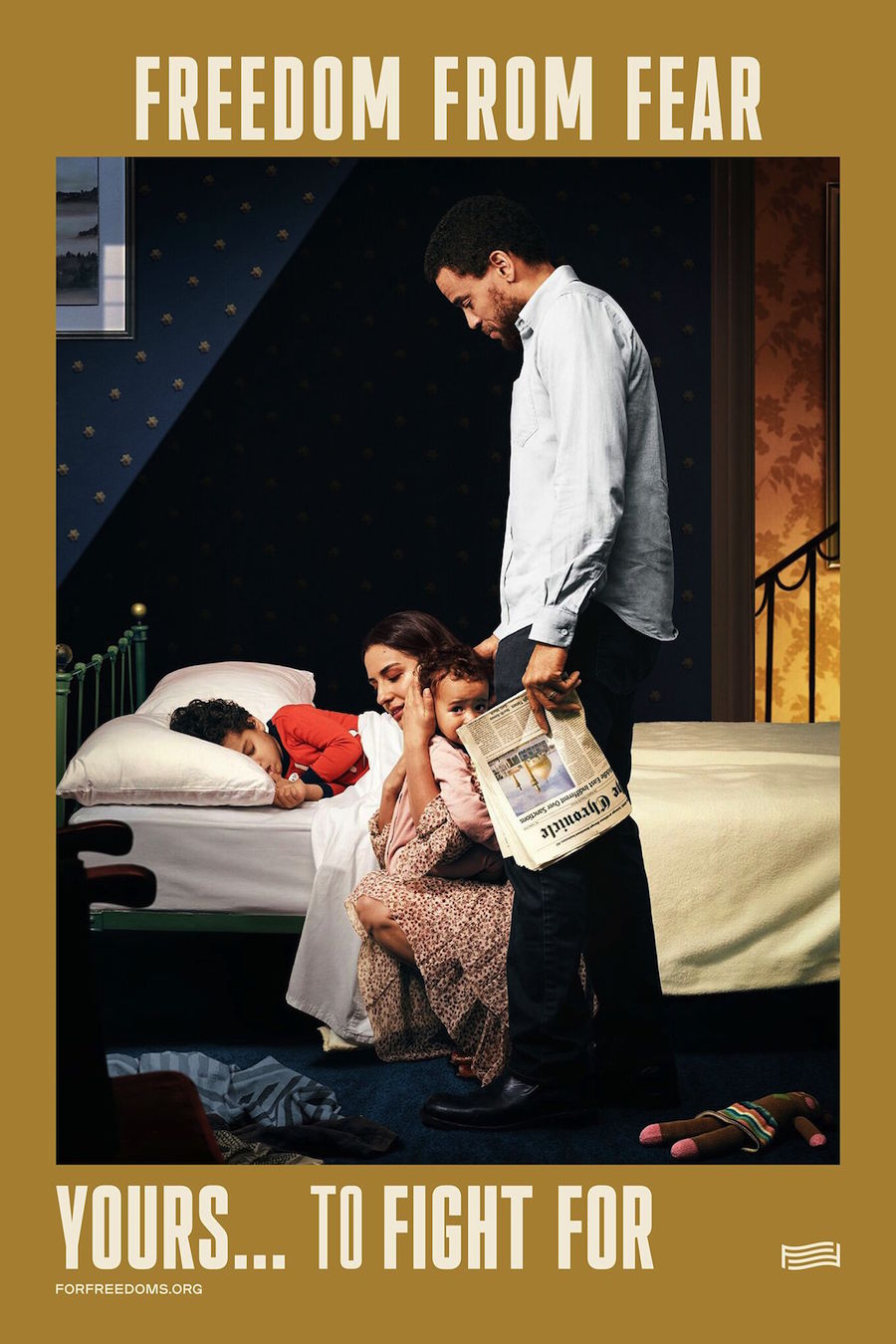

Interpretation of Norman Rockwell’s Freedom from Want by For Freedoms.

Interpretation of Norman Rockwell’s Freedom from Want by For Freedoms.

Photography by Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur

It was this desire that led Thomas, with friend and collaborator Eric Gottesman, to found For Freedoms as a Super Pac during the 2016 election season. The project grew into a 50 state initiative in 2018, with billboards displaying art by over 100 contemporary artists in all 50 states, town hall meetings across the country, and For Freedoms themed exhibitions in galleries and museums, as well as colleges and universities.

