My Art, Laurie Simmons’ Feature-Length Film, Questions The Notion of Self and Reinvention by Cara Ober

It doesn’t get any more meta than playing the mother to your actual daughter’s character in a film shot in your own apartment and studio. Especially when the film is Tiny Furniture (2009), Lena Dunham’s coming of age flick chronicling the trials and tribulations of a recent college graduate who moves back home with her mother, a successful NY artist.

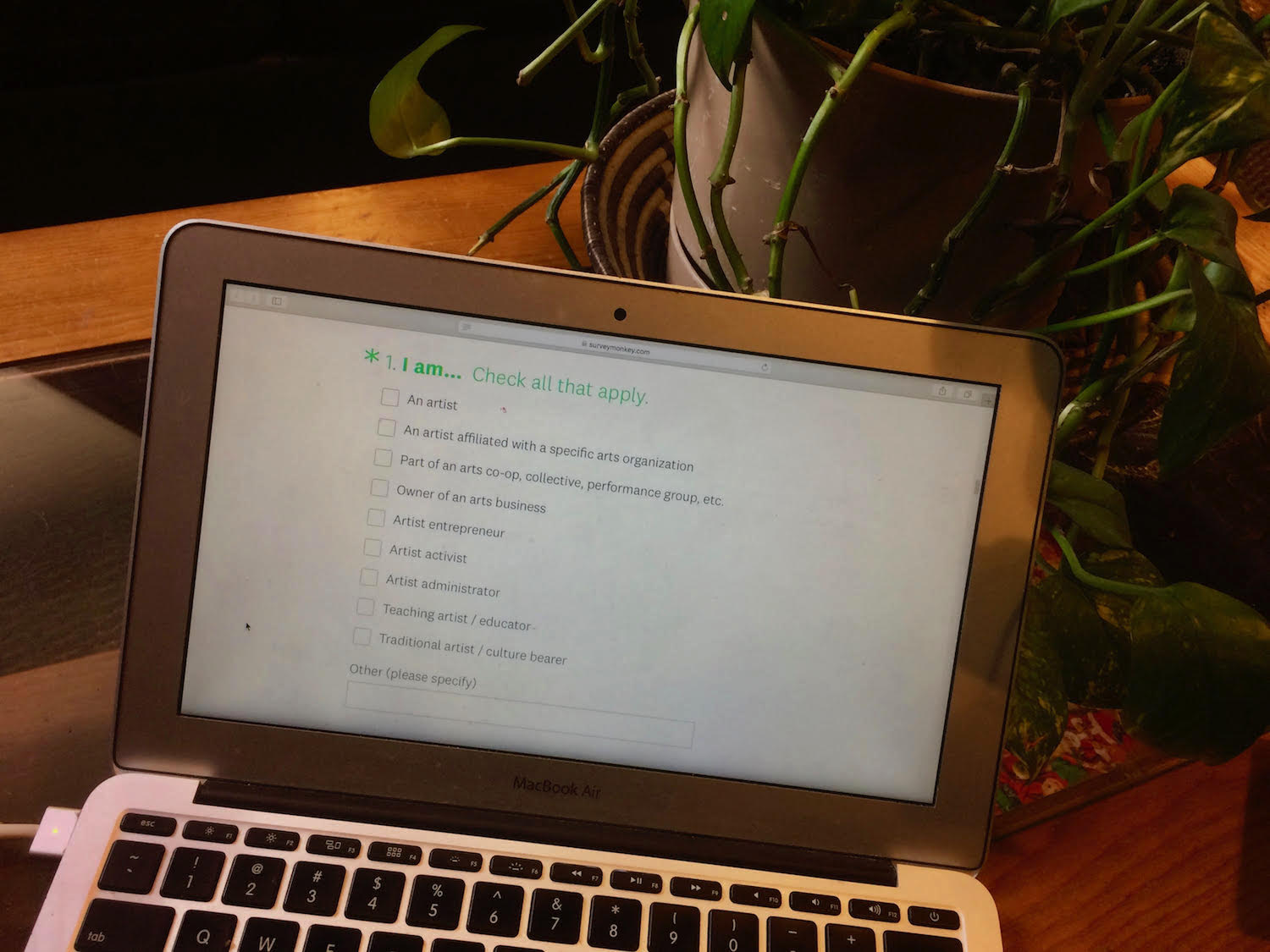

As Siri, Dunham’s mother in the film, artist Laurie Simmons not only invented a different persona and staged her apartment, but she created ‘fictional art’ to fill her character’s studio. When I asked her why she didn’t want to include her own artwork, widely known photo portraits that incorporate props, paint, dolls, and masks, she said she was playing a fictional character and the purpose of the artwork was character development.

Laurie Simmons and Lena Dunham in character in Tiny Furniture

Laurie Simmons and Lena Dunham in character in Tiny Furniture

“Tiny Furniture was shot where we live,” she recalls. “My life was shut down for 20 days and I was there for all of it. It was low budget and no one was doing set design, so every time we shot in a different space or a room, I could really