Black Magic: AfroPasts/AfroFutures by Angela N. Carroll

“Maybe the present becomes very beautiful if we consider it as something already having happened. We grow closer to others by talking about the past. Just the idea of something being over, yet held onto, is a kind of love.” – excerpt from #sky #nofilter: 2016-2017, Meditations on a year when I sometimes thought I was dying by Chlöe Bass

Black Magic:AfroPasts/AfroFutures mines the Afro-diasporic visions, dreams and psychedelic premonitions of eight visual artists: Pierre Bennu, Jamea Richmond-Edwards, Ivan Forde, Adama Delphine Fawundu, Adrienne Gaither, Charles Jean-Pierre, Tariku Shiferaw, Danny Simmons, and also includes a literary contribution from Chlöe Bass. The collection at Honfleur Gallery in Washington DC assembled by Anthropologist/Curator Niama Safia Sandy is situated in distant, contemporary and future worlds that channel Afrofuturist and magical realist theory and literature. It harkens back to the exhibit of the same name Sandy curated in Brooklyn in 2016, but features different artists from DC and Baltimore instead.

Sandy notes in the curatorial statement that she considers magical realism and Afrofuturism to be “nodal points on a larger continuum of black creative expression integral not just to artistic expression but central to the very act of moving through the world as a black person in modern society.”

The exhibition includes works that incorporates abstraction, portraiture, and assemblage which all buck against strict categorization. In this exhibit, abstract hip hop homages are installed adjacent to dystopian fetishes. A stylized soul and real soil from South Africa are enshrined within an interactive shutter sculpture. Family portraits are obstructed by geometric shapes and deconstructed playing cards. Black male godheads confront colonial geographies. Astral black female nudes float in etheric non-places. Time traveling silhouettes imprint themselves on the ephemera of American history.

Visitors will first encounter Tariku’s “Black Diamonds & Pearls (Blackalicious)” a work that exalts hip hop culture—every painting in the larger series is named after a classic hip hop album. The song “Black Diamonds & Pearls” by Blackalicious is a rallying affirmation, a profoundly inspirational and motivating anthem. The chorus proclaims:

Keep on, keep going, march on, move on, keep blowin’ it up

Keep ON, keep going, march on, move on,

Stay strong, keep going, keep blowin’ it up

There are similarities in the way hip hop culture inspires Tariku’s work and jazz resoundingly influenced the action paintings of Jackson Pollock. Both paint the gestural reaction of the artists body as it responds to the music as a visual mark. “Diamonds & Pearls” is a minimal abstract reimagining of the song; the music is visualized with six black rectangular bars and color. Broad strokes of bright blue paint roughly render diamond-esque shapes across the center of the plastic canvas. The black bars overlay the blue. I appreciated the wit of Tariku’s homage; the stacked black bars, “bars on bars,” are a colloquial inference to lyrical mastery.

Danny Simmons’ “Hocus Pocus” and “Erasure” present another example of dynamic mixed media abstraction. In “Hocus Pocus,” simply rendered circles, dots, short dashed lines clutter in dense layers on the canvas. Jagged scraps of gold, crimson, and blue koi fish brocade tapestries color an otherwise black and white palette. A large splatter of white paint stains the abstraction and drips down the canvas. In “Erasure,” Simmons echoes the reduced geometries of “Hocus Pocus” but includes bright colors and sparse textural references, small dots within yellow splashes of paint, red and peach squiggles. The circles and colors grid and fracture the composition. A large splatter of white paint drips atop and underneath the odd geometries.

Both Tariku and Simmons appropriate abstract expressionism, a historically exclusionary canon, to subvert classist historiographies, and elevate hip hop culture and black creative expression, movements that are often segregated from contemporary art canons or relegated as “low art” within “high art.”

The portrait works selected for Black Magic are transformative; each expands visualizations of black identity in atypical ways that do not rely solely on realist corporeal depictions. Supernatural, meta representations dominate and invigorate the exhibition and establish the presence of black bodies in myriad iterations of space and time.

Jamea Richmond-Edward’s “Consequently Vulnerable,” a large diptych portrait of a black female nude, is installed adjacent to Tariku’s homage. Edwards is known for creating regal portraits of black women and girls. The characters are adorned in dense layers of fabric and mixed media and are situated in non-specific, often etheric, interdimensional atmospheres. The interplay between the infinite black of space, dark matter, deeply hued melanin and solitary representation of the women she portrays also recur.

“Life begins with Black women,” Edwards shared with me during the opening reception. “We are powerful but there is also a sense of vulnerability.”

