It’s entirely possible that you may not have noticed, given the headline-grabbing antics of a prominent pussy-grabber down the road, but 2017 has already been a rather remarkable year for the arts in Baltimore.

A quick review, in case you’ve been consumed in crafting protest signs or fighting trolls on Reddit. Over the past three months, the BMA offered visitors a chance to study dozens of works by Matisse and Diebenkorn, gave a gallery to the saucy interventions of the Guerilla Girls, and mounted rare works on paper by Julie Mehretu and William Kentridge. Local galleries staged engaging shows of paintings by seminal area painters – Grace Hartigan at C. Grimaldis Gallery, and Timothy App at Goya Contemporary – while The Contemporary facilitated an ambitious, idiosyncratic installation by Michael Jones McKean. Even the discourse surrounding the arts has been robust and affirmative, as MICA hosted a lively discussion about censorship, Sharon Louden took part in a conversation about sustaining a creative life, and City Paper ran a deft extended feature by Maura Callahan and Rebekah Kirkman on the artist tenants of the Bell Foundry.

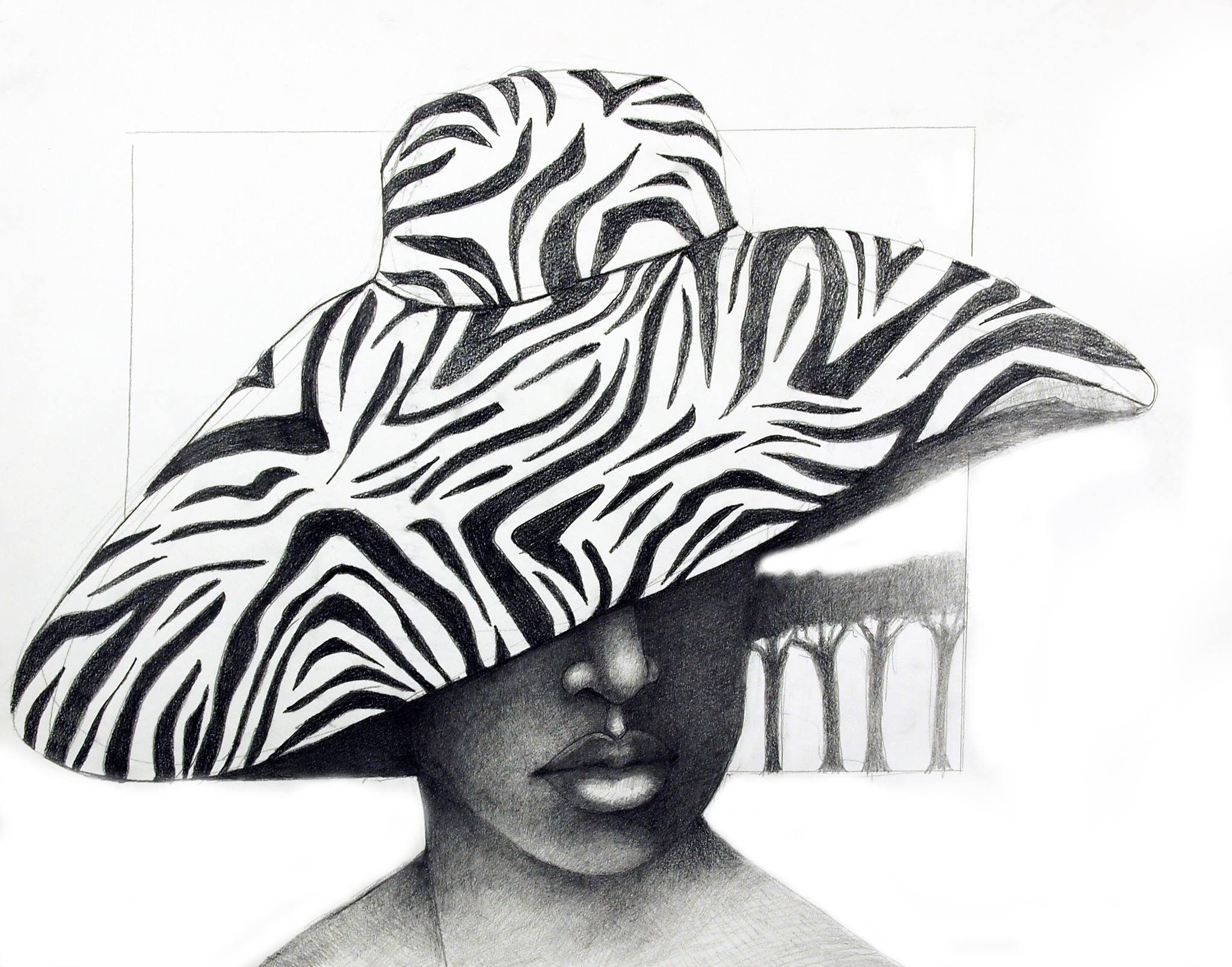

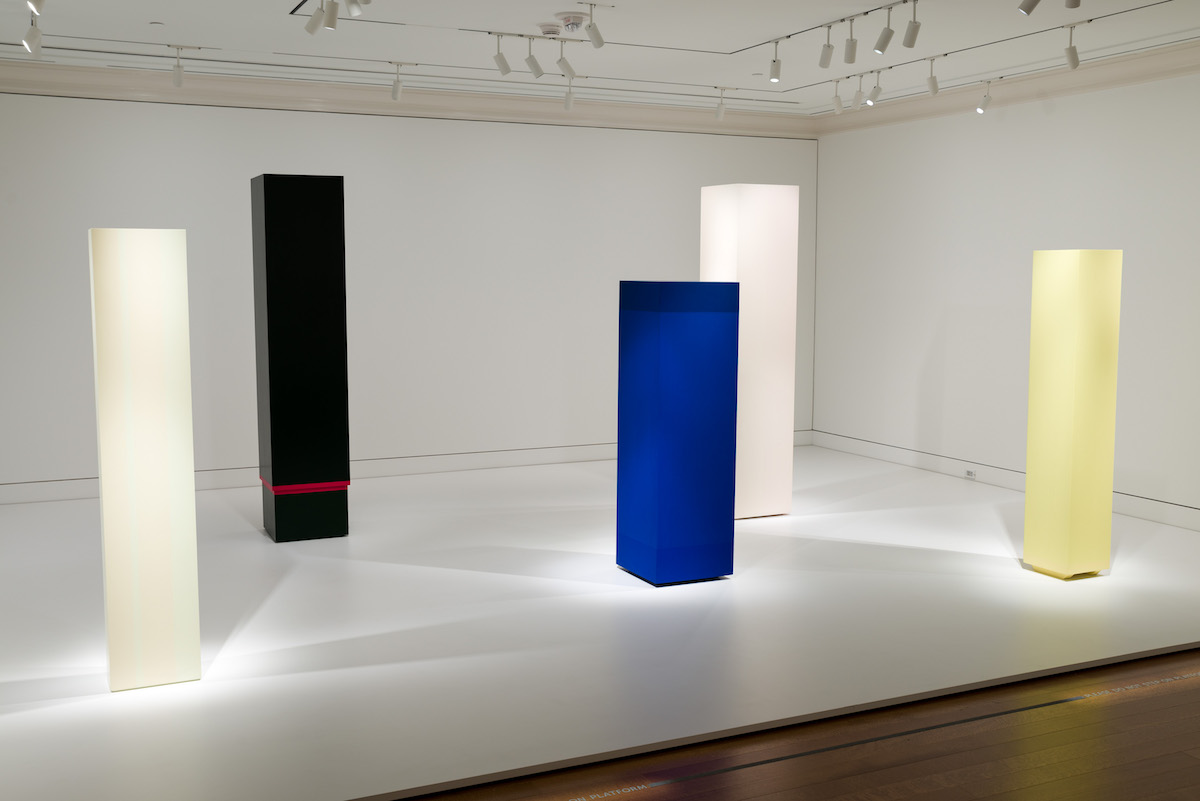

All of which is to say that you’re excused if you haven’t yet spent some time with the quiet, elegant installation of five pieces by Anne Truitt now on view on the BMA’s ground floor. When you do, though, you’ll be rewarded. Entitled Anne Truitt: Intersections, the single-room exhibition is modest in scale, but meaningfully complex in its implications. On an art historical level, it offers a welcome chance to think at length about Truitt, who first gained notice in the 1960s and whose work is generally seen as related to (but also distinct from) the larger project of Minimalism. And on an institutional level, this little show reveals a good deal about the priorities of the BMA under its new director, Chris Bedford. In sum, it does more or less exactly what a museum show should do, presenting iconic works in a way that implies their current relevance, while also framing them in provocative, productive ways.

