Ronald Jackson’s Profiles of Color III: Fabric, Face and Form at Galerie Myrtis: An Interview by Angela N. Carroll

The contemporary art world is experiencing a renaissance in Black portraiture. A new generation of master realist painters like Kehinde Wiley, T. Eliott Mansa, Jas Knight and Ronald Jackson build upon a foundation laid by earlier figurative artists like Charles White, Augusta Savage, John Biggers, and Elizabeth Catlett. Their figurations not only visualized black identities with agency and humanity, but exuberantly revised histories of portraiture that uniformly presented non-white representations as submissive props. In those historical portraits, Black subjects were often painted in acts of service and relegated to the background of elaborate renderings of white nobility. Jackson’s portraits counter these histories by rendering Black subjects in imaginative and layered narratives that he calls “collage portraits” or oil paintings that incorporate stylistic approaches of collage.

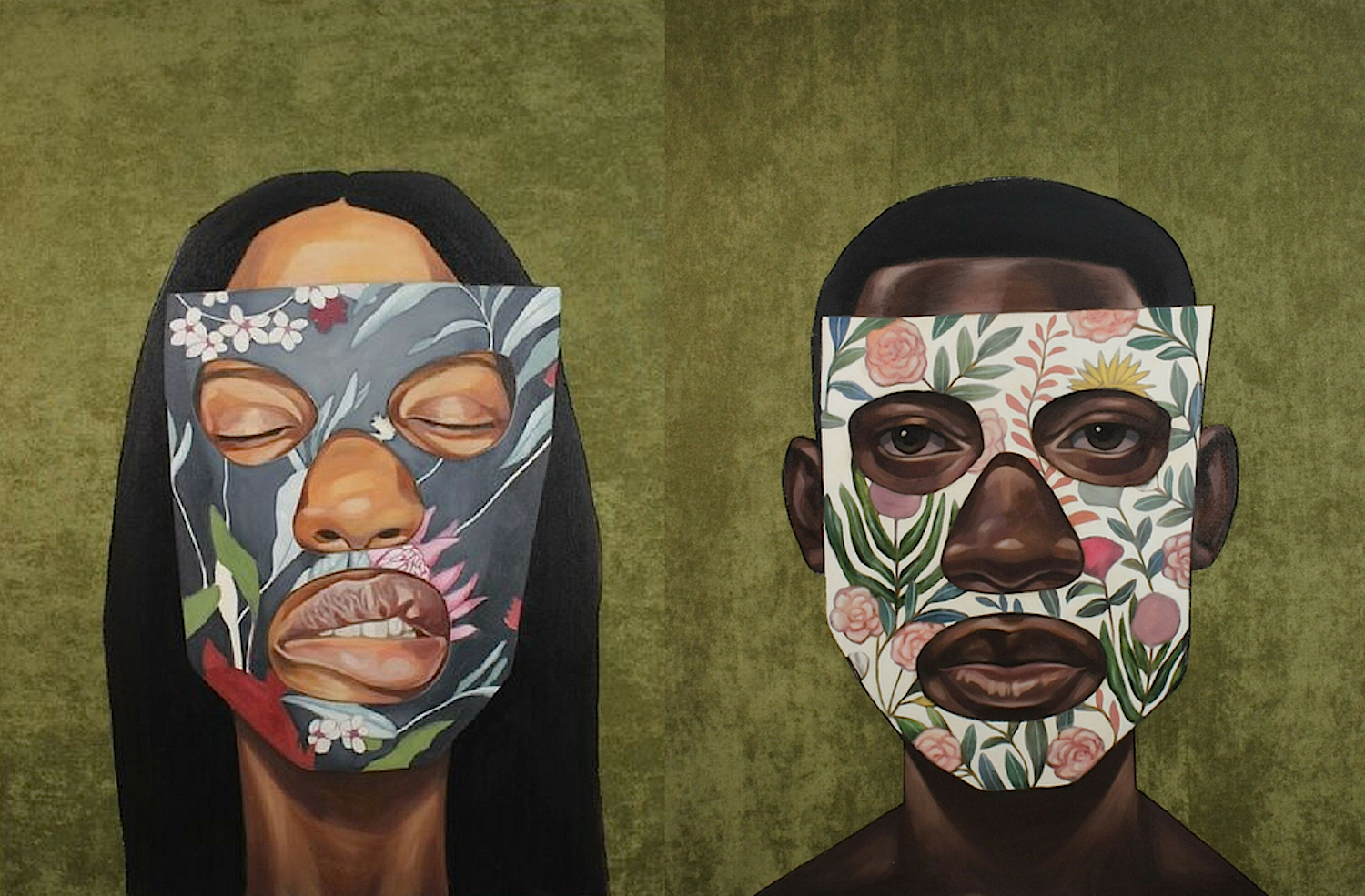

