The 13th Annual Sondheim Exhibition of Finalists at the Baltimore Museum of Art by Maura Callahan, Rebekah Kirkman, and Cara Ober

Is it possible that Baltimore’s annual Artscape prize is shrinking? And that this might actually be a good thing? The 13th annual Janet & Walter Sondheim Prize is still $25,000, but the exhibition of finalists, housed in the Baltimore Museum of Art’s basement galleries, is compressed this year into a smaller and better curated show featuring a diversity of artists, although the range of content on display is consistent with past years. The 2018 exhibition features works by Erick Antonio Benitez, Nakeya Brown, Sutton Demlong, Nate Larson, Eunice Park, and Stephen Towns, and one of the six will receive the fellowship based on the works on display at the museum.

In previous years, the exhibition of finalists has been hosted by The Walters or the BMA in galleries roughly double the size of this one, some with expansive ceilings and soaring walls. The opportunity to work at a monumental scale has been significantly valuable to past finalists, including Stephanie Barber’s interactive studio setup, Maren Hassinger’s two-story pyramid of pink inflatable bags, FORCE’s quilted wall installation, and Zoe Charlton’s site-specific wall collages, pushing artists to new experimental heights but also forcing them to take more risks, which is not historically a role museums seem comfortable with.

This year, it’s worth noting that a BMA curator’s name is on the wall text in conjunction with BOPA, while in past years BOPA’s Kim Domanski served admirably as a guest curator without any explicit institutional ownership. Assistant Contemporary Curator Cecilia Wichman’s influence on this year’s Sondheim finalists exhibit has helped build a series of six cohesive mini-exhibits that function independently of one another, but also forge a sense of camaraderie in the gallery, where a shared space allows for subtle formal connections and questions about Baltimore’s influence upon their ideas.

As with past years, it’s anyone’s guess who will win the prize. Jurors Lauren Cornell, Margot Norton, and Kameelah Janan Rasheed will meet with each finalist in the gallery and interview him or her before selecting the winner and awarding the prize on stage, American Idol-style, on Saturday, July 14 in the BMA’s auditorium.

While we applaud the continued support for artists that the Sondheim prize provides each year, we are also curious about its effect on the region. Now that it has existed for 13 years, is there a measurable impact? Are the artists of the region as engaged with the competition as they were when it first began? It is unclear whether this prize is more significant because it awards $25,000 to an individual or collective each year or because it provides the opportunity for regional finalists to exhibit in a museum setting, which was an even more scarce occurrence a decade ago.

What can the area’s hosting institutions like BOPA, the BMA, The Walters, and MICA do to continue to compress the Sondheim into its most viable format, but also to maximize the potential of this award and inject more energy into the process? We also wonder if there is a way to better connect the collective energy that forms around the exhibition of Sondheim semifinalists, hosted each year at MICA during Artscape, to the exhibit of finalists, which is more formal and remote in location.

Despite a relatively diminutive size, the 2018 exhibition of Sondheim finalists at the Baltimore Museum of Art offers a chance to engage with some of the best artists based in the region. Looking ahead, we would like to see a continued and more strategic effort to edit, curate, streamline, and promote this prize and accompanying exhibition because the artists of the region deserve it. (Cara Ober)

The following mini-reviews of each 2018 Sondheim Finalist were written by Rebekah Kirkman, Maura Callahan and Cara Ober.

