There’s something innately tender that drifts through the current exhibition A Big Toe Touches A Green Tomato at Baltimore’s newest curatorial platform, Resort. The exhibition functions as a collaboration between artists Roxana Azar and Ginevra Shay and proposes a way of belonging to the world that is at once mindful and attentive. Together the artists speak to the passage of time and the inevitability of change alongside gentle demonstrations of self-preservation. The title, too, intimates the sometimes messy, sometimes beautiful mapping of human experience onto natural rhythms. One might cite the title more fully within the text from which it belongs, one jointly conceived by the artists: “Here heaviness dissolves,” it concludes, “a big toe touches a green tomato.”

The project achieves a great degree of harmony even with the oscillations and variations that run across Azar and Shay’s practices. This occurs both through the range of media—which includes digital and darkroom photography, sculpture, and ceramics—as well as conceptually: the artists invoke architecture, plants, the body, and gesture to measure change as a constant force. Finding commonalities across their two practices while celebrating deviations, Azar and Shay envision the exhibition like two parallel waves that crash into and through one another.

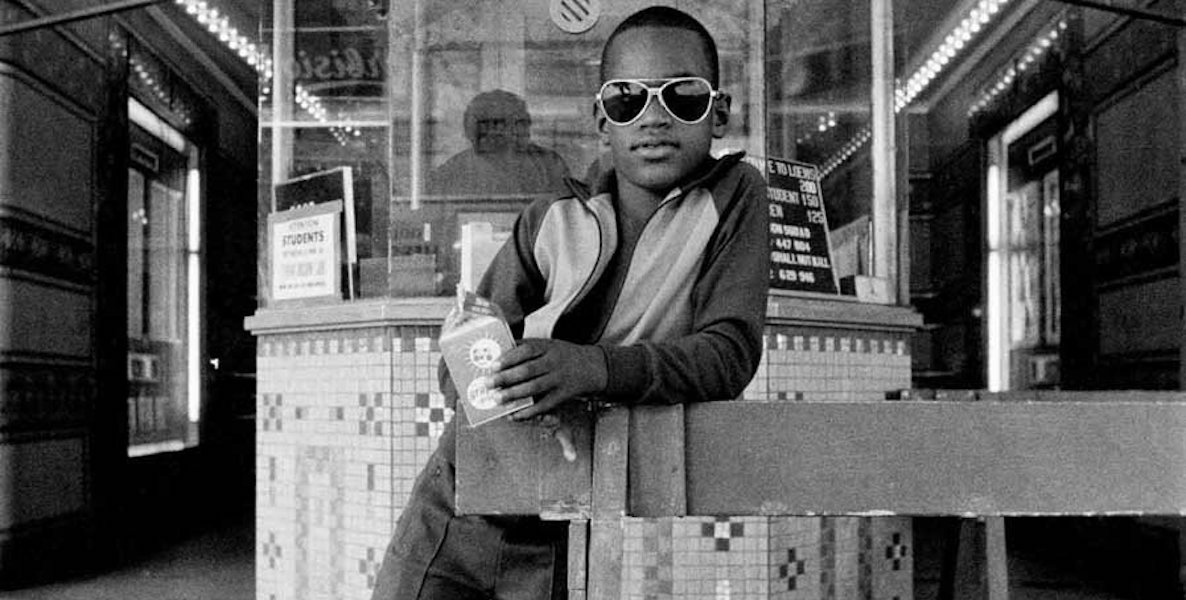

Azar’s black-and-white self-portraits limn the overarching theme of staid motion, freezing the artist in moments of varied confluence between flora and the understood human form. It is unclear in which direction one overtakes the other—much like a transitional still from the holographic covers of the 1990s science-fantasy series Animorphs. Alternatively, Azar portrays glimmers of a future in which the boundaries between nature and the body have increasingly withered away. In their place, the artist accentuates the modes of care and emotional resolve that materialize in times of vulnerable uncertainty.