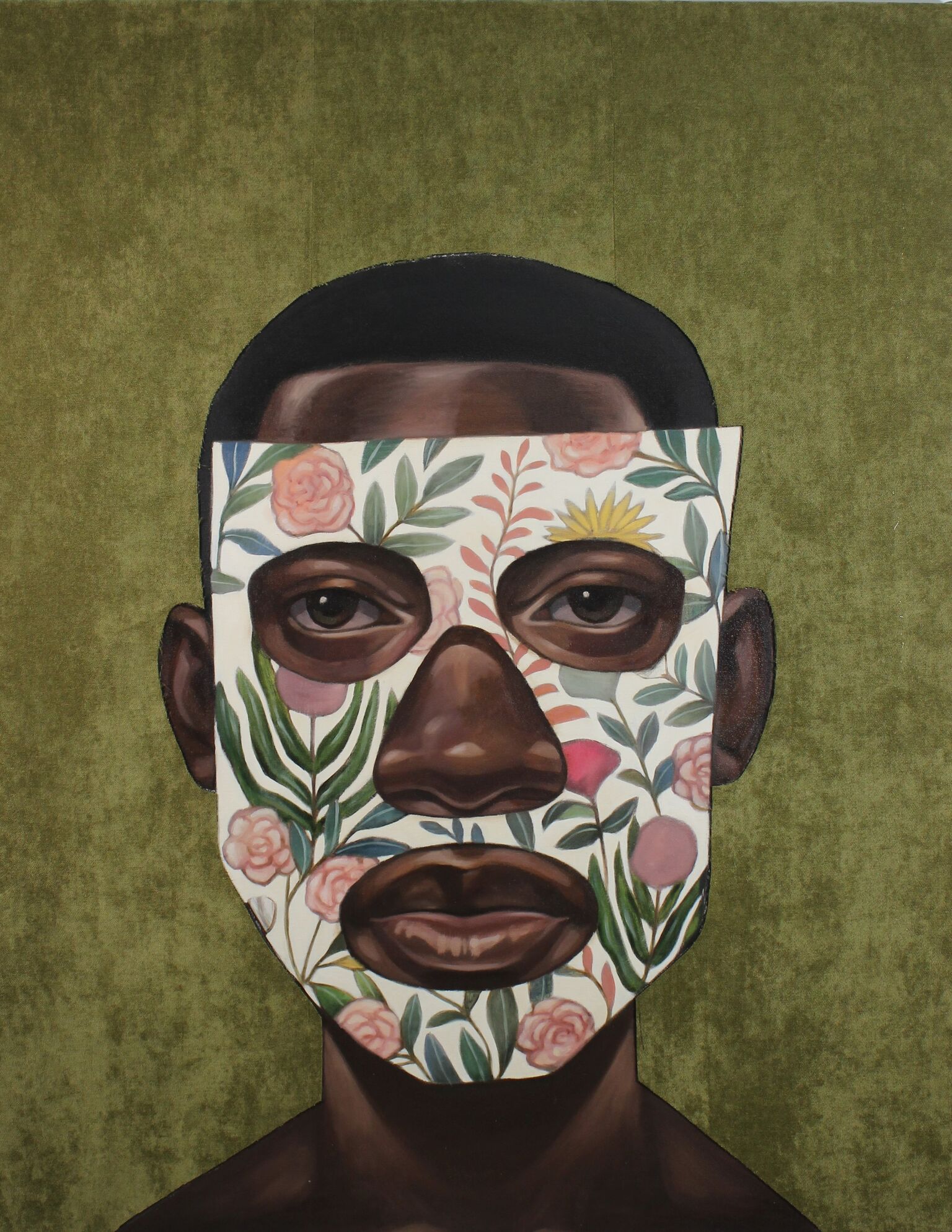

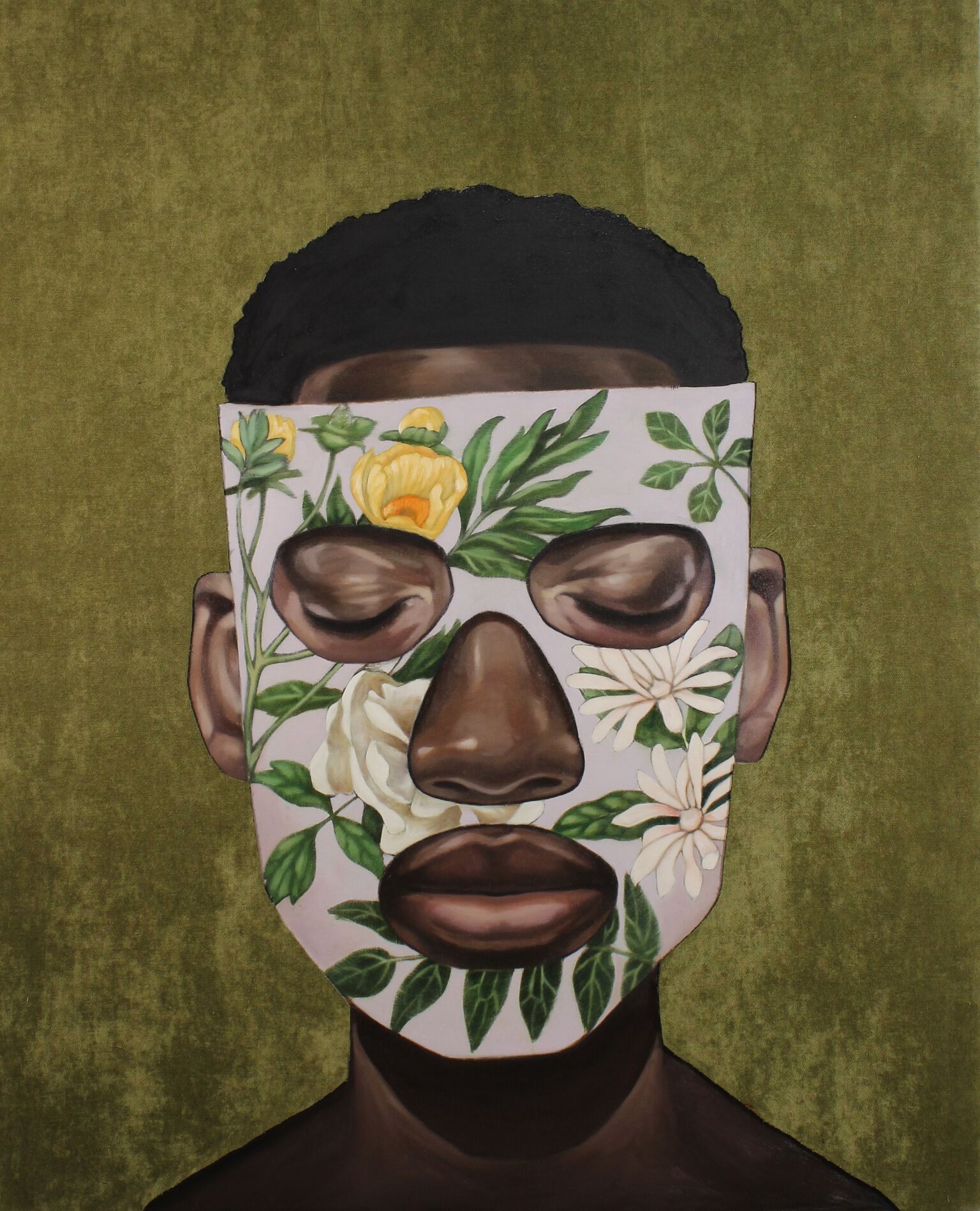

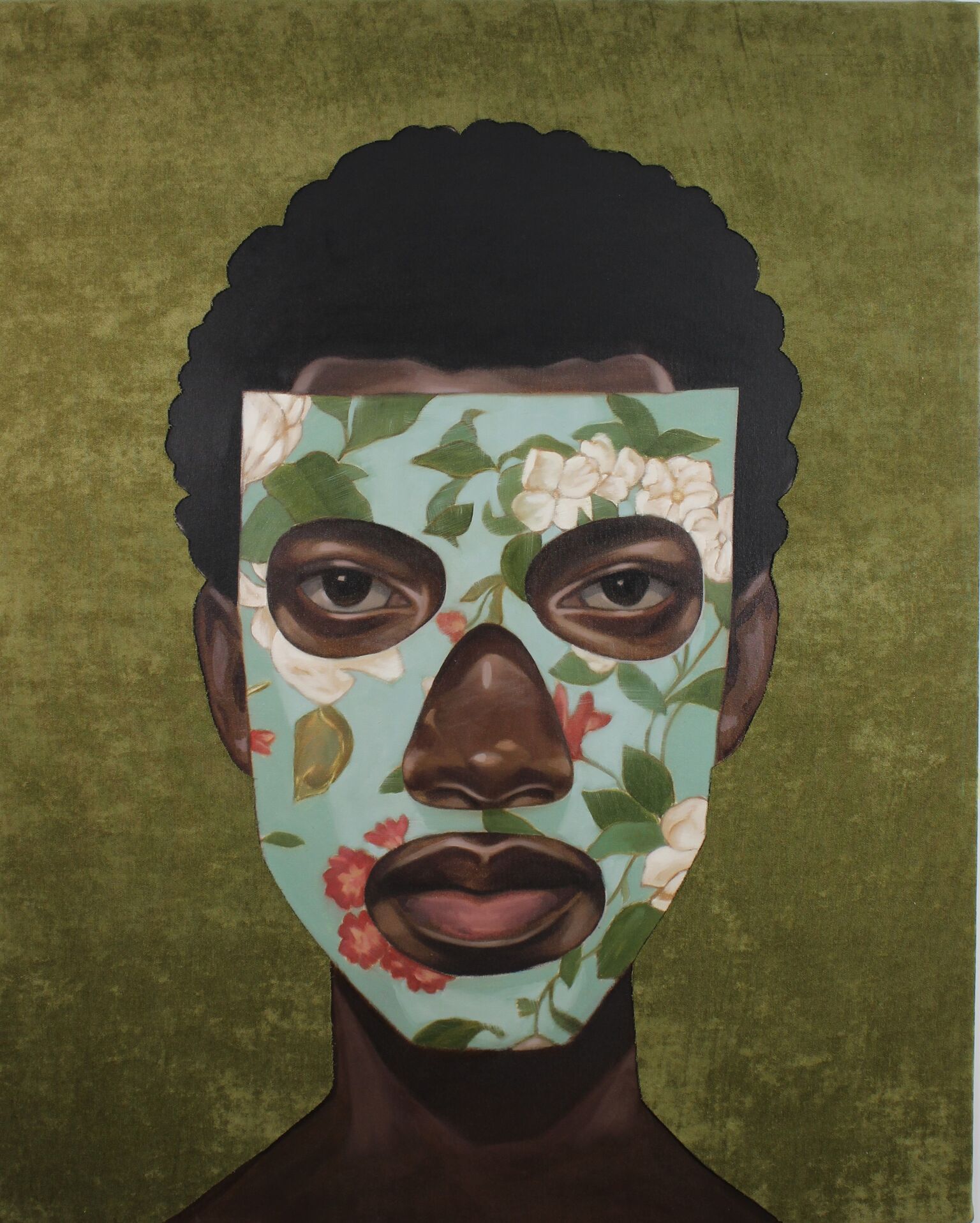

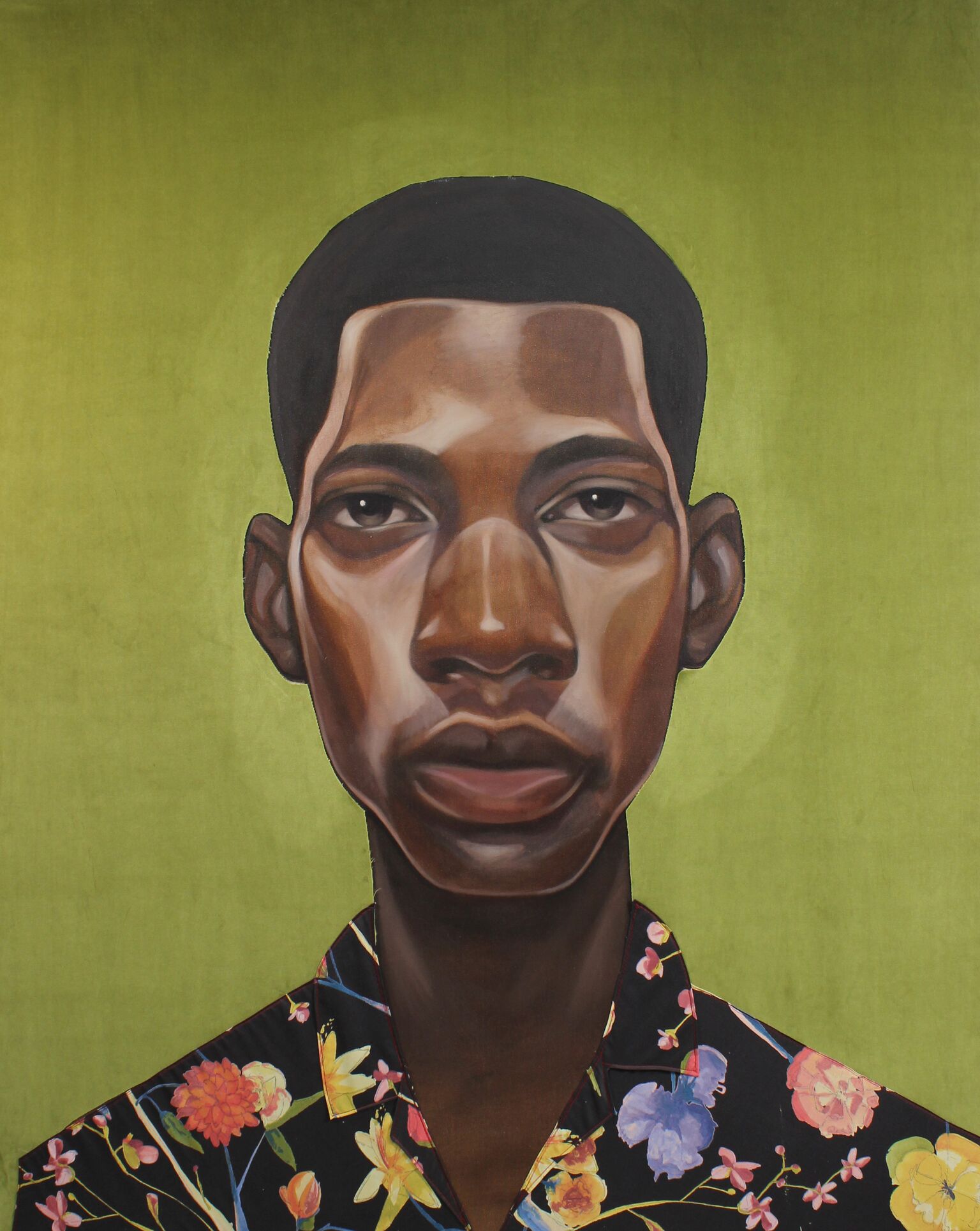

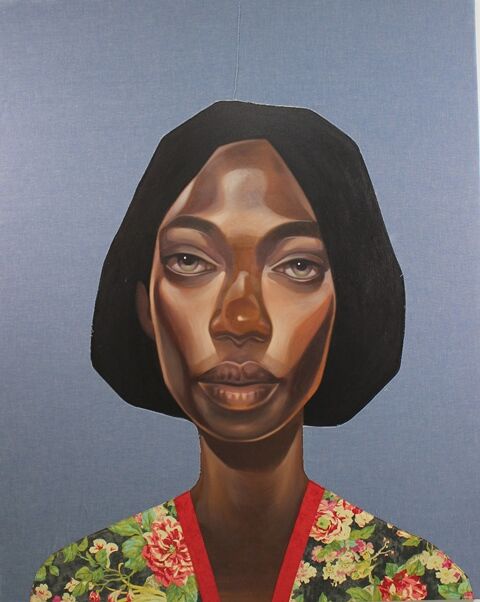

Profiles of Color III: Fabric, Face, & Form, Ronald Jackson’s latest collection currently exhibited at Galerie Myrtis, references Arkansas rural culture and violent racist history, the fantastical elements of Magical Realism and the emotional and psychological tropes of Romanticism to offer a stunning appraisal of Black aesthetics. Floral and geometric prints and vibrant fabrics are harmoniously incorporated in large expressive oil paintings.

Masked and fashion forward subjects confront your gaze, peer into the heart of the matter with unabashed directness, as if they were proclaiming, “You will see me and know that I am beautiful, powerful, and worthy of representation.” The collection is breathtaking, incredibly inspiring, and exquisitely executed.

