Talking Artists and Development with AS220 Co-Founder Bert Crenca by Bret McCabe

Le Mondo plans to open a venue at 404 N. Howard St. this year. This space, called Mondo, will occupy one of the three building the organization is currently rehabbing and renovating, and comes about four years after its cofounding creative directors—EMP Collective’s Carly Bales, Annex Theatre’s Evan Moritz, and the Psychic Readings Company’s Ric Royer—first started organizing and talking about creating an artist-founded/owned multi-use performance incubator/cultural hub in the Bromo Arts District. Mondo will be the nonprofit organization’s debut venue.

And it still needs a little help to get there. The Let’s Open Le Mondo! Crowdrise campaign it launched in December is, as of March 10, about 75 percent of the way toward its $60,000 goal, and they’re throwing a fundraising bash March 16 to help them get there. The evening features a free public talk by Bert Crenca, founder of the AS220 space in Providence, RI, that Royer cited as an inspiration slash model of artists as responsible urban developers for Le Mondo. The free public talk and cocktail hour at Current starts at 6 pm is followed by a ticketed dinner, drinks, and performances at Mondo at 7.

AS220 grew out of artists’ organizing in the early 1980s and programming beginning in the mid ’80s, a story Crenca talks about in interviews and his 2013 TEDx talk. He’s a refreshing no-BS talker and, and BmoreArt caught up with him by phone to talk about artist-driven organizing, alternative spaces, development that displaces people, and the importance of artists being able to afford to live and work in the cities that are branding themselves as arts and cultural destinations.

What follows is a bit long, but Crenca brings three-decades of navigating issues that Baltimore’s artist communities—yes, plural, as we know we’re not one big, happy, single, arts community who shares access to the same resources and opportunities—are currently wrestling with, problem solving, and fighting for a foothold in.

He mentions a few things I’m going to link to here just as background info that you can refer to when and if needed: New York’s alternative arts spaces P.S. 122, PS1, and La MaMa. Late Republican turned independent Providence Mayor Vincent A “Buddy” Cianci Jr., who in 2002 was convicted in federal for racketeering but who is often recognized for also presiding over the city’s reinvigoration. He was the American mayor who first introduced the idea of arts districts with tax breaks/incentives for artists, and Providence’s creation of such a district in 1996 was cited by The Baltimore Sun as the model for Maryland’s arts and entertainment districts, created by legislation signed by then Gov. Parris Glendening. Crenca also mentions the idea of asset based community development, ABCD, and the grassroots organizing that used it to create a community land trust in Boston’s Dudley Street neighborhood. The conversation has been edited for clarity and cohesion.

I read a few interviews with you and watched your TEDx talk about the original organizing that led to AS220, the negative review of your work that led to artists in Providence meeting up and drafting the “New Challenge” art manifesto, and the push to open up a space. Could you tell me a little bit about the climate of the city at the time? Was there other organizing going on or these big discussions taking place? Or was this the first activity of this sort to address something bigger going on at the time?

Bert Crenca: There had been a number of different kinds of artist groups that had been doing some things here and there, but it was extremely limited. The city, in 1985 when we started or 1983 when that whole process started with the manifesto, was at its lowest point. The entire downtown was pretty unoccupied and people almost forget, now, what a negative attitude people had about Providence, both people who lived there and people from the outside. At the time people referenced it as the armpit of New England and things like that. In its heyday, it was incredibly vital city with its geographic location between New York and Boston.

And then the whole thing happened that happened in most Rust Belt cities where factories, particularly the textile industry, moved south and then one industry after another left town, and [city residents] moving into the suburbs with the highways and the malls and all that. It’s a fairly typical story for a northeastern urban center, but not too many can claim it to be as funky for as long as it was in the sense that we suffered a couple of the depressions or recessions if you will, or as my father used to say, “It’s a recession if you have a job, it’s a depression if you don’t have a job.” But for a couple of the recessions that happened that were in this region, we were first in and last out all the time.

Also, the ’60s and ’70s movements of urban renewal did not affect us. There’s an upside in that, as a lot of the architectural integrity of the city and a lot of what was historically charming about the city was not destroyed or demolished with some of the new wave ideas about buildings and architecture and urban stuff like they did in Hartford, [Connecticut], for example, where they knocked down a lot of buildings to put up high rises—and not too long after, half those high rises were empty.

So as far as the state of psychology of the community and the people in it, particularly people in the arts community, I believe, it was pretty depressed. And, for the most part, if you were an artist that was career minded, you ought to go to Boston or New York. You ought to get out as fast as you could.

There was no incentive or idea to stay in town?