“Consequently Vulnerable” is what the title suggests, a completely bare portrait, but Edwards queries perceptions about the vulnerability of black women’s sexuality. Edwards shows restraint, the flamboyant mixed media she typically incorporates is absent, very little texture, no excessive frill or fabric. The woman in the portrait is beautiful; she emerges from the inky black cosmos haloed by an auric blue. Her stance is self-assured, a lone woman, standing in the infinite black of space among the faint glitter of solar systems and stars. Her expression is fearless. The woman stands comfortably in her nakedness, and her oppositional gaze defiantly confronts all who view her.

Popular media representations of black women’s sexuality have a disturbing history; often polarizing black womens’ characterizations as either asexual mammie or hypersexual thot. Those flat, generalized depictions of black womens identities do nothing to illustrate the humanity, complexity or agency of black women. As Audre Lorde describes in Zami, A New Spelling of My Name, the hypervisibility of “Othered” women inherently renders them, “invisible through the depersonalization of racism.” The residue of that violence and violation, the display of black female bodies solely for colonial and/or capital consumption, weight and contextualize Edward’s work. “Consequently Vulnerable” considers these histories and audaciously rails against them, showing that black nude portraiture can be edifying, and divine.

Ivan Forde’s silk screen and cotton works, “Satan on the Bare Outside of Our World” and “The Fruit,” exist in similarly nondescript landscapes. In “Satan,” Forde depicts a large portrait of a black man as he turns his head from profile to front-facing. The movement is presented as a swift action, one head that contorts so quickly it appears as three. One hand holds a compass, the other arcs above the mans brow in a state of curious survey over a black and white dot matrix environment. Though the man bares the tools of an explorer, one wonders if he will be perceived as Satan, a demonic savage presence outside of Europe, or if he is the one looking for a Satanic presence outside of the African Diaspora.

The dot matrix in Forde’s work recalls the inception of geographic delineation, map making and the fortification of colonial territories around the world. Forde’s portrait made me immediately think about the triple consciousness Frantz Fanon experienced while traveling on a train in Europe. A white child pointed, screamed, cowered in his presence. The boy was triggered by Fanon’s black masculinity, a feature he considered monstrous and fearful. We presume a homogenous and universal imagining of who or what an explorer is and the characteristics of a demon. “Satan” speculates some of the histories that precede and inform those associations, and queries viewers raced and gendered presumptions.

Adrienne Gaither presents a series of digitally altered family portraits. Black and white photographs of her paternal and matrilineal family dating back to the Reconstruction, are superimposed with blocks of colorful geometry and deconstructed playing cards.

In “JENƏˈRĀSH(Ə)N/ reconstruction,” one of the ten displayed mixed media collages, a large black and white headshot of a woman is obstructed by abstraction; black and white bars, surround her head, a white rectangle and a black inverted triangle cover her eyes. A faint overlay of the playing cards repeats across the portrait. The card games Spades and Bid whist are staple familial traditions for many black American families. Gaither’s series enunciates history and memory as virtual spaces defined and remembered by photographs and intergenerational pastimes.

Adama Delphine Fawundu’s floor to ceiling collaged screen print installation, “In the Face of History” series is a masterful revisionist imagining of the persistence of black presence throughout history. Fawundu imprints black or red silhouettes of the back of her own head, with identifiably ethnic hairstyles, onto the print ephemera of significant events in American and European history; Japanese internment bulletins, lynching newspaper headlines, minstrel show advertisements and others.

The woman is a specter and spectator at these events, many of which detail violence against black bodies, or promote racist depictions of black people. The woman is simultaneously present and somehow out of place. Her silhouette often obscures much of the ephemera in which it is imprinted, which brings up questions about the undocumented role of black people, and black women specifically in history.

“At what point do we confront these histories?” Fawundu asks, when I pose questions about the installations intentions. “Once you connect the history,” she continues, “you see that its old, but still speaks to the contemporary moment.”

Pierre Bennu contributes three assemblage fetishes from the Future Artifacts project, “The Listener (ceremonial use: Inspiration),” “The Eater of Fear (ceremonial use: Protection),” and “The Master of the Cipher aka the MC (ceremonial use: Clarity).” Each assemblage utilizes e-waste and found objects to form masks, presumably imbued, as the titles suggest, with supernatural properties that can be invoked through ceremony. I was most intrigued by the materials Bennu employed to create his fetish objects, some of which include bark, projector bulbs, lotus seeds, copper, thread, cowrie shells, radio tube, horns. The items are sourced from ancient and contemporary cherished tools and technologies.