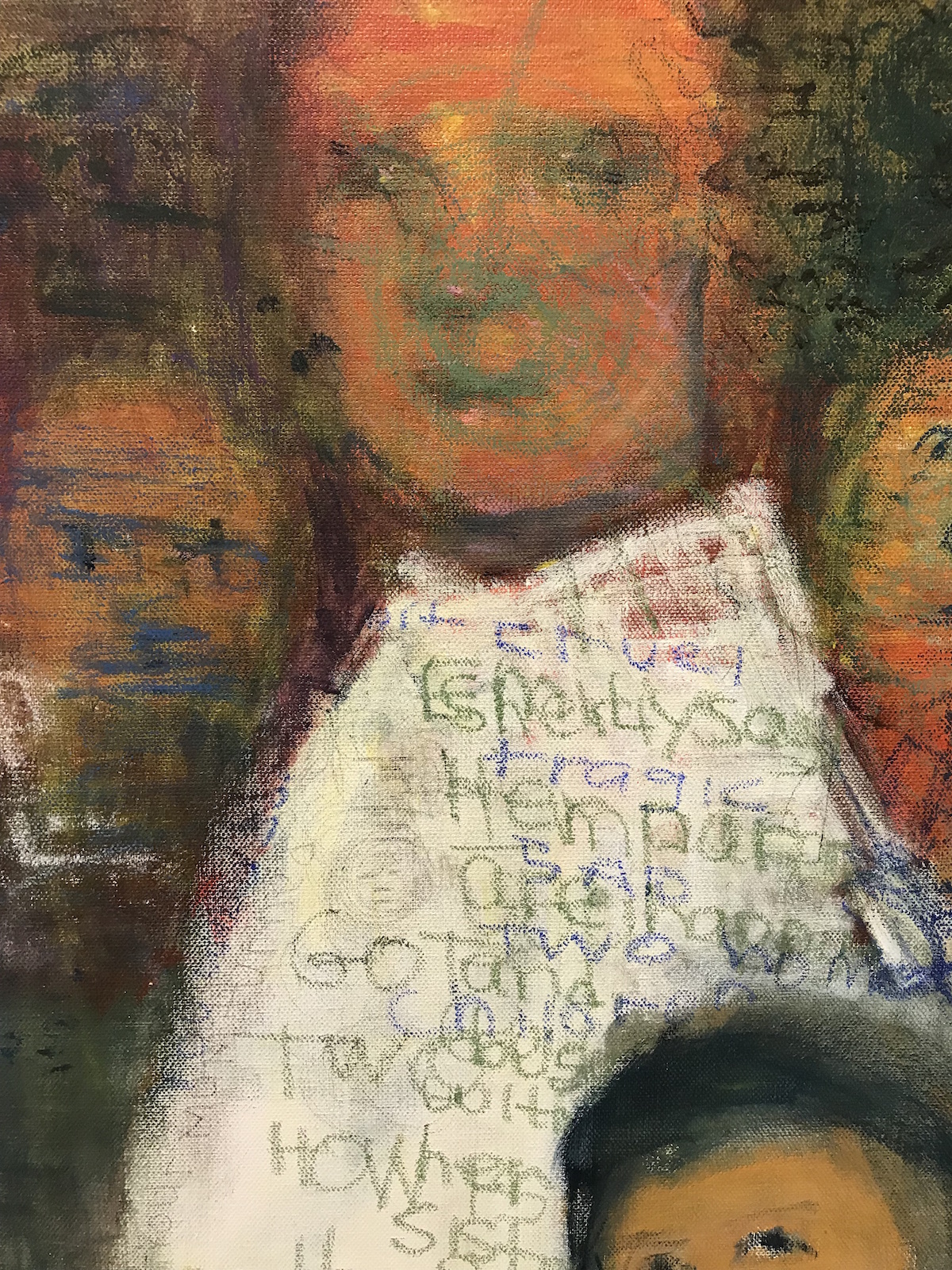

Eunice Park

Eunice Park

A young girl, hastily assembled by blue and brown brushstrokes, glances up wistfully at a ghost-faced, twisting figure wearing cerulean clothing and some kind of loosely coiled head wrap. Behind them looms an enormous chocolate egg form with an aquarium- or TV-like cutout, inside of which various glowing blue marks swim about, some of them swirling around and forming faces. Lurking behind the egg, a third tall figure’s gummy pink clothing and long blue headdress or hair — it’s unclear — somehow lend her an air of superiority. This bewildering scene, titled “Got Myself A Job,” hangs among a series of other delightful and terrifying vignettes painted by Eunice Park.

Park, based in Parkville, makes her debut as a Sondheim finalist this year after a multi-decade break from painting. A few years ago, one of her daughters encouraged her to paint again and bought her some art supplies for Mother’s Day. Drawing from the artist’s dreams, memories, and emotions, the paintings on display here contain something like the deep esoteric symbolism of a Kiki Smith character, the lonesome crowded hubbub of a Bruegel landscape, and the inanimate-objects-are-actually-sentient-beings trope of children’s TV shows and movies.

