The Baltimore Museum of Art will deepen its holdings of works by women and artists of color using funds from sales of seven redundant works.

*Published at Hyperallergic on May 8, 2018

by Cara Ober

Joyce J. Scott: Kickin’ it with the Old Masters at the BMA in 2000, curated by George Ciscle and MICA EDS

Joyce J. Scott: Kickin’ it with the Old Masters at the BMA in 2000, curated by George Ciscle and MICA EDS

BALTIMORE — “A museum is a place where racism and sexism is on full display,” said artist Shinique Smith. “You can see this in any institution in any part of the world.” Smith, an internationally known painter and sculptor based in New York and Los Angeles, who has works in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Rubell Collection, the Whitney Museum, and numerous others, grew up in Baltimore and recalled the profound influence of the Baltimore Museum of Art on her development as an artist. “When I grew up, there was no contemporary wing at the BMA, so I grew up looking at Henri Matisse and Romare Bearden there.” When she grew older and became a student at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), she recalled seeing Robert Rauschenberg’s “Canyon” at the BMA as a primary influence over her own abstract and bundled fiber works.

These recollections were part of a series of conversations I had recently with artists, curators, and museum professionals, after the Baltimore Museum of Art announced last month that it would be diversifying its collection to enhance visitor experience through recent acquisitions of works by women and artists of color and by deaccessioning repetitive works. The announcement read:

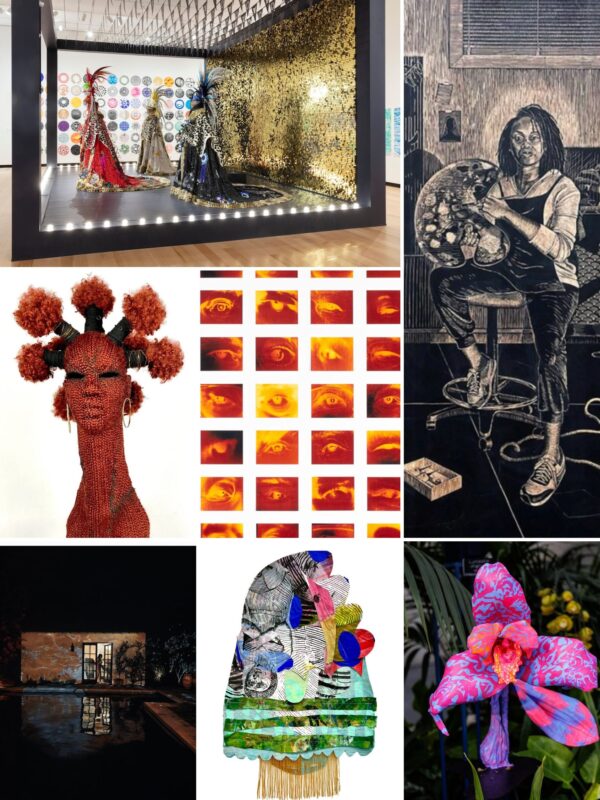

The funds raised will be used exclusively for the acquisition of works created from 1943 or later, allowing the museum to strengthen and fill gaps within its collection. During the same meeting, the trustees approved the acquisition of nine works by contemporary artists Mark Bradford, Zanele Muholi, Trevor Paglen, John T. Scott, Sara VanDerBeek, and Jack Whitten, several of which are the first by the artist to enter the collection.

The seven works marked for deaccession will be sold at auction or in private sales. They include a Franz Kline, two by Kenneth Noland, a Jules Olitski, a Rauschenberg, and two pieces by Andy Warhol. The museum said that it has followed the guidelines established by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD).

“These men that we are talking about deaccessioning, I looked at them growing up because I had to,” Smith recalled. “In terms of growing up in the art world, I had to do extra research beyond the museum to find artists of color. This move is a correction and, for the demographics in Baltimore, it makes sense. The museum should be for everybody and should reflect the diversity of Baltimore.”

I agree with Smith. When I read the release, I thought very little about it initially because our cultural institutions, especially museums, are obviously lagging in their missions to present and collect the most significant works of art of our time. Why wouldn’t you sell off redundant works, deemed to be lesser in value than similar works in the museum holdings, in order to buy others by underrepresented contemporary artists?

Smith’s statement reinforced my own experiences with the BMA over the past 20 years. Until this past year, the museum had hosted just one major, ticketed exhibition with a catalogue devoted to a woman or an artist of color — Joyce J. Scott: Kickin’ it with the Old Masters in 2000. In a city that is more than 60% African American, the news that the museum will sell redundant works by white men to purchase new works by women and artists of color is a no-brainer. For me, the more interesting story is a broader move by the museum, which has embraced a number of artists of color in the past year, hosting exhibits by Senga Negudi, Meleko Megosi, Al Loving, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Stephen Towns, and a Jack Whitten exhibition that will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with an Amy Sherald exhibition in the works for 2020. However, the news quickly ignited controversy and sparked discussions of widespread changes in museum culture that should be, in my view, ubiquitous.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby with Cara Ober at the BMA in 2018

Njideka Akunyili Crosby with Cara Ober at the BMA in 2018

* * *

After a Baltimore Sun article that explicitly linked the upcoming sale of art by white men with the purchase of works by women and people of color, some critics took it further, likening the practice to historical affirmative action at its worst. In a Baltimore Sun op-ed, David Maril, president of the Herman Maril Foundation and the artist’s son, wrote:

The use of deaccession — selling seven paintings to achieve this goal of supporting local and regional contemporary art — is a horrendous decision. What is especially troubling is the somewhat jubilant and self-righteous tone surrounding what the museum is doing. Never mind the positive a spin the BMA puts on this decision such as insisting it’s conducting routine museum business. Nothing could be further from reality.

Tyler Green, the producer and host of the Modern Art Notes Podcast, tweeted his concern that the BMA was not following AAM guidelines regarding deaccessioning, writing: “It’s by a man, so we’ll sell it even tho it’s a great artwork.” A subsequent tweet read: “I’d like to know where in AAM’s guidelines it says that deaccessioning motivated by gender is a best or even sanctioned practice.” Though the BMA’s press release announcing the deaccessioning doesn’t offer much insight into the process that led to the selection of the seven works to be sold, neither it nor the Baltimore Sun‘s report suggests that the motivation was the artists’ gender. Museum staff “discovered areas of repetition” in the collection, the BMA announcement states, and “in each case, the museum currently holds stronger works by the same artist, and in some cases, more significant versions from the same series or stage of the artist’s career.”

“Deaccessions are often controversial, but the changes they bring can be good,” said Taína Caragol, curator of Latino art and history at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. “The Baltimore Sun reported that the BMA has 90 works by Andy Warhol, two dozen by Rauschenberg, and about a dozen by Kline. The museum’s leadership has studied the issue carefully for a year and a consensus has been reached with the staff and community members that allows for more, valued artists to have a place in their collection. As curators and museum professionals, we have to keep questioning the canon, and with this let it evolve and welcome new voices. We want to see new artworks by both historic and new artists who should be better known. Deaccessioning these works creates space and raises funds for unseen artworks, without diminishing the BMA’s collection of postwar art.”

Read the entire article at Hyperallergic.