Roxana Azar, Untitled (Plant), 2017 and Untitled, 2017, Archival inkjet prints

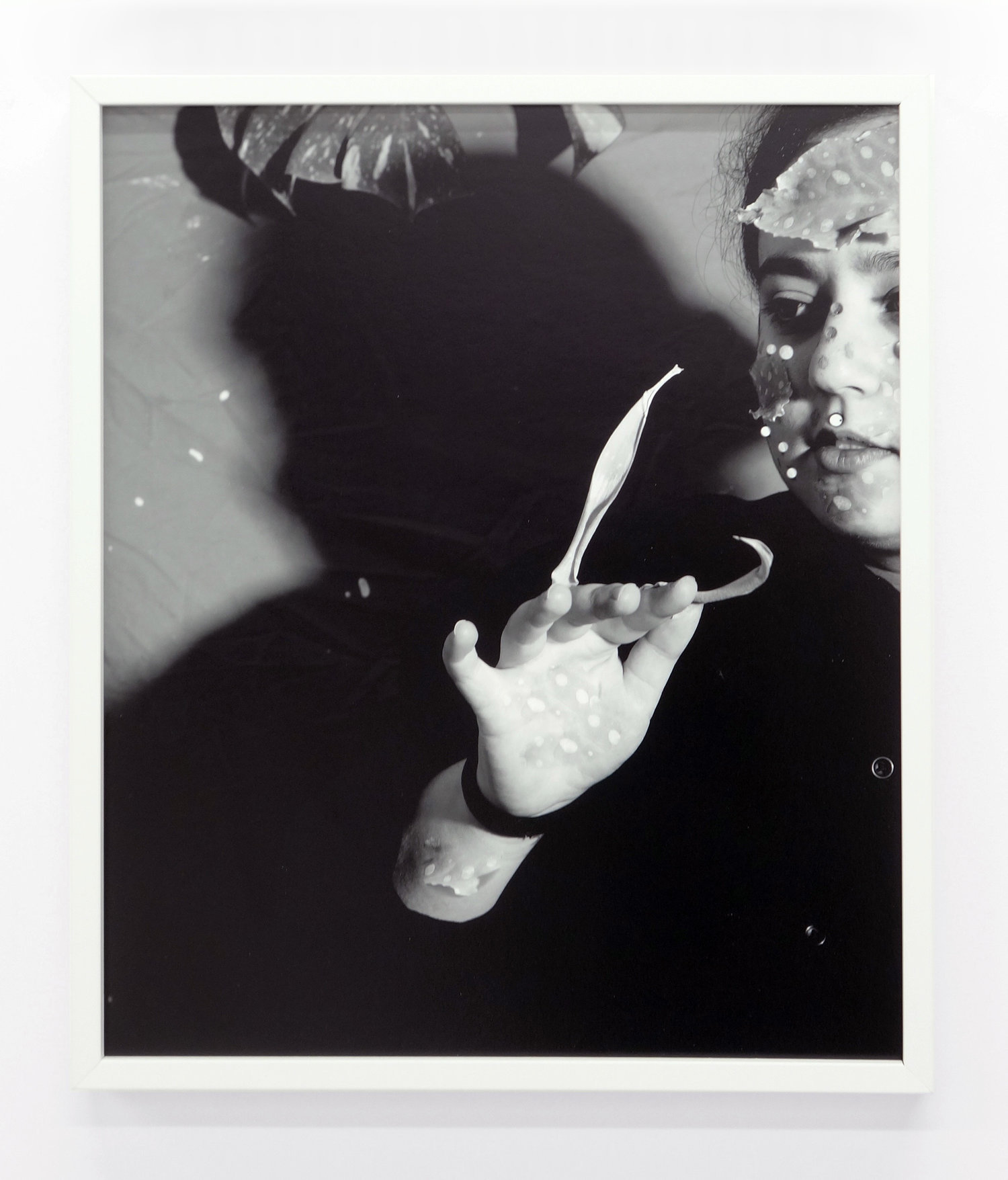

Take Untitled (Plant), where rows of gradient flower pedals enshroud Azar’s face; only their eyebrows, eyes, nostrils, and lips remain. Their expression is resigned. Presented in three-quarter profile, the representation is quite regular. However, close looking reveals how the petals are in fact not fixed to Azar’s face but instead applied and overlain digitally, acting as a layer of flesh itself. The image illustrates a resilient ambivalence, one that teeters on acceptance and surrender, while invoking both the permeability of skin and its strength as replenishable matter.

In the adjacent Untitled, Azar reveals a certain fascination with the confluence of natural and human forms. Here, petals stem from the artist’s fingers while leaves and dew cling to their face. The artist’s hand, set against a rich black background, hovers like an instrument of hypnosis. With their gaze fixed yet attentive, Azar conveys the kind of mysticism that one might expect from first realizing this hybrid overlap. By embracing wonder in this latter example and, in the former, an awareness of the inevitable, Azar gives rise to the different stages of persistence and the emotions that enable one to weather change.

Azar’s additional works in the show circumvent anthropomorphic imagery to capture a more formal and emotional dynamic. In one photograph, the artist is depicted as just the upper half of a face, which rests at the foreground atop a field of small flowers; in another, polygonal leaves sprout from the seed-like membrane of a foreign mass. Operating here as a nature photographer set on documenting a surrounding queer landscape, Azar visually replicates how one figures and navigates a world made alien.

