Head Back & High at the BMA Offers Opportunities–Both Realized and Missed by Kerr Houston

At the left of the photograph, the artist – squatting, enrobed in black cloth, face obscured – raises her arm and tugs at one leg of a cluster of nylon pantyhose. The material responds: the leg tautens into a gossamer thread, and the curious assemblage, partly moored to a gallery wall and partly weighed down by sand, loosely begins to resemble a human in form. We sense legs; the slack central forms evoke a torso. And now the artist’s potent gesture feels almost divine, imbued with creative possibility and generative force: a descendant, in spirit, of Michelangelo’s animating Sistine God.

The intriguing career of Senga Nengudi (b. Sue Irons, in 1943) forms the subject of Head Back & High, a modest but eye-opening show at the Baltimore Museum of Art (through May 27). Organized in collaboration with Art + Practice, a Los Angeles-based art and service organization, and co-curated by the BMA’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director Christopher Bedford and Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art Cecilia Wichmann, the show is built around eight photographs, three sculptural installations, and a video compilation of performance excerpts.

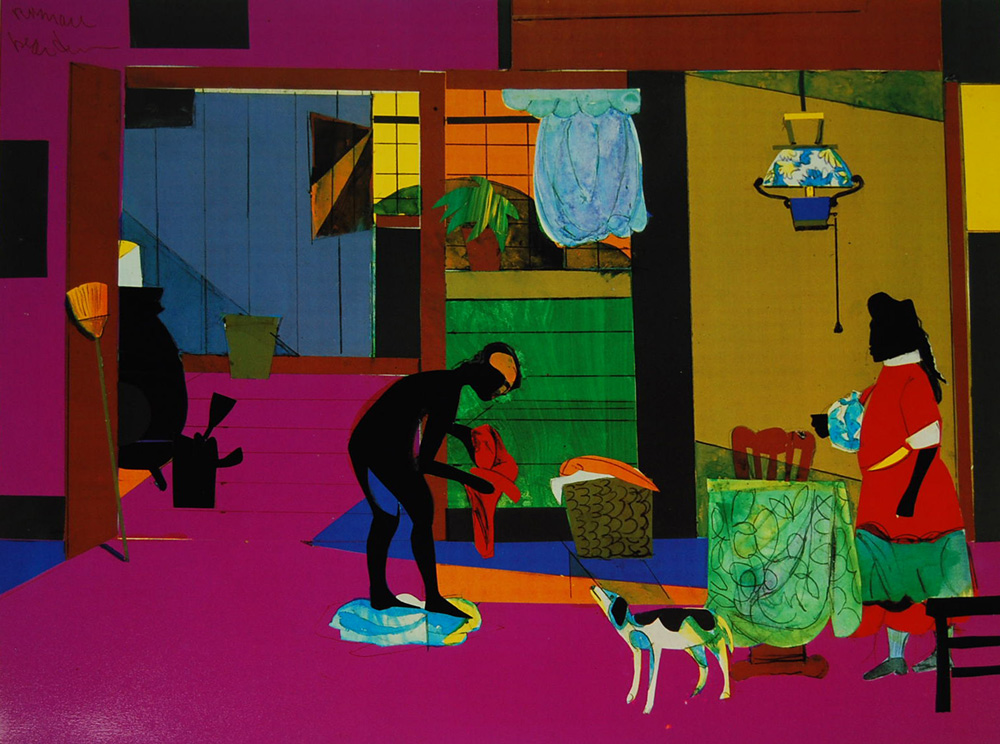

Installation view of Head Back & High. Courtesy of the BMA.

Installation view of Head Back & High. Courtesy of the BMA.

In scale and conception, then, it closely resembles a similar 2015 show of work by Nengudi at Dominique Lévy Gallery, in New York City. More generally, though, it can be seen as part of a general surge of interest in the work of Nengudi and other historically overlooked black artists active in the 1970s. Inspired in part by the remarkable scholarship of Kellie Jones, galleries and museums are now granting Nengudi a belated but deserved visibility. And, through shows at institutions such as UCLA’s Hammer Museum, MoMA, and Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum, Nengudi has effectively been re-positioned as an important member of the American post-modern avant-garde.

Nevertheless, her work remains rather difficult to classify. It does not fit easily into familiar categories, and willfully transgresses conventional disciplinary boundaries. Perhaps most obviously, it differs from the overtly political and Afro-centric art that many black artists were producing in the 1970s. Indeed, as her friend and occasional collaborator David Hammons later recalled,

No one would even speak to her because we were all doing political art. She couldn’t relate. She wouldn’t even show around other Black artists, her work was so ‘outrageously’ abstract.

Nengudi’s work was evidently, from the beginning, distinct.