No. Of course, I don’t know everything about everything, but I don’t think that anybody would put up a fight with me making that kind of declaration. And then there’s the whole legacy of Buddy Cianci, the mayor. Providence started the first arts and cultural district with incentives, where there were tax breaks given to artists and things like that. The first time that happened was in Providence under Buddy Cianci, the infamous mayor that spent five years in a gated penitentiary and who was very instrumental in helping me and helping AS220. He definitely got the idea that art and culture and entertainment could be a strong driver in this sort of reimagining and revisualizing of the city.

Now some of that came from some romantic idea that he was running to be mayor of Florence in the time of de Medici. And the other notion that came into his head is that someone had told him about Ireland providing certain tax breaks and incentives so that they didn’t continue to lose artists, to try to encourage them to stay in the country, mostly around the diaspora of their writers. He’d heard about that. He said, “Why can’t we do that?” And that’s how we ended up with the district with the tax breaks. And also at the same time, there was some pretty remarkable individuals. The architect, William D. Warner, who passed [in 2012], came up with the idea of opening up the river, so at the same time they were bubbling up the major public works projects, the reopening of the river and building this big river walk way [Waterplace Park], moving the train station, and eventually two years back we moved a highway. So there were these visionary public works projects that were also beginning to be discussed

This is all kind of taking place in the mid to late ’80s or so?

Correct. But at the same time, all the major music venues, Lupo’s Heartbreak Hotel, the Living Room, the Mad Café, all closed down at that time. Two of them reopened later, but at one point we were kind of holding the torch. I like to say that we were like the pilot light in art culture in the city that just wouldn’t go out whereas everything around us was. So we were filling a big gap even though we were completely illegal in what we were doing and our primary purpose from day one was to serve our local community and create a place that put the emphasis on process and the intrinsic value of artistic practice and of arts.

OK, so, in 1985 you find a building and you’re doing things like art shows and live music and performances. Were there any spaces or models you were kind of thinking about, or were you all imagining it on your own about pursuing the manifesto’s call for unjuried, uncensored art open to the public—how can we do that?

That’s a really good question because you need to understand that I came from a very working-class family. My father was an Italian immigrant, my mother was first generation Portuguese, and they worked in factories their whole lives. I had a lot of self -aught stuff about a number of different artists, this is how they started out, and was kind of a voracious learner around this whole art and music thing. Some people had exposed me to certain things, like Black Mountain College that happened in the ’50s in North Carolina, where all these artists met, like Rauschenburg and Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

So I knew about some of that stuff, but the unjuried, uncensored idea and environment, that came out of the process that I was engaged in. I knew things about the Salon de Refusés in Paris, and all of these alternative movements like Fluxus movement and Dada and Pataphysics, and I had become exposed to these kind of alternative arts and culture ideas, but the concept of a completely unjuried, uncensored venue where anything and everything could go—which I still think we need one of in every community in the world where people can convene and exercise their freedoms. I still think it’s a really important idea. That idea came through my personal experiences and process.

It wasn’t as if I was modeling it after anything because I still don’t know of anything quite like it that is completely unjuried and uncensored and has stayed that way over 30 years. And what in turn happens is what you create is a truly generative space that can’t help but stay current because it’s constantly being infused with new ideas by new young, crazy, wacky people, who I love to death.

Now, I can tell you that once we opened, there were a number of people and artists who came from other places, who had other experiences, and started teaching me about PS1 and P.S. 122 and La MaMa, etc., in New York. And I made some trips to New York to explore these places, but a lot of those places and pioneers in alternative art I did not know about until we opened a place and people started coming around saying, “Oh, did you know about this? Did you know about that?” And I ate it up. That was fuel, that was like people throwing logs on the fire, giving me the confidence that maybe this isn’t all that crazed.

When you first opened up in the ’80s, you mentioned you were kind of operating illegally. Did the city respond in any sort of way? Or were you kind of able to, because there wasn’t much else going on, operate without much fear of being asked for licensing or such bureaucratic things that often come up in doing enterprises like this?

Yes and yes. Yes, we were allowed to operate in this kind of historical moment where any life was welcomed, so there was somewhat of a blind eye. At the same time, the city did come by and said that, “We’re reading reviews in the weekly newspaper about performances and exhibits happening at this venue and we look and there’s no entertainment licenses, there’s never been a health department inspection, there’s never been a building department inspection.” And I got a letter.

And in those days the city was a different place, in the sense that if you knew people, there was a lot of work arounds that were possible, and I certainly capitalized on that. I went down threw a working-class fit at the license bureau, said, “I don’t need this shit anymore. I’m living in an unheated building, it’s the only thing going on in the city. You don’t want it? You don’t want to help me figure out how to get through this? Screw it!” And they said, “Who can we call?” I gave them a few names and a couple of people stepped up on our behalf. We made all of the loft studios that we were living in look like work studios. Inspectors started to come through. I think there was an understanding that they were to work with us.