prop it and set up the way I wanted. I designed my own costumes and could wear whatever I wanted. Everything happened so quickly–I had so much more freedom than one normally would on a film set, because people were not paying attention.”

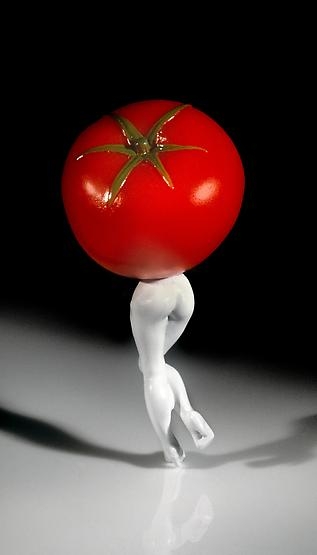

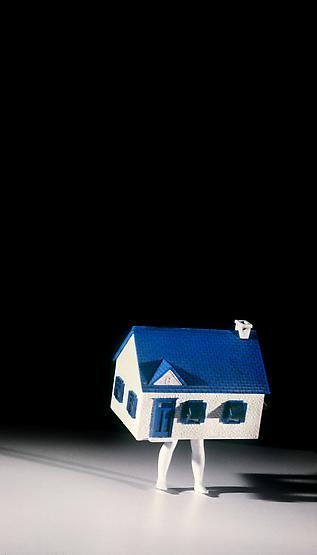

This rapt fascination with mise-en-scéne should come as no surprise. Props, costumes, and staged settings have animated Simmons’ photos since the mid-1970s, building a pointed commentary on the artifice of domestic femininity with an aesthetic rooted evenly in fashion photography and Dada. Baltimore audiences will recall a mid-career survey, The Music of Regret, at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1997, and her large black and white photo depicting a house atop a woman’s legs from her “Walking Objects” series is currently on display in the three year Imagining Home exhibit there.

Laurie Simmons “Walking Objects” series

Despite a robust career making still images, Simmons is not new to filmmaking. She made her first in 2006, The Music of Regret, a 45-minute musical in three acts starring Meryl Streep and the Alvin Ailey dancers. It premiered at the MoMA, and, according to the artist, was “too long for a museum and too short for the film circuit.”