“Eric and I have been friends a long time and we talked about doing something every election season,” says the 42-year old artist in an interview, during his two day visit to the Maryland Institute College of Art in October 2018. “At some point, we realized our discussions would be much more interesting if we became a part of the actual process. The idea behind For Freedoms was that we could creatively engage with the political establishment through joining it.”

Since 2016, For Freedoms has evolved into a vast network of collaborative entities and projects, starting with billboards and town halls. “Our first project was an exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery in NY,” says Thomas. “We used it as our headquarters as we developed language, which would eventually lead to the billboards. We did a few town halls at ICP NY and in Neuehouse in LA, and then wound up doing a residency at MOMA PS1 the following year.”

ForFreedoms Billboard in Topeka, KS, photo by Jeff Scrogggins

ForFreedoms Billboard in Topeka, KS, photo by Jeff Scrogggins

Thomas said he realized firsthand that modern art had become legitimate and highly desirable because MOMA used it to proselytize their ideas and values across the country. Not only did MOMA host groundbreaking exhibitions in New York, they would travel them out to museums across the country, “to places like Kansas City and Iowa and St. Louis to show people that this is what modern art is.” Thomas says this is why so many strong modern collections exist across the country in even the most conservative regions. He realized it was a strategic campaign on behalf of the museum and saw it as a model for his own combination of art and activism in collaboration with institutions across the country.

“We realized that there are museums, colleges, universities, and billboards in all 50 states and wondered if we could do exhibitions, town halls, and billboards in all 50 states during the 2018 midterm election season,” he says.

“We are simultaneously working with institutions and artists and corporations across the country to make what we believe is the largest creative collaboration in American history.”

When I ask him how he made a switch from an individual artist to working with a collaborative political entity, he stops me. “For Freedoms is a conceptual work of art,” he explains. “Everything that we do is a conceptual art project. Every decision I make is part of my art practice, whether collaborative or solo.” He says that, even in his studio, he prefers working with a team, that every moment of our lives is a compromise.

Hank Willis Thomas and Cara Ober, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

Hank Willis Thomas and Cara Ober, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

“Compromise is what democracy is founded on. You don’t get your way all the time, but whoever makes the better argument or tells a better story gets the advantage.” Thomas acknowledged that many of his ‘fine art’ decisions came out of collaborations, citing “Absolut Power,” his series based on Absolut vodka advertising, and said his roommate, a graphic designer, helped him to make many of his aesthetic decisions. He says that For Freedoms continues to be an energizing and challenging project precisely because it’s not centered around him, or any one person, but about engaging with the entire country.

“We came to MICA early on because I knew Colette Veasey-Cullors and Sammy Hoi, and then I met David Bogen, and realized that a lot of institutions are doing civic work,” he says. “I think the reason that artists are so easily defunded and discarded is people don’t often recognize it as civic work. By partnering with institutions like MICA, and framing this project under the For Freedoms mantle, we lay the groundwork for a more powerful movement around civic issues, encouraging greater civic engagement in creative institutions.”

Part of Thomas’s visit to MICA included an advisory session with Curatorial Practice MFA candidates, who will be curating an official For Freedoms exhibition at MICA in January. Thomas believes that local institutions can offer a greater insight into the needs of global communities, and his desire to see these ideas within a larger national movement like For Freedoms is critical.

Hank Willis Thomas with MICA MFA Curatorial Practice Students, Photo by Justin Tsucalas

Hank Willis Thomas with MICA MFA Curatorial Practice Students, Photo by Justin Tsucalas

When I asked about his process for student engagement, Thomas explained that he had no preconceived expectations. “I approach everything like I’ve never done it before,” he says. “I just want it to be conversational and collaborative. I think my job is to ask questions; I try not to go into any space predetermined about how I will behave, and who is there, and how they will behave.”

Thomas confided that Baltimore is special to him because MICA was the first place he was offered a teaching job in 2005, thanks to then-graduate dean Leslie King-Hammond, a mentor to him. “I did my first residency at Johns Hopkins, thanks to Rita Walters, and had my first museum show at the BMA with I Am A Man in 2009. If it weren’t for Baltimore… I don’t know what I’d be doing.” Thomas was awarded an honorary doctorate from MICA last year, and then we joked about calling him Dr. Thomas.

Hank Willis Thomas speaking to a packed house at MICA on October 17, 2018

Hank Willis Thomas speaking to a packed house at MICA on October 17, 2018

Currently immersed with For Freedoms lectures, town halls, person-to-person meetings, and constant travel, Thomas said that it’s essential that artists realize that their political engagement (or lack thereof) is part of their practice; that they’re always making art-related decisions and their goal should always be to engage others in discourse, rather than to sell or simplify an idea. “We realized that artists are great storytellers and that we needed to have a seat at the table,” he says.