Though the quality of the paintings is occasionally uneven — like the sketchy flatness of “Then” — they all provoke my desire to wander. Hidden or emerging faces, which almost remain lost amid muddy colors and faint lines, are a motif, used to great effect in “Goethe’s Prometheus.” Dried-blood-colored faces become cliff-like structures on the painting’s sides, a hellish fire erupting between them. Faces materialize from both the flames and the dark, scorched canyon ground — a heretical wasteland that the title also alludes to. Above, in “North Korea on the News,” a tight cluster of men peer out between two tall blue walls, onto a black river where heads and water creatures float, bobbing up from the paint drips. A small child innocently observes the river, too, while the giant face of a woman looks on from behind the men, in wonder, terror, omniscience, or something else entirely. Strange uncertainties pervade Park’s work; political and interior conflicts meld with dreams and fantasies, and none of these pieces becomes more pressing than any other. (Rebekah Kirkman)

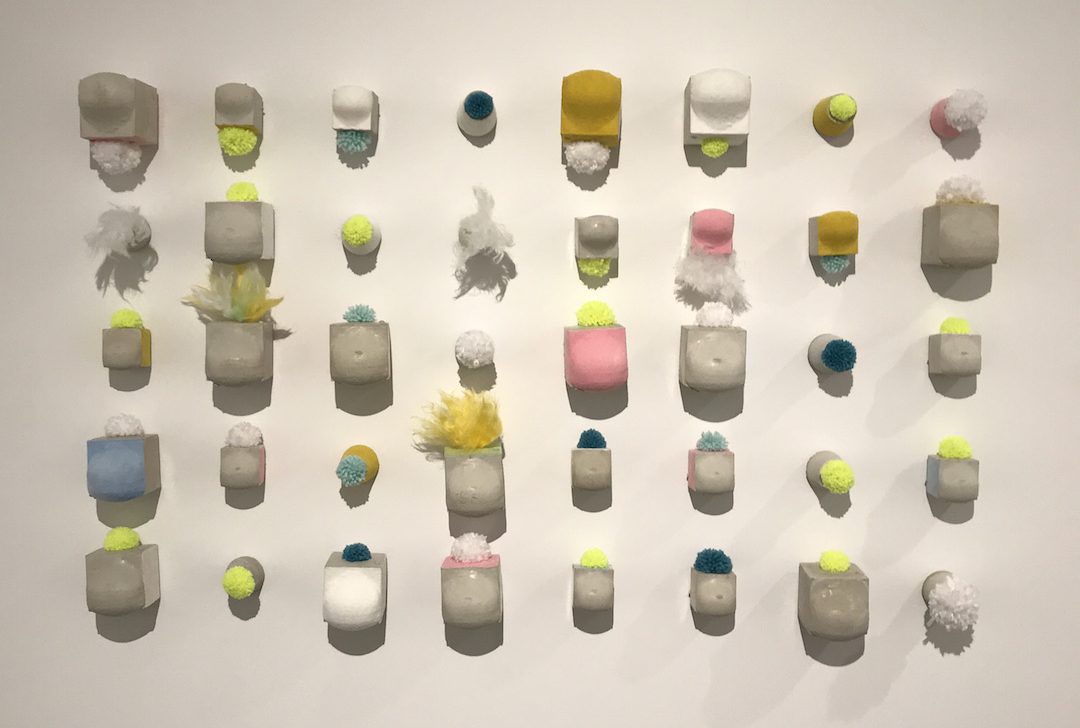

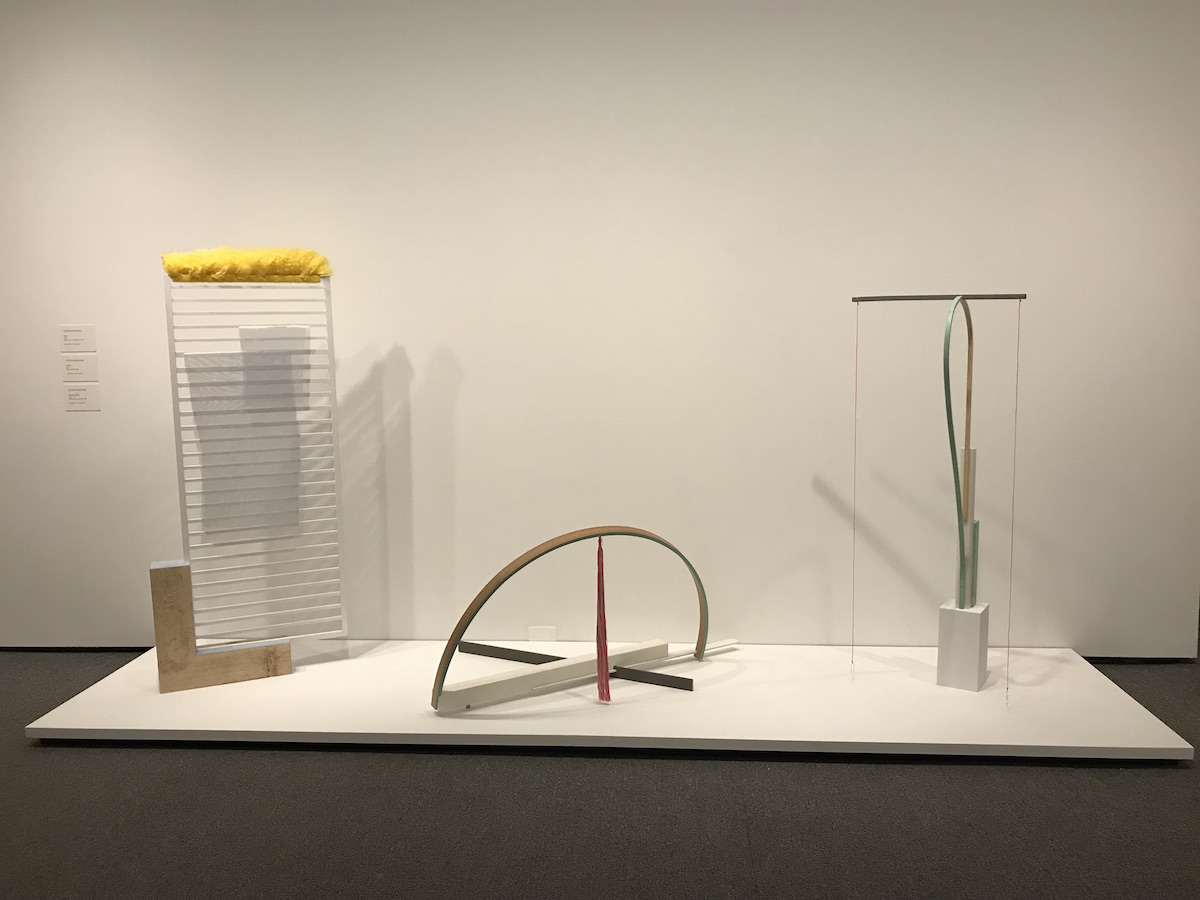

Sutton Demlong

Sutton Demlong

The resemblance of Sutton Demlong’s sculpture “Some Wood, Some Rope, and a Bag of Pom Poms” to a gallows might be bleak if the piece didn’t seem more suited to a preschool play area than an executioner’s scaffold. Hanging from a wooden beam, the two unfortunate souls in this case are a Betty Spaghetti ponytail of long yellow rope and an oversized mesh bag holding a scant handful of pollen-like pom poms. There’s even a bunny tail of sorts: a tiny pink poof stuck where one corner of the wooden base meets the floor.

This is the largest and most commanding of Demlong’s five pieces in the Sondheim exhibition. Dispersed from one room to the next, the Rinehart (MICA) alum’s sculptures position themselves as components of a Rube Goldberg machine whose function is unclear, or characters from an invented alphabet spelling out a meaningless word. In any case, they feel like parts of a whole, though not in the sense that each sculpture is incomplete on its own. They merely feel gestural — more than you might expect from the product of careful joinery and woodwork.

Demlong’s work finds its energy in opposites: hard and soft, straight and curved, rough and polished, blushing pastels and industrial white and gray. It’s a rudimentary formula to achieve pleasing abstraction, but the artist touches on something significant where he bounces between the typically disparate concepts of labor and play to the point that they become nearly indistinguishable. In a trio of smaller sculptures lined against a wall, Demlong imbues meticulous construction with a touch of whimsical precariousness. In “Leaner,” a wooden arch balanced on a thin beam leans forward, seemingly pulled by the weight of a tassel hanging from its center, even though the threads weigh next to nothing and the base of the arch is clearly locked into place.