Ronald and I conducted a FaceTime interview to discuss his process, the characters he depicts, and the importance of Black figuration.

Angela N. Carroll: You are the youngest of 11 kids and grew up in rural Arkansas. So many of the narratives you depict are of rural scenes or everyday southern folks. The portraits and landscapes also have a palpable dreamy quality that feels filmic or like a memory, especially works like Self Portrait as a Horse or Remember the Sounds of Home. What influence has magical realism and growing up in Arkansas had on your work?

Ronald Jackson: I kept being drawn to certain images, particularly Robert Vickrey, he’s an artist who has a book about magical realism. I discovered that genre which was originally a literary genre through Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who wrote the novel 100 Years of Solitude. That’s an a interesting read to kind of see the elements of how that fantastical aspect is handled as a genre. But as I studied other work and observed other work I found that this is the type of expression that I desire to present in my work.

As far as my upbringing, and how it effects my art work, it’s something that’s very unconscious. I grew up in a rural farm community, and I guess it comes across not intentionally but a lot of times I work on pieces, several pieces at a time usually, and they are hanging in up in my studio, and I’m sitting back in different stages, and just observing and studying and trying to get direction about where I’m going with the work.

A lot of times I am discovering things about myself through the work and it’s been an interesting practice. In my narrative work I desire to deal with ideas, stories or ideas through figurative imagery and I choose to place them in an environment that I create and the environment is usually organic.

I was most impressed by the characters you create, the realism of their expressions and the directness of their gaze. Are the people in your portraits inspired by living muses, memories, or lived experiences or do they all stem from your imagination?

