Edvard Munch: Color in Context at the National Gallery by Brendan L. Smith

If he’s watching from beyond the grave, Edvard Munch is probably annoyed that he’s remembered mainly for The Scream. The prolific artist created more than 1,000 paintings and 4,400 drawings that display a prodigious wealth of talent and brooding expressionist style.

The Scream also is losing its existential angst under the onslaught of popular culture, becoming an endless meme generator and flowing stream of capitalist products. In the National Gallery of Art’s gift shop, you can take home an inflatable Scream doll for only $16.95! Those kind of bargains make you want to clutch your cheeks and scream for joy rather than anguish.

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch

The Kiss in the Field, 1943

woodcut printed in red-brown with watercolor on wove paper

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen

Fortunately, the National Gallery also is interested in Munch’s work beyond The Scream. In an intimate exhibition filling two small galleries, 21 prints are featured in Edvard Munch: Color in Context. The exhibition examines the relationship between Munch’s work and the meanings ascribed to different colors by spiritualist principles, which developed in the late 19th century in reaction to rapid-fire scientific advances that posed unsettling questions that branched into metaphysical realms. If recently discovered X-rays could see through a body, then where did the spirit reside? If science trumped religion, then what happened to the soul and departed ancestors beyond that dark curtain separating the living from the dead?

Munch experimented with cameras and double exposures in self-portraits in his studio, a technique also used by hoaxsters to create “spirit” photos. In England, two girls used illustrated paper cut-outs to create photos of “fairies” which they claimed were real visitors from another realm. The photos captivated a growing audience of spiritualists, including Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes series. Doyle used less deductive reasoning than his famous detective while enthusiastically promoting the photos as authentic in a widely read article in The Strand magazine in 1920.

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch

Girl’s Head Against the Shore, 1899

color woodcut, Epstein Family Collection

At the National Gallery, visitors can examine a list displaying assorted colors and their associated meanings compiled from a 1901 spiritualist book called Thought Forms, a mystical notion that thoughts create their own colorful auras. Bluish-grey symbolized “religious feeling tinged with fear” while dark orange represented a “low type of intellect,” but the color associations are simplistic and impossibly specific. Five slightly different shades of red are supposed to convey very different emotional states, including avarice, anger, sensuality, pride and pure affection.