We put up a few extra signs and the landlord built a second exit and then we’re on to our second landlord in a building that should have been condemned. And we continued to operate until the early ’90s when we decided that we couldn’t do this anymore and that we needed to own our own building and then we started mobilizing and talking it up and then people started introducing me to bankers and a lot of people. And again, this was another round of recession and a complete bank failure and banking crisis in Providence, so there was no work for contractors. Bobby Seale used to say that the Black Panthers were a social, historical accident and I think in many ways we do have to understand context and condition. You can have a great idea and it can be the wrong time.

And it’s so true. Some level of desperation can often open up people’s minds to different possibilities, particularly in the political and municipal world. My problem is that a lot of times what happens is there’s a certain amount of tolerance and forgiveness on the front end of it but then when people want to start investing, all of a sudden the rules change and then processes of gentrification and all this shit can start to create another problem.

You bring up a few things I wanted to ask you about. First, what made you all realize you that needed to move from being renters to being owners? Was that for the capacity to realize what you wanted to do with a building? Or were you recognizing that, “Oh, we want to stay here. We need to have a stake in our own sustainability”?

You keep giving me questions that have yes and yes answers. First of all, we were tired of living under the horizon and yet providing such an important service and set of opportunities. Also, our rent had tripled and they were starting to develop all around us, so we knew that our days were numbered. And by this time, I was well educated on the phenomena of Soho and other places where artists moved in and then this process began to evolve and occur. I think they have terms for this now like white washing and art washing, same thing.

By this time, we were fairly educated, we had contacts, and we realized that we need to own if we’re going to have any permanent sustainability. People had made some recommendations about moving into some of the communities where there was plenty of opportunity with properties and stuff. And I steadfastly, and others supported me, said, “No, we want a building downtown. We need to be central, so that it’s welcoming to people from every neighborhood community.” We stuck to our guns, though we had no money. No, we were not bankable, we were still fundamentally illegal even though we sort of jumped through a few hoops.

And the city showed us a building. And, listen, I used to say this, and I haven’t been saying it lately, but this [process of buying a building] was one of the most remarkable cons—of convincing people. It took such an effort on a few of our parts to be able to sell this idea, to get the bank to participate in everything. But, again, because of the state of the city, there wasn’t much else being proposed. So we got people to participate and we helped orchestrate a partnership loan that never happens, it probably hasn’t happened since, between the three banks in the city so they would all limit their exposure.

Oh wow, that’s impressive.

And we agreed to a lot of the sweat equity to keep costs down so that the project was financially manageable. And then, eventually, I went back to the city and got more relief from the city at different times when there was issues of cash and rewrote the terms to lower our loans so that stuff would be a little more forgiving on our behalf.

Our success had to do with our ability to hack the system. So, when we talk about hackers and people getting under the hoods and repurposing and rewiring, I think it’s very important for people in the arts and culture —or any movement, frankly, right now—I think that it’s important for people to understand the system, the organizations that we’re working with, and to be able to decode and understand how these systems work. We often take issue with a particular mayor or a particular person who’s a functionary within these systems when, in fact, the systems by nature are defective. And we need to be able to decode those things, understand their language, and, in essence trick the systems into believing we’re good for them—when, in fact, we are.

We have to learn the language, we have to understand where the resources are, we have to understand by who and how those resources are allocated, and then we have to make an appealing case for ourselves. And that’s a lot of responsibility and it’s a lot of hard work and requires a phenomenal amount of patience.

Is that something you’ve had to consistently do and adapt to as both people in those systems change and the surroundings change? I imagine as AS220 became more successful that it attracted more outside investment to the area. Do you find yourself having to play cards at a table where the pot keeps getting bigger because the people involved have more money?

The pot gets better and the competition does, too. More places open and art and culture is always sort of pitted against each other because there’s always crumbs on the table and we’re fighting to survive. That kind of creates a condition of competitiveness that is actually kind of unnatural to artists and makers because, by nature, we want to learn and collaborate. So, there’s a set of environmental conditions that you can’t deny and should be understood amongst people and I’m sure there’s little bits of competition between cultural institutions in Baltimore.

But I’m veering away from the question. The understanding and the decoding and being current on politics and policy and resources is something you have to be to survive doing something that’s in contrast to the dominant values of the culture, which is power and money, and you’re operating a set of values about access and opportunity and equity and shit like that. You have to understand and accept the fact that you’re up against it, which means you have to stay current on resources. There’s always money, but it shifts around.

It’s funny how it moves, it’s funny how the power of how that’s allocated changes and shifts, so one day arts organizations are looking for money from this big arts council, the next day they’re looking from their department of transportation. And that’s kind of what I mean, it’s that there are always resources to be allocated. Where they are? Who’s responsible for them? What are the different administration changes? They want to brand all of their actions with them and take credit for things. As things shift around, who do you buddy up with? Where does the money come from? What’s the expectations of that money? And what are the responsibilities and accountability to it? So, because of the limited amount of resources given the value added, it’s a field that you have to be pretty wily and pretty malleable.