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

So there they stand: five square columns, roughly human in scale, and richly various in hue. Dating to the 1960s, they belong to a memorable band of work produced after Truitt found herself strongly affected by the 1961 show American Abstract Expressionists and Imagists (seeing the work of Barnett Newman, she later recalled, “had set me to thinking about my life in a whole new way”). Back in her studio, Truitt abandoned her earlier experiments with wire and textured clay, and began to work with a clarity and confidence that were almost searing in their intensity.

The new works were made of wood, which Truitt then painted in layer after layer of acrylic paint, using increasingly fine sandpaper in order to create a surface that was so smooth that it looks almost ethereal. Rejecting the overt gestural quality and the densely worked surfaces of the abstract expressionists, Truitt’s columns are closer in spirit to the paintings of the Washington Color School. But where Morris Louis’ ribbons of paint seem almost organic in their bright, boisterous arrays, and Kenneth Noland’s geometric forms can betray an earnest handmadeness, Truitt’s forms seem to aim at something more potent, more sublime, more absolute. “I abandoned,” Truitt later wrote, “all play with form for the austerity of the columnar structure, and let the color, which must have been gathering force within me somewhere, stream down over the columns on its own terms.”

The result is both sensuous and profound. In Whale’s Eye, for instance, the upper section is a rich San Marino azure, while the body is a pure field of Klein International Blue, a deep ultramarine. Conventionally, we would say that the column is painted, but in fact the paint almost seems to exist on its own: to float, or even to simply appear, as if released from any material support. “Painted into color,” as Truitt put it, “this wooden structure is rendered virtually immaterial. The color is thus set free into space…” And so in looking at a work like Whale’s Eye we feel something of the ravishing disorientation also generated by Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings, or by Anish Kapoor’s Mother as a Void: instead of acting as a merely incidental quality, color here dissolves and subsumes, assuming an encompassing primacy.

Detail of Anne Truitt: Intersections, with Whale’s Eye (1968) at left, Photograph by Kerr Houston

Detail of Anne Truitt: Intersections, with Whale’s Eye (1968) at left, Photograph by Kerr Houston

By 1963, Truitt was showing some of her new works – only to watch, bemused, as they were assigned overdetermined positions in a series of increasingly polemical art critical debates. Clement Greenberg offered a qualified endorsement, employing a casually sexist language (Truitt’s works, he claimed, flirted with the look of non-art) in arguing that she was a proto-Minimalist. And certainly the stark geometry of her columns and the way in which they casually blurred the lines between painting and sculpture did anticipate the work of artists such as Donald Judd – who was just then beginning to argue for the importance of Specific Objects, which were neither painting nor sculpture (and who claimed, in a review, that Truitt’s work “looks serious without being so”). And then, too, there was Michael Fried, whose celebrated 1967 essay “Art and Objecthood” emphasized the roughly human scale and hollow aspect of much Minimalist work, and condemned it for what he saw as a misguided interest in performativity and theatricality. Fried’s position was uncompromising, and his implication clear: work such as Truitt’s constituted a confused misunderstanding of the very principles of a self-critical Modernism.

Truitt was understandably ambivalent about such readings. After all, Greenberg’s approval was no small thing – even if it was muted, and even if the aging critic was increasingly seen as out of touch with recent developments. And certainly there were points of contact between her oeuvre and pieces more generally understood as Minimalist. Her pieces did sometimes suggest, in their scale and symmetry, a loosely human aspect. (As the art historian James Meyer has noted, in an adroit reading of Truitt’s work, “a bodily identification is induced, a somatic perception invoked.”) Indeed, it was this quality that had led an unsettled Fried to claim that finding oneself before a Minimalist sculpture “is not entirely unlike being distanced, or crowded, by the silent presence of another person.” In a way, Truitt’s columns demonstrate the aptness of such a reading, for they stand like mute witnesses, testifying to their presence in a manner that only affirms their thereness.