This perceived gulf may have been due in part to geographic factors. Based in Los Angeles, Nengudi was literally, as well as artistically, distant from the New York art world. Indeed, L.A. could feel far from everything: as Maren Hassinger, one of Nengudi’s most frequent collaborators, recently told me, “it was an art desert… a sleepy town.” But, precisely because of its relative isolation, L.A. could also prompt open experimentalism and surprising syntheses. Nengudi’s uses of used pantyhose, for example, at once recall Bruce Conner’s alarming uses of nylon, Eva Hesse’s stunning projects in latex, and work by the German artist Rebecca Horn. And perhaps it is not unfair, too, to see a faint reflection of Joseph Beuys, who had famously tugged at a bolt of felt lodged in the mouth of a coyote, in the photograph of Nengudi drawing the hose towards herself. Nengudi’s work seems aware of these precedents, while forging something entirely new.

Joseph Beuys, I Like America and America Likes Me (detail), 1974.

Joseph Beuys, I Like America and America Likes Me (detail), 1974.

Moreover, as Jones has pointed out, California faces towards Asia, and Nengudi was clearly influenced by Japanese artistic traditions. Indeed, in 1966-7 she studied in Tokyo, and became deeply interested in the playfully iconoclastic work of the Gutai Art Association. Notably, one of Nengudi’s earliest pieces, in which she filled vinyl pouches with colored water and placed them on pedestals, drew on a similar series of works by Sadasa Montonaga group. Even more broadly, though, Nengudi seems to have been attracted to the Gutai group’s enthusiastic interest in the active body. Gutai is often translated as embodiment, and artists connected to the group frequently involved their bodies in radical ways, crashing through sheets of paper or wrestling with hundreds of pounds of mud.

Such a buoyant embrace of the physical was almost bound to appeal to Nengudi, who had minored in dance as an undergraduate. Indeed, she had initially considered majoring in the subject – but, as she later put it,

I never had a ‘dance body’ or anything like that… I personally had a hang-up about that. I continued to dance but never really did it full force because of that. And basically, even with dance, I preferred the creative side of it, choreography or developing concepts for movement.

Dance’s loss, you might say; art’s gain. For Nengudi soon began to develop an intriguing series of projects that explored the body in various states of motion, suspension, and arrest.

Many of these projects were performance-based, and the video compilation in the current show offers a sense of their tone. In a 1982 performance piece entitled Flying, for instance, Nengudi, Hassinger, Frank Parker and Ulysses Jenkins circled a pair of eucalyptus trees and mimicked seagulls, even as birds in flight were projected onto their white clothes. In an earlier work, briefly excerpted in the BMA video compilation, Nengudi, Hassinger and Parker stand in close proximity to one another and issue a series of sibilant smooching sounds, which coalesce into an improbable polyrhythm. And in a more recent piece, also included in the show, Nengudi and Hassinger slowly encircle each other while assuming potent, expressive gestures. Crossing her arms in front of her chest, Nengudi evokes tuluwa lwa luumbu, a Congolese gesture signifying willful wordlessness; a moment later, she raises her arms, seeming to testify, even as she holds – and hence the title of the show – her head back and high. The body, in such works, is associated with potential, and even transcendence.

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. Reverie – Combat, 1977/2011.

Senga Nengudi, R.S.V.P. Reverie – Combat, 1977/2011.

But Nengudi also found herself increasingly intrigued, in the 1970s, by the flexibility and resilience of her own body. Giving birth to her two children, in 1974 and 1979, made her intensely aware, as Begum Yasar has pointed out, of the dramatic physical transformations that accompany pregnancy – and of the remarkable elasticity of the female form. In turning to pantyhose, Nengudi embraced a material that was associated with the female body, and she promptly began to stretch it to its limits, filling it, pressuring it, and then watching it snap back into place.

Or almost snap back. For the nylon hose was already used, and always carried a hint of the body that had once inhabited it. The empty legs (and the uninflated inner tubes that also began to appear in her work) were vessels, once filled, then discarded, and now recuperating. In works such as R.S.V.P. Reverie – Combat, Nengudi explores the innate desire of materials to hold their form – and their equally inevitable tendency to slacken, over time. These are abstract works, certainly. But they are also ruminations on tension and on time: études arranged around the idea of embodiedness.

Senga Nengudi (with Maren Hassinger), Performance Piece (detail), 1978.

Senga Nengudi (with Maren Hassinger), Performance Piece (detail), 1978.

Importantly, though, these sculptures were not meant to be mere objects. Rather, they were conceived of as interactive: a fact evident in a group of three photographs in which Hassinger inserts herself into a network of hose, and then tests the resulting field of physical possibility. In one sense, Hassinger seems bound, her motion constricted and delimited. At the same time, though, she is also free to explore the contours of this system – and did exactly that, as Nengudi, just outside the frame, offered verbal directives and encouragement, and stepped in to lend a hand when necessary.