Ginevra Shay, Magenta Sink in Foreground (Franklin Delphey Hotel), 2018. Chromogenic print (color darkroom from negative).

Ginevra Shay, Magenta Sink in Foreground (Franklin Delphey Hotel), 2018. Chromogenic print (color darkroom from negative).

Shay too fills the exhibition with a series of photographs that allegorize a social and, in this case, architectural underbelly, yet plays specifically with experimental darkroom practices as a means of metaphorizing ruination. The triptych Magenta Sink in Foreground (Franklin Delphey Hotel), for instance, shows the remains of the historic Baltimore building following a 2014 fire and years of accumulated neglect. In each scene, differences in the exposure times of white, magenta, yellow, and cyan light pull different motifs—e.g. a doorway of detritus, a chain link fence—to the fore as the series progresses; Shay even inverts one underlit panel of the trio horizontally. Each of these slight modifications contributes to an illusory sensation of decay. In so doing, architecture becomes a symbol of power and permanence while its documentation in this manner simultaneously preserves memory, stresses collapse, and subverts the linearity of time.

Ginevra Shay, Indicating, 2018. Archival pigment print from negative.

Ginevra Shay, Indicating, 2018. Archival pigment print from negative.

Alongside her analog photographs (Indicating is a particularly strong example, one that merits more consideration than this text can adequately host), Shay debuts three sculptures that unsettle a traditional sculptural vocabulary. In Hand Dropping Gingko Leaf (dedicated to Max Guy), Shay models a cartoonish hand and leaf on an elevated plaster slate, which is itself peppered with shards of colorful stone.

Ginevra Shay, Hand Dropping Gingko Leaf (dedicated to Max Guy), 2018. Plaster, granite, marble, wood, and paint.

Ginevra Shay, Hand Dropping Gingko Leaf (dedicated to Max Guy), 2018. Plaster, granite, marble, wood, and paint.

The image is at once narrative and symbolic—conjuring emoji and their open mode of communication—while its grandeur and display call to mind the remaining fragments of high-relief sculpture from the Parthenon’s frieze. Yet despite these comparisons, the work achieves a markedly gentle and delicate air. Its articulation of volume is undermined by the role of absence and negative space in carrying meaning. While many artists have broken through the patriarchal language and materiality of “monumentality” (Rachel Whiteread’s translucent plinths, Do Ho Suh’s empty bases, and Mona Hatoum’s bullet-strewn miniatures come immediately to mind), Hand Dropping Gingko Leaf, unlike its counterparts, retains the notion of commemoration while imbuing a spirit of sincerity and play—in other words, the monolith can evoke admiration without insistence through dominating formal tropes.

Ginevra Shay, Tomato Plant (dedicated to Roxana Azar), 2018. Copper pipe.

Ginevra Shay, Tomato Plant (dedicated to Roxana Azar), 2018. Copper pipe.

A second sculpture—a serpentine stretch of copper—balances upright in a corner of the gallery. Shay has bent and curved the stretch of metallic pipe into a psychosomatic scribble in space. The image is formed without the use of curved joints or fixtures; its soft winding suggests ostensible malleability and signals the delicate material handling behind its construction. The title, Tomato Plant (dedicated to Roxana Azar), adds a layer of associative import: large loops form the outline of ripening tomatoes while its curving arabesques prop up the work like vines beneath the ground. Like Hand Dropping Gingko Leaf, embedded in Tomato Plant is a tribute, perhaps to a shared moment or mindset, and explicitly to a friend—in this case Azar, with whom this entire project was conceived. Read in this way, Shay’s sculptural episodes, seen too in the preceding example, pay homage to her place within an artistic community and demonstrate a generosity of spirit not often associated with large-scale objects in space.

Tenderness comes into play once more with a final collaboration by the artists: a window display of ceramics—some by Azar, others by Shay—that contain a wild array of potted plants constituting a so-called tableau vivant. Illuminated by a hypnotic combination of red, green, and blue bulbs, the leaves, succulents, flowers, and branches glow in an unnatural wash of hues. And yet the artists’ planters—which range from pinch pots to speckled vessels and several variations in between—show their own handiwork through tactile fingerprints, slouching forms, and uneven edges.

It is as if these containers are virtuous caretakers to the unknowable lives of the plants they embrace. And so this street-facing display, together with the gallery of work behind it, airs the sensation of witnessing a world in constant flux and finding peace when a turn of events seems to press against the limits of experience.

A Big Toe Touches A Green Tomato is on view at Resort (235 Park Avenue) through March 11, 2018.

All photos courtesy of Resort.

Joseph Shaikewitz is a New York-based writer and curator from St. Louis, MO. He is an MA candidate in the Art History program at Hunter College.