And yet Truitt clearly sensed the limits of broad categorizations, and resisted them. “I have never,” she stated in 1987, “allowed myself, in my own hearing, to be called a Minimalist. Because minimal art is characterized by nonreferentiality. And that’s not what I am characterized by.” Rather, as Kristen Hileman (now the curator of contemporary art at the BMA) showed in a satisfying 2009 essay, Truitt’s pieces were commonly rooted in her own experiences and memories. They often bore titles that evoked intensely personal associations: Odeskalki, for instance, was derived from a late-night fireside chat with a friend, who told Truitt of a Hungarian nobleman who had been hanged on a meat hook. Far from being chaste exercises in form, Truitt’s pieces are thus bound to specific lived experiences. Or, as Meyer once put it, “The memory is there; the work embodies it.”

The five columns on view, then, are not mere exercises in abstraction; they are responses to private, singular experiences. But, given that, it is tempting to read the entire group in a biographical sense. In a journal entry, Truitt once claimed that in college she had been “obsessed with the idea of myself as a citadel.” As Hileman pointed out in 2009, that provocative analogy – in which the self is construed in stout, defensive, architectural terms – seems to anticipate the resolute verticality of her sculptures. And at another point, Truitt openly compared her two parents to monoliths – adding that, when his father died, she in turn also became a monolith. Did her two younger sisters, as well? Truitt didn’t refer to them, in her writings, in such a manner. But as one stands before this assembly of five totemic forms, which at once recall bodies and menhirs, it is hard to shake the sense that we are looking at an abstracted rendering of an assembled clan: a subtle commemoration of family.

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

And yet, as far as we know Truitt never intended for these five pieces to be shown in such a combination. Rather, they were evidently conceived individually – and were acquired variously by the BMA, gradually taking their place in a substantial collection of works by Truitt (whose seminal First, from 1961, is currently also on view in the museum’s Contemporary wing). For this exhibition, Hileman explained to me, the choice of work was governed largely by formal demands: the confines of the gallery space, and the diverse, individualistic palettes that characterize her sculptures.

That’s certainly fair: the first duties of a curator are inevitably rooted in the specific works themselves. At the same time, though, it seems clear that this show of work by Truitt was developed with larger ideas in mind. In recent months, the BMA has done a great deal to recast the experience of entering visitors, and it’s worth thinking at least briefly about how this show thus plays a part in a larger museological project.

The most radical change, of course, involves the rehabilitation of the museum’s traditional, formal entrance. Placed at the top of a dramatic set of stairs, the large portal features two massive sliding bronze valves, and can feel almost forbidding in its scale and associations; as Carol Duncan once noted, such entries suggest that the art museum is a modern, secular, equivalent of a temple. Indeed, it was that intimidatingly moralizing aspect (along with a healthy push from the ADA) that led many museums to construct more modest, humane, and transparent entrances in the late 1900s.

Thirty years later, though, a resurgence of interest in institutional histories and an apparent sense that we are now consciously aware of the limitations of such traditions has prompted a general return to earlier designs. And the result, one has to admit, can be quite exhilarating. The architectural historian Vincent Scully used to claim that, in arriving at New York’s elegant Penn Station before its destruction, “you entered the city like a god.” Mount the stairs of the BMA, stroll through the large doors into the renovated Fox Court, and you can gain at least a sense of what he meant.

Installation view, Oliver Herring: Areas for Action, Photograph by Kerr Houston

Installation view, Oliver Herring: Areas for Action, Photograph by Kerr Houston

Or stick to the ground level – for there, too, the BMA has been rethinking its appearance. Until recently, the first rooms that one encountered upon entering the BMA at ground level were generic, underused spaces, hung with partial histories of the museum. Over the past year, though, they have been reconceived, and now offer a dynamic and thoughtful overture. At the moment, the first thing one encounters is a row of video monitors playing recordings of recent actions directed by the German artist Oliver Herring. Interested in fostering social interactions and opportunities for playful improvisation, Herring loosely directs groups of volunteers, who then experiment with basic, raw materials. In the videos on view, plucky participants spray one another with colored dyes, whose residues form brilliant arcs on the gallery walls; the result is generally boisterous and affirmative. But placed here, as a sort of entrée, the work acquires a larger significance, as it implies that the BMA is a museum where active participation is valued, and where contemporary art takes place.