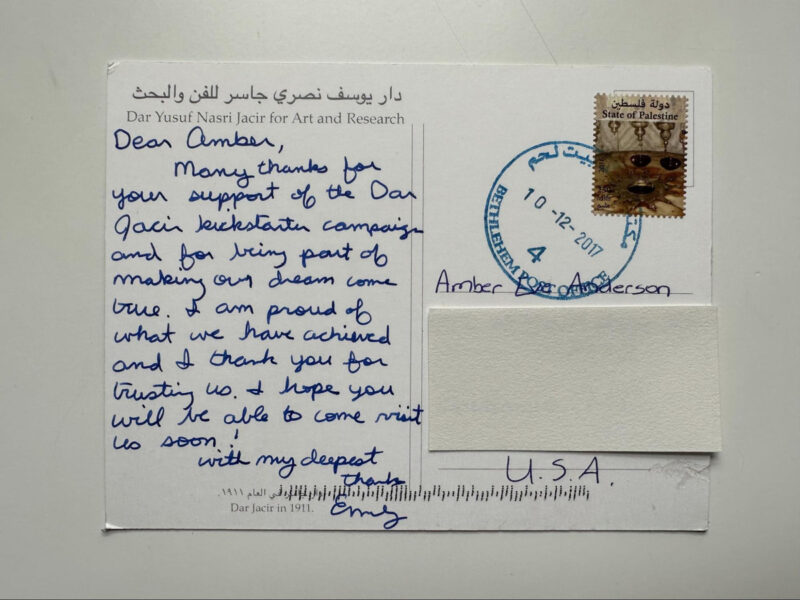

Twelve years later, she has produced a feature-length film about a middle-aged artist’s search for meaning and selfhood. Earnestly titled My Art, Simmons has created several parallel art practices for herself in the process–as a filmmaker, director, and an actor playing an artist who makes films and images. [My Art screens this Friday September 14 at 7 pm at The SNF Parkway, in an event where Simmons will be present for a Q&A afterwards with actor John Rothman.] In her new film, the artist plays Ellie, a single, middle-aged NY artist and art professor who struggles to find her mojo as an artist. Ellie travels to upstate New York to house sit for a friend with her handicapped dog over summer break in order to regain creative focus and inspiration.

Billed as a “coming of middle age” film for creative people, I find myself intrigued by the movie itself and the questions it raises, but equally by the idea of an artist making fake work as a fictional character loosely based upon herself for a film. Who are artists, really? Are we ever our ‘real’ selves in the work that we make? Or, is our creative work always an attempt to discover who we are, especially the hidden parts of ourselves? Can an artist’s daily life and artwork ever really be separated? And if so, do we have the freedom to be different artists all at the same time?

“I had to make photographs and art for both Tiny Furniture and My Art, which is its own kind of challenge,” Simmons confides. “It got really dicey recently when I had a conversation with someone who may prefer Ellie’s work to mine. I have had people ask me, have you ever considered making work like Ellie’s? And I say that I did make it, but I didn’t make it as me.”

In a way, Simmons’ departure from decades of photographic image making into film is a foray into a parallel practice. “Making a movie was so different for me than my art practice, so pure in a sense because people don’t know me as a filmmaker,” she says. “I am not a part of the film world, and I made this film purely for me. When I started it, I had no idea how many people would see it or if it would even have a public screening beyond the art world. There were no guarantees, so that made me into a young filmmaker, to feel something fresh and new and terrifying.”

Laurie Simmons as Ellie in My Art

Laurie Simmons as Ellie in My Art

Simmons said that, despite being a female artist based in NY of a certain age, Ellie’s character isn’t really based on her, rather she is a compilation of a number of women artists she knows well, so she feels familiar. “One thing that the film does is present artists as workers and thinkers, to portray the artist’s journey honestly and without cliché,” she says. “The other is to present a woman as a dynamic and powerful artist, especially at an age where women tend to disappear from the the art world.”

Simmons envisions My Art screening in movie houses with popcorn rather than a black box theater in a museum. Her desire to portray artists authentically to other artists–and also to also make them appealing to a general population–is admirable. In addition, presenting herself as the main character, a single middle-aged woman in the process of discovering her own creative power, as well as the love interest of several of the male characters, presents a direct challenge to the art and film world’s emphasis on youth, especially young women. In developing the character of Ellie, Simmons speaks to a universal need in all human beings to discover meaning and self awareness through new places, people, and adventures. Ellie starts the film at an age often deemed too undignified to start over as an artist and to take creative risks; in doing this she opens the door for the rest of us to consider new beginnings.