“As soon as you call something art, it allows people to think creatively about things they already know, but when you call it politics, people feel that something is at stake. So, as artists engaging in this way, we raise the stakes and make them more complicated.” – Hank Willis Thomas

We talk about the medium of the billboard, it’s history and limitations, and why For Freedoms selected it as a primary tool in its campaign. “Public space is contentious,” he explains. “Mostly, the signage in public space is used for way-finding and selling. And so, in a way corporations have a monopoly on speech in public space. And I think it’s fine for corporations to be in public space, but it’s important to have different voices as well.” Willis said that he thinks every single citizen should choose to participate in democracy, regardless of whether he agrees with their political views, that “the more people are engaging, the better for all of us.”

It is this commitment to open and sometimes contrarian discourse that separates Thomas and his team of artists and art administrators from politicians, pundits, and marketing professionals. Although some of the For Freedoms billboards have been markedly controversial and partisan, provoking complaints and protest in certain parts of the country, he says there were many artists who participated in For Freedoms who expressed political views that he did not agree with.

“I think we need to be more aware of what we’re buying into when we encourage certain kinds of speech in public and discourage others,” he explains. “Our hope is to not be divisive and partisan, but we also acknowledge that not everyone is going to fully understand and agree with what we do. We don’t agree with everyone who is part of the collective, but we recognize that the spirit of creative discourse and collaboration relies on trust. The idea of ‘Us and Them’ is comforting, but creates a false dichotomy. We don’t often point out to ourselves, or acknowledge that, from their perspective we are the them.”

“We need to see multiple sides of every experience because the truth is contentious, elusive, and dangerous.”

“We need to see multiple sides of every experience because the truth is contentious, elusive, and dangerous.”

Thomas, based in NY, mentions that he had flown in from Boston that morning and would be taking trips to Los Angeles later in the week, dotting back and forth across the country with an itinerary that gives me a sinus infection, just thinking about it. I ask Thomas if he is an extrovert, if the energy from collaboration and travel helps to energize him for the brutal schedule.

“There are about 20-30 people on our core team, and a lot of us are traveling and going from here to Nebraska to the South Side of Chicago to Delaware to Texas, and it’s just amazing to see all the different things people are doing,” he says. “But no, I’m not an extrovert at all. I am just excited about this work, about getting the work of 100 artists on the billboards. Seeing the response to all of it is hyper-fulfilling, especially the work of the art administrators who are doing incredible work and getting the billboard art up.”

Thomas said that found working alone boring, that he receives more energy from this project than he puts in, a sign that it’s working. I asked about his history as an artist-provocateur, where many of his projects have incited protest, confusion, media controversy, and anger and he is circumspect. “If nobody gets mad, you’re doing it wrong,” he smiles. “I want everyone to get along, but it doesn’t seem like the way of the world and this is the whole point of political discourse.”

We talk about the loss of his cousin’s life in a robbery in 2000, where he was shot dead and the resulting work, ”B®anded,” Priceless #1, 2004 (With thanks to Albert Ignacio), made to honor his memory and protest America’s epidemic of gun violence. The work, which resembles a Master Card advertisement, garnered protest and confused public responses when it was hung on the outside of the Birmingham Museum of Art.

Hank Willis Thomas, “B®anded,” Priceless #1, 2004 (With thanks to Albert Ignacio)

Hank Willis Thomas, “B®anded,” Priceless #1, 2004 (With thanks to Albert Ignacio)

“Why should I have to hide my pain to make people like my art or feel comfortable? I just find it hard to separate my art from anything else I do,” he says. “Which is I think maybe what keeps it authentic. I don’t know how to do anything without a creative approach. I’m not formal, and I’m not consistent, but I think it’s working.”

I ask about the panel discussion to occur later that day at MICA with institutional and cultural leaders on stage, about whether it’s an authentic vehicle for real change or a political performance in an age where social justice is cultural currency. In true HWT fashion, he answers me with a challenge. “Well, what’s wrong with that?” he asks. “Our leaders aren’t perfect and neither are their motives.”

He continues, “Maybe part of the problem is we are waiting for a hero, and not choosing to be our own. We want someone else to be perfect and authentic and have all the right values, in order to be someone we can get behind… This is because we are afraid of people seeing how flawed we are, that’s why we don’t put ourselves out there.”