I think it is worth mentioning that the history of fetishes, what are now termed “African art objects” stem from colonial discourses, and archival practices. Fetish and primitive are synonymous, erroneous and a deeply flawed contextualization for African religious and cultural practices considered worthless when compared with commodifiable resources like gold, rubber, cobalt, diamonds, tungsten or other precious materials sourced from Africa. Western archival practices persist in delegitimizing fetish objects’ regional practices and customs of those countries as inferior to colonial traditions.

Bennu considers his fetishes “altar pieces to rituals that have yet to be developed; imagined artifacts from a hypothetical Afrofuturist Dystopia.” His appropriation of fetishes asserts them as timeless capsules, clues to the material culture contemporary society depends on and easily discard, the resources we deify and exploit.

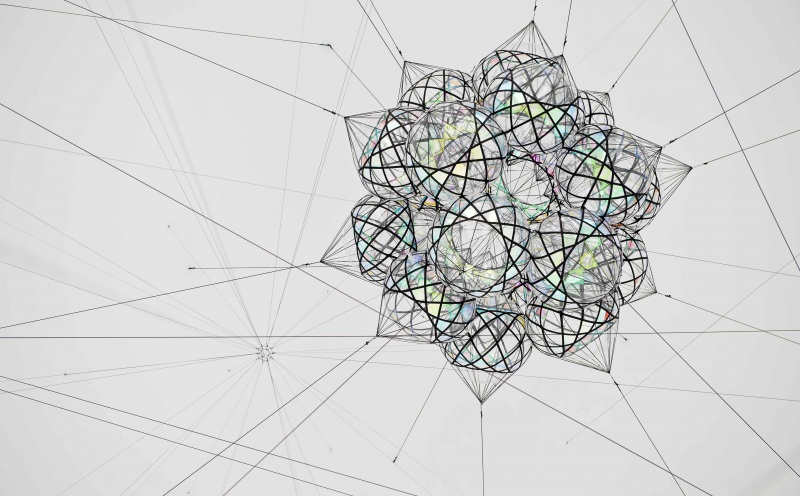

Charles Jean-Pierre’s, “Black (W)holes,” an interactive mixed media sculpture, also uses found objects. In his installation, the objects are combined to elude to real and spirited intersections between African Americans in Washington DC and South Africans. Like Thailand spirit houses, “Black (W)holes” is a structure designed to hold a soul, represented by a blue glowing lamp. The soul floats above soil from South Africa and a strip of turf that rests at the foundation of the structure. Made from old shutters sourced from a warehouse in Washington DC, viewers are encouraged to open and close the wooden blinds to reveal the sculptures interior. South African Ndebele beads hang on the interior walls of the structure. A collection of rusted cans hang at the structures center. Jean- Pierre considers the sculpture “like a body” and the cans to function as “a mode of communication from body to soul”.

Interacting with “Black (W)holes” brought up many questions for me. I wondered what was being communicated? What was lost in translation? Black Americans, descendants of Africans, have long struggled with questions of how to connect with African cultures, traditions and ways of being in earnest and non-exploitative ways. Recent debates about the appropriation of African attire and adornment by black Americans, as gloriously and imaginatively displayed in Afropunk and other summer festivals, troubles the intention of surface attempts to embrace those cultural connections.

African. American. Black. Jean-Pierre’s installation seems to be grappling with the fragments of identity. The container is a shell, filled with hopeful projections about the persistence of diasporic connections. Diasporic futures are presented as unstable and fragile, unsettling and unsettled. In South Africa white people are called “howly’s,” one without breath, one with no spirit. Black people can be howly’s too. I read “Black (W)holes” as a reclamation of the spirit, a call that one’s soul, one’s origins, are always present, and actively communicating through the materials that surround us.

Black Magic contemplates Africa and America as conceptual and historic sites of genetic and familial origin and attempts to engage those intersections through imaginative means. Black Magic does not provide all the answers, but it does offer relevant perspectives about the role of futurist imaginings in engaging real and desired Afrodiasporic connections.

#sky #nofilter: 2016-2017, Meditations on a year when I sometimes thought I was dying by Chlöe Bass

#sky #nofilter: 2016-2017, Meditations on a year when I sometimes thought I was dying by Chlöe Bass

Black Magic:AfroPasts/AfroFutures is on view at Honfleur Gallery DC until October 7, 2017. Check out the Artist Talk on Saturday, September 16, 2017 5-7 p.m.

Photos by Corey Thompson