By creating the illusion of chance and interrupting industrial construction with craft material, Demlong breathes into his objects a certain humanness, a quality that culminates in “Cube Belly Array.” The only piece without a hanging element and the only to appear distinctly figurative, the wall arrangement of 40 miniatures is dedicated to fellow Baltimore-based sculptor Alice Gadzinski for teaching Demlong “how to make pom poms and how to have fun with yarn.” Gadzinski died from breast cancer in March at age 30, leaving behind a portfolio of camp-infused work that glittered in every sense. In Demlong’s tribute, blocks of concrete become bodily by way of swelling, drooping, and playing host to pubic hair-like bursts of colorful yarn. It seems he learned more than just craft from his late friend — at the very least, how to give weight to playfulness, and vice versa. (Maura Callahan)

Stephen Towns

Stephen Towns

This installation feels holy. In a nook whose walls are painted a deep brown, almost black, 13 icon-like portraits depict black men, women, and children wading in the water, enshrined by gold skies and haloes, and locking eyes with the viewer. Titled “A Reflection Eternal,” Stephen Towns’s installation references the historian Marcus Rediker’s “The Slave Ship: A Human History,” a book that zooms in on the immediate, horrific abuses of people taken captive across the Atlantic — rather than taking the long view and analyzing the larger mechanisms that started and sustained the transatlantic slave trade. Described in one review as a “fine-grained account of everyday savagery,” Rediker’s approach seems to differ vastly from Towns’s here. The artist has studied this history and its grisly facts of trauma and exploitation, but has chosen not to display those things in this space, offering stories of resilience, healing, and power instead.

The middle five paintings, from the series “An Offering,” portray black children each with an eclipse-like, gray-black halo, and standing before a quilted body of water. That quilted portion is shaped like a ship’s bow — it also recalls an inverted Gothic cathedral window, which further commands reverence. On the laboriously pieced and stitched water, the children’s reflections appear as radiant, sparkling black silhouettes. Small black hands hold candles (each flame one warm yellow bead) over the water, as if to guide them.

On the left and right walls of the installation are selections from the artist’s “The Gift of Lineage” series, each of which depicts different persons of various ages robed in denim and colorful, patterned garments (fabrics that Towns collected in the U.S. and West Africa). They wade in a body of water and stand watch over sleeping, swaddled babies in baskets, evoking the story of Moses, which wraps up themes of faith, protection, and reunion that are frequently present in Towns’s work, too. Aside from the layered fabric and stitching, the paintings build up dimension with thick, textural waves of gel medium that hold the subjects’ reflections. But before the viewer gets too lost in those waves, they reach the painting’s bottom edge and continue moving onward. (Rebekah Kirkman)

Nakeya Brown

Nakeya Brown

The world has already taken note of Nakeya Brown. The Laurel-based photographer has been interviewed by TIME, New York Magazine, and The Washington Post, and has exhibited her work in several states and overseas. It’s no surprise that Brown’s explorations of black womanhood and hair care resonate globally, but it’s a wonder she hasn’t developed a stronger presence here in Baltimore prior to her selection as a 2018 Sondheim finalist — especially in a major American city with no shortage of women reflected in her work.

At first blush, Brown’s carefully staged, pastel-toned photographs appear void of the intimacy that comes to mind when thinking about the community around black hair care and the deeply personal connection between hair and identity. She keeps her viewers at a distance: The artist turns away from the camera in “Self Portrait in Shower Cap” so that her face is hidden. Her still life compositions of hair products and appliances have the sterilized feel of infomercials. Even the models in the four portraits in the series “The Refutation of Good Hair” return the camera’s gaze with a low key “fuck you” glare as they stuff their mouths with synthetic hair.

Perhaps that cool remove is an attempt to make room where there frequently is none. The world holds a magnifying glass to the hair of black women: scrutinizing it, policing it, insisting that it conform to impossible (read: white) standards and then criticizing women for spending too much time and money to meet those demands. Brown offers the gift of space, in effect endowing her subjects — and viewers — with a sense of autonomy.