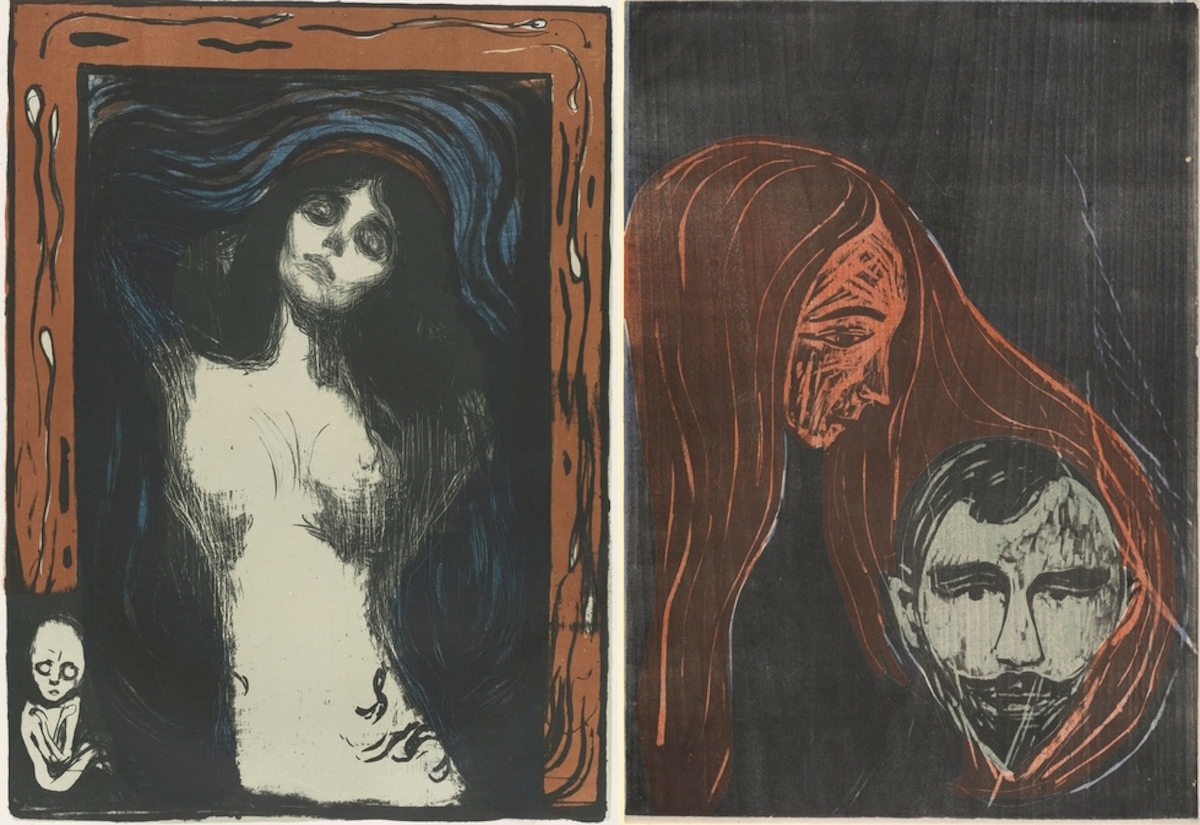

One of the most captivating works in the exhibition is Madonna, a color lithograph printed in 1913-14 and a subject that Munch revisited in several paintings and prints. A sensuous nude woman appears with her eyes closed while her upraised arms disappear behind her flowing black hair into dark swirling depths. She is framed by a maroon rectangle with sperm-like images tracing around her and a small forlorn figure resembling a deformed fetus. The work contrasts the erotic nature of lovemaking with the traditional role of women as mothers who create life through love or submission.

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch

Man’s Head in Woman’s Hair (Mannerkopf in Frauenharr), 1896

color woodcut

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection

Many of the prints are dark and brooding, evoking unsettling psychological states and unknown circumstances. In Melancholy, a woman concealed beneath a deep red dress holds her head in her hands as her jet-black hair merges into the darkened shore around her, making her seem both monumental and mysterious. Is she grieving for a lost lover or for herself? In Melancholy III, a sorrowful man rests his head on his hand on another black expanse of beach where the only respite from the gloom is a small white house in the distance, but the man seems disconnected from any of the domestic comforts of home.

While they should have been paired together rather than separated by a doorway, a color lithograph and a color woodcut both titled Anxiety offer a fascinating window into an artist’s development of one scene. In the lithograph, a group of finely dressed men in top hats and women wearing bonnets stand before rolling hills and boats floating in a harbor beneath a maroon sky. They stare directly at the viewer with pursed lips and faces taut with worry, and they seem to be waiting for an answer to an unknown question. The viewer becomes part of the scene, an accomplice in a story that is still unfolding. The color woodcut is a much rougher treatment of a similar scene, in part because of the limitations of the medium. An array of disembodied faces seem to float as their bodies are subsumed by a blackened landscape, creating a sense of foreboding without the anticipation or narrative.

While the exhibition is thoughtfully arranged, National Gallery curator Jonathan Bober uses a heavy hand in pushing the spiritualist color theme to define Munch’s palette. Munch claimed he could see auras of energy emitting from certain colors, but he never defined himself as a spiritualist. Munch was already in his late 30s when Thought Forms was published. The exhibition’s wall text states that, “Munch claimed to select his colors at random,” which needlessly casts a cloud of doubt over an artist’s statements about his own work. No one can definitively say why Munch chose certain colors other than Munch himself. He may have been fascinated by spiritualist notions like many other artists of his day, but that doesn’t mean he surrendered control over his own work to a table of colors printed in a book.

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch

Madonna, 1895, printed 1913/1914

color lithograph

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Epstein Family Collection

Brendan L. Smith is a freelance journalist and mixed-media artist in Washington, D.C.

Edvard Munch: Color in Context will be on view through Jan. 28, 2018.