My portraits are almost exclusively images of people that I have made up. I may use some references here and there, but it usually starts and ends just from my imagination and artistic freedom. Then I would say, my main focus is design in the narrative work where I can use figuration and environment to deal with ideas. But when I’m doing the portraiture, as I did here, I decided to use the titles to identify with some things of my past and a number of the pieces were associated with some of the small towns and unincorporated townships or communities near where I grew up. And in some of those areas there is some significant history.

There’s a piece that’s called “No One Knows Elaine,” and there’s another piece that’s titled “Elaine’s Girls Don’t Cry.” After WWI there is an incident that occurred in the small town of Elaine… The Black sharecroppers were organizing, and it was attempted to be stopped. A white man ended up getting killed, and after that point there was a mob of locals, when I say locals I mean the white population, they came from counties, from across the river, from Mississippi, and truckloads began going through and just pillaging the communities of the Blacks and it was open season to just target and violate or do whatever to the black community. The event is known as The Elaine Massacre.

In portraiture I like for the viewer to contemplate about the experiences of the person that they are looking at. I try to present them in an intimate setting or intimate way. They are usually not smiling or in some way that a person would be engaged with another person. You are finding them in a private place. For me, I feel most people when they’re in their private place, no ones around they are not interacting, they don’t have the facade of a grin or a smile that’s an emotion that’s associated with socializing and interacting with people. But when you see them without an outward expression it draws you in to ponder what’s going on in the inside, who they are, and their experiences, and you start to look into their eyes and contemplate that.