In “The Art of Sealing Ends (Part I),” an image of a figure shrouded by long box braids, “Art” is not simply an allusion to complexity and craft, as it is frequently used in reference guides to elevate process. The labor, time, and precision that go into black hair care are self-evident; Brown positions black hair as something more. Spilling down from the figure’s stooped head and into the rosy pink bowl, the hair becomes a physical monolith — on what appears to be a stone pedestal, no less. “Art” here is more like the “art” of marble statues: admired for their craft, but more importantly for the stories they tell. (Maura Callahan)

Nate Larson

Nate Larson

Three glass-block windows on the side of a Dollar General in Olney, Illinois, glow red, white — or rather a yellowed, dirtied, aged white — and blue. Olney was one stop for photographer Nate Larson’s ongoing project to document “centroid” towns, points that have been designated by the Census Bureau as the “mean center of population in the United States.” Since the very first one was located in Chestertown, Maryland, in 1790, the points, of which there have been 25 to date, have moved steadily southwest over the years. The centroid is hypothetical, based on a physical and geographical impossibility: if all persons tallied in the census were weighted equally across an imaginary, flat map, the centroid would mark the point where this map would balance perfectly.

Larson has been documenting and researching these towns since 2014, partly to record and understand something about the American political hellscape in which so many of us are trying to live. The documentarian angle lets the photos’ messaging remain somewhat frustratingly subtle.

A surreal picture of broken industry, “Site of the Former Shoe Company, De Soto, Missouri” depicts mountains of telephones, disconnected from their cords and off their hooks, pile up inside of a decrepit warehouse, surrounded by fallen beams and meaty, pink insulation innards. The antiquated, useless phones signal the absurdity of waste; the mismatch between the photo’s title and subject suggest the ongoing cycles of stagnation, change and reuse in industrial spaces.

Three out of the four small photos of signs from Missouri, Indiana, and Maryland seem like responses to the first one, which advocates for Christianity and exhorts its viewer to “THINK AMERICAN” and “SPEAK ENGLISH.” The one to its right features a hand-scrawled version of the Gettysburg Address taped to a window. Another sign, on cardboard tacked to the side of a porch, champions love in spite of an “evil and unloving society,” and the fourth photo is of a kind-hearted, if blasé, church marquee, “DO UNTO OTHERS AS THOUGH YOU WERE THE OTHERS.”

A few of Larson’s portraits of residents, which are also portraits of places, are particularly striking — like these two side-by-side portraits of Juanita from De Soto, Missouri, and Ron of Fenton, Missouri. Ron hangs out of a doorway, staring straight into the camera, stepping into an entryway or a mudroom. Larson must have taken the photo through a glass door; Ron’s worn, pinkish face refracts through it and reappears on the image’s right side, this time seeming less confrontational and more weary or concerned. In the other photo Juanita, a tiny old woman in a lilac T-shirt, stands behind a cash register, surrounded by various sun-bleached signs advertising the prices of the shop’s chicken gizzards, livers, and “drummies.” Juanita takes up so little space in that composition, I find myself searching every detail around her — trying to comprehend less of the individual folks photographed and more of the environment and the structures that composed them. (Rebekah Kirkman)