“All artists need to reinvent ourselves, absolutely and continuously,” Simmons says. “The challenge is to constantly raise the bar and never become complacent or bored. In a sense that’s where the title of the film comes from. Another way to think about making art is to dream up the art for another purpose, one that isn’t mine. There is a double meaning for me in the title, because it raises the question–is this my art? Is this movie my art?”

Lena Dunham and Laurie Simmons in My Art

Lena Dunham and Laurie Simmons in My Art

I agree with Simmons and wonder, if artists removed the limits we place upon ourselves to make a certain kind of art, if we freed ourselves from the reputation we have carefully built, what would we make? Every artist gets bored and tired; we all get depleted by our creative process. If we gave ourselves permission to make work that we don’t take completely seriously, essentially the way Simmons has in making a narrative feature film, what would that look like? As artists, we can’t help but let our imagination wander to the work we wish we had made, the work that seems too silly, sentimental, or inappropriate. But is this healthy and productive? And if we let ourselves make work as a different or parallel artist, is it still ours? Of course it is, but intention forms the boundary.

Simmons and I talk about Jack Whitten’s show at the BMA, now up at the Met Breuer. Simmons’ friend Roberta Smith just reviewed it for the New York Times and her essay is centered around the idea of Whitten’s secret artist self creating parallel but separate bodies of work that informed one another. Although Whitten had not originally intended his sculptures to be exhibited, and made it for private and experimental purposes, he eventually realized that these two disparate practices were inextricably linked. To me, this was the point of exhibiting Whitten’s sculptures and paintings together, and why I was excited to see images of his sculpture installed next to his paintings in the NY Times review, unlike the BMA where the sculpture and paintings were displayed separately.

Simmons’ film, parallel to her long history as a visual artist and photographer, tackles similar questions. Can an artist take on an alternate identity, or a secret one, and produce parallel works that are so radically different that they can be separated from one’s self? In Whitten’s case, the separation came from logistics and purpose, and also from a desire to control his public reputation and build a market. For Simmons, it’s about the intent for creating the art, with the art made in the movie functioning as a prop for character development. I can’t help but wonder, though, if one day Simmons will reconsider the line between the ‘fictional’ art she has made for films and her professional fine art practice–if there is a purity and energy to this faux art that is just one step beyond a photographer who decides to make a film?

Simmons as Ellie with her handicapped dog in My Art

Simmons as Ellie with her handicapped dog in My Art

“The art in the movie is Ellie’s art,” she insists. “Ellie for me is a fully formed character. After writing about her for so long and making the movie, I can tell you what what she likes to eat and read, or about her ex-boyfriends… She is not me.”

For me, this friction between actual-self and fictional character is where things get really interesting. While I recognize the need to produce a definitive body of work that provokes some kind of response from the art world, I also believe that a lack of clarity and a willingness to wander in mysterious, possibly unsuccessful places, can produce the most substantial art. This is what has me most excited about seeing the film, viewing it as a radical extension of an established body of work and also as an model for refashioning oneself artistically through a narrative medium and process.

When done well, medium and message are synonymous. For Simmons, the making of a narrative, feature-length film with characters that are compelling beyond the art world was her motivation for moving in this direction. “The challenge of making a movie visually and conceptually–being a director–was as close as I have come in making art that fulfills a dream,” she says. “There is a purity in making this film. It’s me scratching the itch of an obsession in the midst of a fever dream. I just had to get it made.”

My Art screens Friday, September 14 at 7 pm at The Parkway, followed by Q&A with Laurie Simmons and John Rothman

MY ART

Director: Laurie Simmons

2017, USA, 86 minutes, Digital, Not rated

Language: English

Cast: Blair Brown, Robert Clohessy

Distributor: Film Movement

Laurie Simmons is an American photographer, artist, and filmmaker and the mother of award-wining actress Lena Dunham of Girls fame.

John Rothman, a Baltimore native, is an accomplished actor and writer best known for his roles in Gettysburg (1993) and Ghostbusters (1984), also appearing in The Devil Wears Prada and The Day the Earth Stood Still.