My intent [is to] allow [the portraits] to be a reflective experience with the person looking at the portrait. And those [portraits] can represent many people. They are usually of no one in particular, but I guess a lot of the features that I choose to emphasize in my renderings are features that I’m familiar with and they usually come out to look like someone that I’m familiar with or people can relate to.

I was especially drawn to the paintings “The Envy of the Dreamer Joseph” and “A Veil of Bitter Songs.” Those narratives have a bold graphic quality and close attention to structure. I read that you briefly studied architecture. Does architecture influence the way you approach your collage portraits?

Many years ago I was in an architecture program. That was the artistic direction that I figured I would explore and actually I became exposed to fine art after that. I realized that architecture really wasn’t what I wanted to pursue. I realize that its more about observing things around us, whether its architecture, textures and things, or how colors collaborate together, it’s all about the observation of things that are around us. I wouldn’t specifically say that architecture itself has an influence in my work, it’s just part of that exploration of me trying to find which avenue that I’m going to express my natural artistic insight. That was actually the starting point which led me to other avenues.

In your short essay The Romanticization of the Black and Brown, you note “I find the process of manipulating paint on the canvas as being more critical than the materialization of the image.” Your images are so specific: black portraits whose gaze demands the full attention of the viewer. Can you talk about how this process of manipulation lends itself to the creation of portraits?

It’s important as an artist, at least for me, to understand, I wouldn’t say have a relationship with, but understand the material that you are working with, how it works in various ways, and various consistencies. As a painter there is a lot that I’ve learned over the years; various consistencies that work with oil paint, choosing the type of brush. Even in relation to the fabric, I purchased a large piece of upholstery fabric [and] I was so moved by the feel of it and how it looked that I draped it on my wall, and it gave a different feeling to the room. Not just the experience of looking at the fabric, but it changed the environment of the room. And that’s a quality that the material gave to the observing experience.

Likewise, my experience of manipulating the paint with different colors and layers overlapping, I am learning throughout the process about what my material can do. You hear the saying it’s the journey not the destination, it’s the process and there’s so much to learn about the material that you are using that shouldn’t be overlooked.

I was pleasantly surprised to view your self-portrait series, “Self Portrait as a Horse” and “Self Portrait as a Horse #2 (black horse).” These works are the most “magical” because of the oddity of subjects and objects, and lack of humanoid figurations. What inspired the creation of these paintings?

I am anxious to continue along those lines and subject matter dealing a little more with symbolism. It’s a way for me to address the same ideas by using different objects and replacing some of the things we are more familiar with seeing. There’s a group of works, five that I’ve created so far. I wanted to continue the series surrounding the idea of romanticism, or the romanticization of Black and Brown. I created those works when I was reading and listening to documentaries on the romantic art period. How they address ideas with an over emphasis to the point that they over glamorize to make the point. [In] this series I was presenting the idea of how being black can be over glamorized as far as, some of the black artists, athletes, entertainers but they are personalities to look up to desire to be they but they still are just black and brown people that share the common thread of identity and who we are and what our history identifies us with.

The painting of the horses are representations of black and brown people; there’s a black horse and a brown horse. Both are being celebrated in some way. One has mylar balloons that are deflated and floating around the horse. The other one has origami. Substitution is something that I’m looking to work with more.

Regarding the horses being called self-portraits, I started identifying horses similar to Black and Brown cultures around the world. Horses have been used to serve the wealthy and those who are in power and that kind of parallel at least to a certain extent of time, our history, most Black and Brown cultures have experienced, have been used to serve the powerful.

Well-to-do people have nice horses. Even reflecting the times of slavery in our country, the biggest part of the population didn’t not own slaves, there were those privileged ones that were able to show their affluence by the Black and Brown humans that they owned. Then again, horces are looked at as prized possessions. They are paraded for their beauty or strength or athleticism. I am making just with the title alone, comparisons to how black and brown people have been used throughout history. Because I have a background in the military, I was also relating to how horses throughout history have served, whether for noble cause or deviant purposes, they have served the like.

Do you consider your incorporation of fabric to be an extension of your painting process? Was fabric always a part of your painting process?