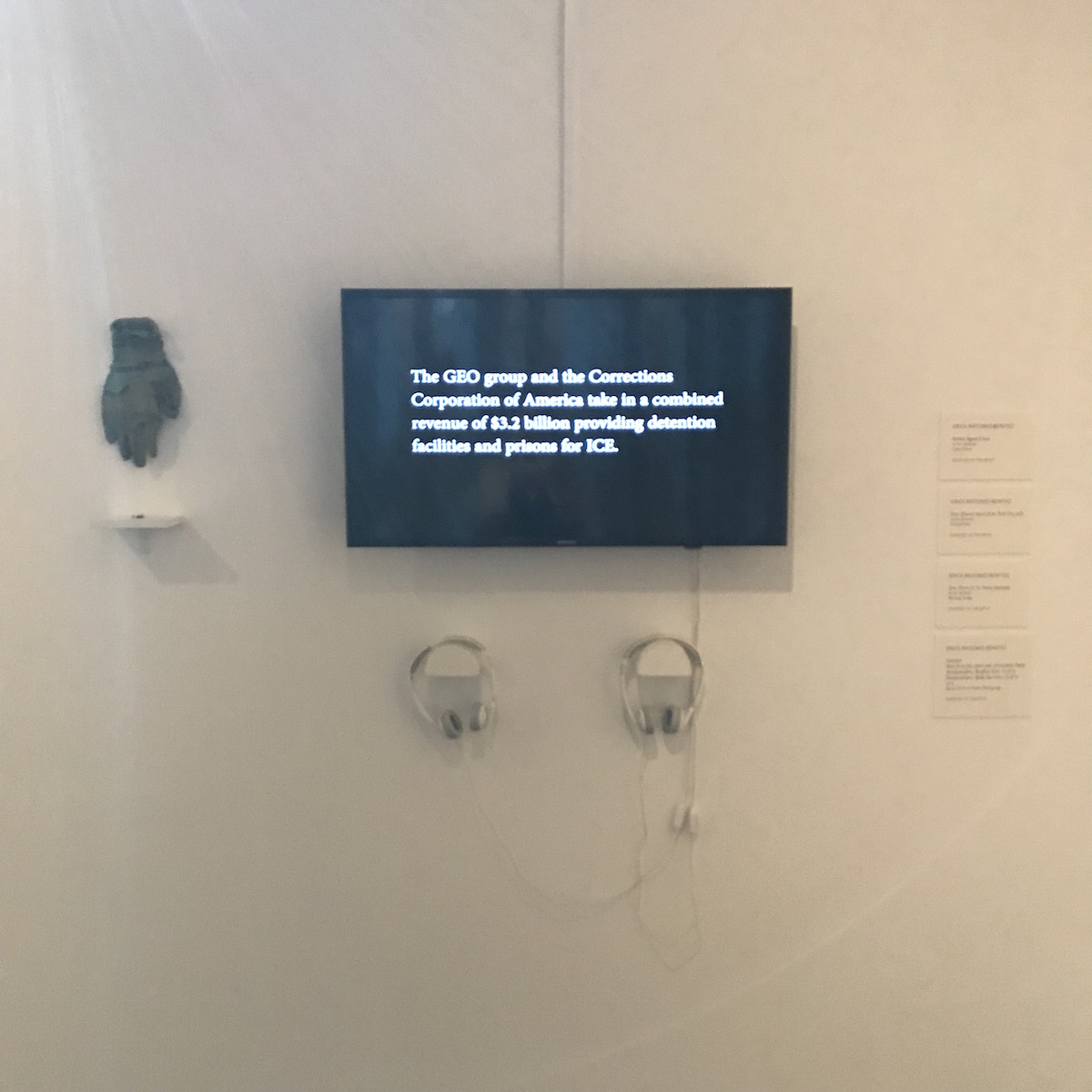

Erick Antonio Benitez

Erick Antonio Benitez

The scribble of barbed wire hung at the approximate height of a detention wall is surprisingly elegant. In a dim room under gallery lights, it creates a prickly calligraphy that is illegible, yet easy to comprehend. The low lighting adds to a sense of containment and illuminates a few glowing screens, small photos and objects spotlit on the wall, and functions as an informal theater for an installation that fills one large wall, floor-to-ceiling, with video projected over sparse wooden beams.

The misery of those detained in US border facilities is consistently palpable in the sculptural, video, and photographic installation of Erick Antonio Benitez. Unlike the horrific news cycle of detention and protest, which elicits immediate and passionate reactions, a sense of human tragedy unfolds much more slowly and intimately in Benitez’s work, where you are allowed to focus on the objects left behind by humans caught in the vicious cycle of illegal immigration in the US. A sense of empathy grows slowly and steadily the more time you spend in the space. In an America becoming synonymous with the egregious abuse and cruel separation of families, especially children taken from their parents in US detention centers, Benitez’s work grows more potent.

This work is not a new project for the artist. Over the past few years, especially since receiving a Rubys Grant, Benitez has traveled to the US – Mexico border to document the conditions in detention facilities. Although it’s no less powerful than a journalist who collects stories and attempts to share them with as little bias as possible, Benitez sifts though this content as a visual artist. As a result ordinary objects like pink detention towels (meant to emasculate the men forced to use them) or plastic personal objects abandoned in the sandy desert take on metaphoric, almost iconic, meaning. Benitez’s photos tell the story of barriers and walls, offering scant views into spaces that tell incomplete stories, while his video tells complete narratives on TV monitors with headphones. Objects like worn gloves and a pair of dice offer clues of the people who took on personal risk to cross the border and come to America, while more abstract video footage is projected wall-sized onto the wooden makeshift screen structure.

Benitez’s work allows a viewer to sift through the clues the way a detective—or an artist—combines mysterious details together into a composite, but still incomplete, story. There’s a sense of restraint in his storytelling, that the artist is giving us just enough essential clues to puzzle it out. In this measured way, the artist builds a sense of conviction, which can only be gained by actively engaging with the sights, sounds, and objects that Benitez himself experienced. (Cara Ober)