And so we begin to sense, after all, a latent political aspect in Nengudi’s work. Certainly it can be called feminist, both in its materials and its iconography, and (as Mel Tapley once argued) in its metaphorical allusion to the various forces that besiege the female body. It could also be called, I suppose, intersectional; after all, Nengudi once explained her stretched nylons by referring to the physical labor done by black wet-nurses, “their breasts rested on their knees, their energies drained.” Ultimately, though, the tone of her work is not plaintive, or tragic. Rather, it is strikingly affirmative, and rooted in the sheer pleasure of creative social interaction; as John Bowles once noted, friendship plays an important role in Nengudi’s collaborative work. This is an oeuvre based on collective trust, rather than outrage.

Installation view of Head Back & High. Courtesy of the BMA.

Installation view of Head Back & High. Courtesy of the BMA.

That point is generally evident in the BMA’s show, which does a fair job, in a small space, of conveying the diversity of Nengudi’s work, and the importance of collaboration to her practice. And yet, there are several ways in which this exhibition falters, or fails to fully deliver.

For one thing, the accompanying wall texts occasionally employ a cryptic and unhelpful shorthand. At one point, for instance, we are curtly told that Nengudi can be understood in relation to masquerade and kabuki. That’s not an unfair point – but the curators leave it completely undeveloped, apparently assuming that viewers will simply know that kabuki is a form of musical theater that often employs offstage performers, or that the relevance of masquerade lies largely in its synthesis of art and ritual. Faith in one’s audience is one thing – but even a brief gloss would be helpful. One senses, here, a desire for pressing economy or conciseness that verges on the self-defeating. (Note: The museum has reported that they have since changed the wall text with language less prone to imply that one would be invited to touch the work on view “to consider her work from their own personal perspectives.”)

Also confusing are the various allusions to interactivity. Nengudi valued direct involvement: she admired Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, and her work with Hassinger regularly depended upon a physical interaction with sculptural works. The BMA openly acknowledges this; one wall text states that Nengudi “encourages viewers to respond to her work as tactile, personal encounters,” while a second observes that the title of a piece on display – R.S.V.P. Reverie-O – “encourages viewers to engage personally with the works.” It’s striking, then, to realize that none of the objects on display can in fact be touched. In an era when curators have devised a range of creative ways of facilitating meaningful and sustainable interactions with seminal interactive works of art from the 1960s (Lygia Clark’s bichos, say, or Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room), the aloof and merely visual presentation of Nengudi’s work feels tonally inconsistent.

Senga Nengudi (with Maren Hassinger), Performance Piece (detail), 1978.

Senga Nengudi (with Maren Hassinger), Performance Piece (detail), 1978.

Perhaps most curious, though, is the treatment of Hassinger in this show. Given the depth of her relationship with Nengudi, it’s satisfying to see Hassinger pictured in several of the works on display, and mentioned briefly by name. But nowhere, oddly, is there a reference to the fact that Hassinger has spent the last two decades working in Baltimore. Simply put, this is a missed opportunity, as the BMA seems to be ignoring a natural connection to the local artistic landscape.

And might that inattention to the local landscape be understandably due to the fact that the show is a collaboration with the L.A.-based Art + Practice? It might, but such a concession only raises other questions. When we realize that the recent Spiral Play: Loving in the ’80s was also a collaboration with A + P, and that A + P was co-founded by Mark Bradford, who will soon have a major show at the BMA, and that bags manufactured by an Italian social cooperative sponsored by Bradford occupy a prominent sales rack in the museum lobby – well, it’s hard to avoid wondering what, exactly, all of this has to do with Baltimore. Certainly, the L.A. connection is understandable, given that Bedford once worked at LACMA, as an assistant curator. But there’s a difference between understandable and inevitable, and it will be interesting to see, in the coming months, if the museum can more fully articulate the local relevance of this stream of West Coast products.

None of this is to say, of course, that the BMA must restrict itself to merely regional subject matters, or themes. It needn’t and it shouldn’t, and it’s worth saying clearly that the chance to study Nengudi’s work on Art Museum Drive is rewarding. Still, the ways in which her work is presented can matter – if only partly. When we last spoke, Hassinger reminded me that “the seriousness of our practice is evidenced by all of the years that we spent on it without recognition.” That’s a compelling point, and one worth keeping in mind as the art world belatedly begins to organize and interpret Nengudi’s practice, and to give it a broader visibility.

Head Back & High : Senga Nengudi, Performance Objects (1976–2015) is on exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Art through May 27, 2018.

Note: an earlier version of this review claimed that there is no reference to a major upcoming show of Hassinger’s work at the BMA; in fact, the title wall does allude to the upcoming solo exhibition. Also, some of the wall texts in the show (e.g., “to respond to her work as tactile, personal encounters”) have been changed since this review was written, and now involve language less prone to imply that one would be invited to touch the work on view (e.g., “to consider her work from their own personal perspectives.”)