That’s something that I just happened to fall into five years ago, and for me, particularly the fabric is kind of a pseudo collage practice, it’s a part of my exploration of being an artist.

Learning to sew is adding another tool to my toolbox, giving me another way to express ideas I have. It’s about exploration. With the fabric, about five years back, I was preparing for a solo show in Richmond VA, I had a number of paintings that I was completing and at that time I really saw myself less as an artist and more as a painter. I was coming close to the time of the show and I was running behind. One thing that I pretty much have always been able to do is paint faces, out of my head or of people, but I didn’t want to be characterized as a portrait artist. I wanted to find ways to be creative in my portraiture. With the deadline coming up I chose to just start painting a number of faces. Not knowing what I was going to do with them. These were portraits that just came out of my head and then there’s the idea of what environment do I place them in?

I’ve always been kind of opposed to just painting a person and then just coloring the background a solid color. Just presenting it like that. I’ve always had an idea of making it a little more interesting. Putting them in a different environment. I decided to take some fabric and place it up against the negative space around the paintings. I would take decorative piece that had patterns on it, different colors and it started to give different feelings to the portrait. Depending on the piece that I placed against the portrait. That is something that I do with painting, I paint some part and I don’t like it I change the color or whatever. With the fabric I was able to immediately see the response that the image would have by placing different components next to it. That was quite intriguing to me and it also allowed me to finish the work much quicker.

The series is called Portraits of Color III – Fabric, Face & Form. Is this a continuation an earlier body of works?

This is the third iteration of the Profiles of Color series about how people of color connect with colors and patterns –our ancestry. You look at some of the fashion choices and the clothing they wear in Africa it is a fully intentional desire to show color and patterns. I see that as a reflection of who they are and who we are as people. Even where I grew up in the south you would see that same thing. You would go to church and see this brother in a crazy green or burgundy three-piece-suit. There is something about that that you don’t see in a lot of cultures. I have spent time overseas and in Europe and there are cultures like in Belgium where it is amazing how they are drawn to gray and black and stone colors. It’s simply incredible to see that. Especially in the winter but the summer doesn’t bring too much color out.

The work started small at 16×16. Then the second iteration of Profiles of Color moved to 24×24 it has come to the point where we are today which is using almost exclusively fabric and heavier weight fabric and much larger scale.

Some of your portraits like “A Study of a Black Man’s Soul,” “Elaine’s Girls Don’t Cry,” or “A Prayer for Saint Charles” are masked. Does masquerade influence the work or are you continuing to explore form, color and pattern through the incorporation of masks?

I started with large portraits that don’t have masks. There is a sense of mundaneness with just making a simple portrait. The large ones are not simple because they are so large and incorporate fabric. I moved from that to the masked pieces because I didn’t want to continue just a collection of heads. For me I’m always thinking about a creative way of exploring an idea.

A number of my paintings incorporate foliage, or flowers, branch with leaves, particularly in the hands of young black men, [they will] have something that is considered non-threatening like rendering an extended olive branch as something that no one would find threatening in the hands of a young black man. Masks have two dual purposes; to hide/conceal or project an ideal. With the mask, I thought it would be an interesting concept to explore and present to the viewer who they are looking at and potentially the message that the portrait is giving to the viewer.

When dealing with portraiture I’m looking for the viewer to self-reflect, to have an inner reflection, [that is] facilitated by the painting, or the portrait that they are looking at. With the floral, foliage, flowers on the masks it’s a symbol for me of presenting yourself in a nonthreatening way, wishing the viewer to see you as desirable.

The idea with flowers, I freely use them not as a source of femininity, I use them with men and women. No one has a negative disposition towards flowers, flowers are generally welcoming. That’s the desire of projecting the person behind the mask in that way. Regardless of experiences they they’ve had or whoever they are, giving them that benefit of a doubt that they are desirable, harmless, and beautiful. Because some people cannot get past the outward appearance to consider the beauty of a person’s heart.

Profiles of Color III – Fabric, Face & Form, a solo exhibition by Ronald Jackson is on display June 30th – July 28th at Galerie Myrtis. Visit GalerieMyrtis.com for details.