Thomas shakes his head. “One of the things you can say about our president, he doesn’t acknowledge a single flaw, but he’s shown us that you can use multiple flaws to your advantage.”

We talk about 45, and I ask if he thinks that Trump’s presidency is an ongoing absurdist performance piece. “For Freedoms was conceived before Trump was even running for president, but there’s a lot to learn from him,” says Thomas. “The story is not fully written, but there is much to learn about how you can use storytelling techniques to convince people to buy into things they’d be otherwise strongly opposed to, or that they were opposed to until it was brought to them in a compelling way.”

Hank Willis Thomas, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

Hank Willis Thomas, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

We discuss the value of entertainment and spectacle, and the media landscape that purposefully and also unintentionally anointed a president so utterly different than Barack Obama. “Things weren’t perfect under Obama either,” Thomas acknowledges. “Yesterday’s Democrats are today’s Republicans and vice versa, and what does that say about tomorrow? The idea of any Messiah, be it Trump or Obama, is problematic because it means that the rest of us should just rest on our laurels and let them do what they’re going to do.”

He continues, “If there’s anything we can learn from these two very unlikely presidents, it’s that you can make history and write your own story, and that it doesn’t work any more to play by the rules. This is why I feel that artists are uniquely suited to get into the game–because we don’t play by the rules and we never have. Whether it’s fine artists or graphic artists or filmmakers or musicians, we have mastered the art of seduction. We have learned how to use our talents to the greater benefit of us all.”

I ask if he is suggesting that more artists run for office, or that we are our own worst problem sometimes, in terms of not being ambitious or collaborative enough. “I’m optimistic and tend to think of it in a larger arc,” he says. “I don’t know why we are on this planet, but I think we are headed in the right direction, even with the impending doom of the environment and the great political fears that many of us have, which may be warranted. We don’t have the benefit of looking backwards from the future, but from where we are–looking back, things are way better than they were before.”

For Freedoms Projects including: Billboard by Sadie Barnette in Nashville, TN, For Freedoms Phonebanking, Town Hall at Aspen Ideas Festival, Jenny Holzer bus for For Freedoms in LA, the Resistance Revival Chorus, and Lawn Sign installation at U of South Florida

He shrugs and says, “Just the fact that we are sitting in a confortable room right now, and we are not afraid, at least in the US, to use our voices is significant. We would like to have more liberty and safety, but the tenuous safety we have is much more than previous generations had, and the fact that we care more about one another, especially across the world, than we ever did before, and are more closely connected is good. I’m not saying it’s going to be easy, but this is not going to stop. We have to be willing to change our minds and evolve.”

“I think it’s important to be visionary, not reactionary, and to not to be binary in our thinking,” he says. “I want artists to always look for not the 3d way but the 10th or the 100th way and not be so easy to conclude. When I think of the effectiveness of this project – if it inspires even just 10 artists to realized they can do more, that there’s so much more to do, we are successful.”

It’s still fairly early in the day and Thomas rubs red and bleary eyes. A MICA team waits for him out in the hallway and is ready to whisk him away to lunch, to meetings with students, and to two public ‘town hall’ style lectures in Falvey later that day. I ask about his ability to maintain energy for all of this, but he expresses nothing but confidence about the future.

Interpretation of Norman Rockwell’s Freedom from Fear by For Freedoms, Photography by Hank Willis Thomas and Emily Shur

“In 2020, if we do another 50 state initiative ahead of midterm elections, which would include registering people to vote and encouraging people to get involved in civic discourse, I hope we do it bigger, better, and smarter,” he says. “I hope that it’s no longer about one or two or 50 5000 of us, but about all 300 million of us in this country. I want to see more of us engaged and taking ownership. I want to see us recognizing when we overstep, and to make amends and make space. I think we’ll all be better off. The world’s problems won’t ever be solved, and this shouldn’t be our goal. I think that increasing and improving the quality of the discourse is realistic.”

We pause and say goodbye, acknowledging the packed day ahead of Thomas and I am thankful for the energetic exchange. He puts on a black leather motorcycle jacket and starts to walk out, but then stops.

“The best thing about being an artist is that we are actually making our dreams come true every day,” he says. “And every moment and everything we do should be seen as part of our creative practice, especially the way we interact with other people–the capacity and responsibility to try and sometimes fail–to make every moment special. And to me that’s the fundamental reason for doing what we do.”

Hank Willis Thomas and Cara Ober, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

Hank Willis Thomas and Cara Ober, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA

More information: For Freedoms website

Top Image: Hank Willis Thomas, photographed by Jill Fannon at MICA