Just beyond the first room is a more ambitious installation entitled Imagining Home. In some ways, it’s a rather conventional meditation on the theme of home, featuring a number of works from the museum’s collection that were made with a domestic use in mind, or that foreground the themes of shelter and family. The diversity of objects on display, though, quickly complicates any attempt to pigeonhole the show, and several of the pieces are surprisingly touching. Equally disarming, though, are the recorded interviews with local Baltimore residents who were allowed to live, for a time, with an object of their choice. Through this process of temporary loans – an idea occasionally practiced by other museums in recent years, as well – the works literally became a part of a home, and the line between public and private is momentarily dissolved.

Detail of Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Kerr Houston

Detail of Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Kerr Houston

It’s with those ideas in the air, then, that one finally arrives at the final introductory gallery, which now features the five pieces by Truitt. And certainly the notion of home is a relevant one here, for Truitt was born in Baltimore and raised on the Eastern Shore, before eventually settling in Washington, D.C. Indeed, critics have long suggested that her work is somehow informed by the specific features of the region. Thus, Walter Hopps once claimed that “in her most important work something of Truitt’s experience, the actual perceived qualities and physical nature of the landscape, the buildings, light and color of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, exist within the work.” It’s an airy claim, to be sure, but also an intriguing one – and it underlines the neat appropriateness of the area’s major regional art museum dedicating a show to Truitt.

Importantly, though, this isn’t the museum’s first exhibition of her work. In 1975, the BMA mounted a show of Truitt’s paintings, and in 1992 an ambitious exhibition entitled “Anne Truitt: A Life in Art” focused on her sculptural practice. Still, the current show hardly feels redundant. Rather, it’s a neat illustration of the BMA’s evolving history: of the interests and expertise of its current curatorial staff (Hileman had recently curated a show of Truitt’s work at the Hirshhorn when she arrived at the BMA in 2009), and of the institution’s sustained commitment to the artist, over several decades. In writing about Truitt, James Meyer once observed that “each sculpture is the residue of a memory or chain or memories triggered during its completion.” He was speaking, we understand, of the artist’s own memories. But now these works also evoke our own memories – of seeing Odeskalki at the Hirshhorn, for instance, or of reading John Dorsey in the Sun, on Truitt’s 1992 show. Meyer noted that “We bring to her titles our own associations, if any.” So, too, to her pieces.

Inevitably, such associations vary by individual. But the BMA is clearly aware of that fact: in fact, it’s a guiding principle of this show. In invoking intersections in the exhibition’s title, the BMA evidently wants us to think about connections between Truitt’s work and other artistic traditions represented in the collection. To this end, the gallery features lengthy wall texts by Hileman and two associate curators: Frances Klapthor loosely compares Truitt’s ethereal colors to the shimmering surfaces of Buddhist priests’ robes, and Shannen Hill considers the importance of vertical forms in traditional African art.

Such statements, admittedly, can feel a touch strained, for they necessarily simplify immense cultural and contextual distinctions. And yet the spirit is admirably game: in organizing the show in this way, the BMA is trying to foster a conversation between its curatorial departments, while openly acknowledging that our responses to works of art need not be monolithic. Does the asymmetrical positioning of the columns remind you, perhaps, of the idiosyncratic placement of the rocks in a Japanese rock garden? Carry on, the museum seems to say. Indeed, it actively validates such thoughts, as Klapthor’s text points out that Truitt spent more than three years in Japan.

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA

In sum, then, this is an elegant little show that does a number of things well. Truitt’s work is potent; it easily holds its own. But the positioning of this show in the recast sequence of spaces that greet visitors to the museum is also effective. In raising the idea of home, the BMA nudges us to consider Truitt’s work in relation to regional schools, and geographies. In stressing the theme of intersections, it urges us to see her work in relation to the museum’s collection as a whole. And in placing Truitt’s work near Herring’s, it challenges us to think about art’s recent histories.

As James Meyer once pointed out, Truitt’s work clearly anticipates, in meaningful ways, the post-1990s practices of Roni Horn and Félix González-Torres. Rather wonderfully, important works by both of those artists are on view in the BMA’s Contemporary Wing. Take a few minutes, then, to stand in front of Truitt’s columns: to bathe in their color, and to mull over their associations. And then head for González-Torres’ beaded curtain, parting it like a veil and running your hands through its droplets. The time is now. The headlines can seem dark. But the power of these artworks is only redoubled.

***********

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.

Top Image: Installation view, Anne Truitt: Intersections, Photograph by Mitro Hood; courtesy of the BMA