And plugged in to what’s going on so you understand how those shifts are taking place.

You’ve got to show up to the neighborhood meeting. You’ve got to show up when the mayor’s doing some platform on art and culture and you got to stand in the front row and be seen. You’ve got to do that shit. A lot of people resent that and a lot of artists, in particular, resent that and that’s all well and good. You can resent it and you can sit back on your heels or you can decide you want to get something done.

OK, I know live/work studios have been a part of what AS220 has done for a while, so it’s something that you’ve been able to follow over a few decades now. How important is it for cities to have affordable living and studio space for artists when a city is trying to align itself with its arts and culture creators? And I ask because in order for artists to participate as artists in their cities’ economies, they have to be able to afford to live there. And we know development doesn’t just affect people’s abilities to buy buildings to create non-profit art spaces, it affects people ability to continue living in the place they call home.

It’s critical. I like to ask is art and culture a means to an end or is it a means to a means? Isn’t art something that you want, that vitality, that life, that dialogue that has been going on forever within any environment or community that you build and develop? So do you want art just as a means to an end, which is the short-term value that brings developers and bankers, or the long-term value to sustain a healthy, mixed-used, mixed-income community? The strategy unquestionably that I will not back away from is the idea of mixed-use, mixed income. That’s the responsible way of doing development. There’s absolutely no fucking reason why various classes of people can’t coexist.

So the only thing that gets in the way of that is our own fucking prejudices. If there’s any hope of this species for survival, we got to overcome that kind of shit and all of the other isms wrapped around with that class issue, whether it be racism, sexism, ageism, whatever the hell you want to talk about.

So to me, it’s always about mixed-use, mixed-income development, even in terms of my invitation to Baltimore. The first questions that I ask even of Ric [Royer] is, “Tell me about the demographics where you are and where this district where this building is. Tell me about the demographics. I want to know who lives there, home ownership, things like that.” Here’s a guy who’s starting an art’s organization and is trying to dedicate more and more of his life to just being an artist and I’m asking questions about demographics, because I don’t want to be that person that is somehow responsible in some way or another to displacing people. So, if we’re not going to displace them but we want investment, how do we do that?

I think that goes back to what you said about showing up and about understanding the policies that shaped the city you’re living in. Cities don’t look the way they do accidentally. People in power have made decisions that have led to the things we see being as they are, so being able to understand how you have to hack that to be able to reimagine a future that doesn’t require billions of dollars so you can displace people and build over their lives.

These are not new ideas, that people are afraid of what they don’t know and will react defensively and marginalize people based on their own ignorance. And that’s another part of the responsibility [of artist development]. I often talk about three spaces: physical space, virtual space, and conceptual space. How do you get an entire community to elevate its expectations of itself? How do you do that? We’ve done that in Providence. Now, I think it needs a fresh vision. I think we need to kick the whole thing in the ass in Providence and in the state, but I’m a very Providence-centric person. This is physical space, spaces where people can be people, where a community can engage with itself, where it can share, where it can have dialogue, and that’s AS220.

There’s the virtual space and I think there’s a new challenge around the virtual space in that it’s not enough just to provide access anymore. What do you do with that virtual space? How do you train people within the community to maximize the potential of this incredible resource?

And then there’s the conceptual space. How do we get people within a community to expect more of themselves and of their politicians and banks in terms of investment as partners? It’s so easy for the people that have access and the resources to dole out a few bucks and sit back and pass judgment as opposed to taking the totality of their experiences and knowledge and participate as partners.

And this goes back to—I hate to bring it up but I love to bring it up because I think it’s a good time to start reviewing some of the strengths and weaknesses of the ’60s. I think it’s a good time to sort of reknit those periods of time between the now and then. There was a lot of on-the-street, door-to-door kind of organizing then, and that’s where ABCD, asset based community development process, came about with the whole Dudley Street fight in Boston.

So, I think that if people really want to get down and dirty and really talk about how to serve communities and neighborhoods, it’s hard, hard work. And if you’ve been to one community meeting and had half the room screaming at you with sometimes unreasonable expectations, that for many people is the last time they go to one of those meetings. And it can’t be that way.

That’s just a reminder that grand ideas and talk and stuff like that only goes so far. At the end of the day it’s going to come down to people in a room deciding they want to do something about how tomorrow looks together.

That’s right. And maybe the times are getting ripe again where there’s so many people in so many different sectors pissed off right now, from housing to education to environment, maybe we’re going to see a little bit more of this. I know in the young people that I’m dealing with that there’s a whole new social consciousness that’s evolving that I want to be optimistic about.

*******

Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.

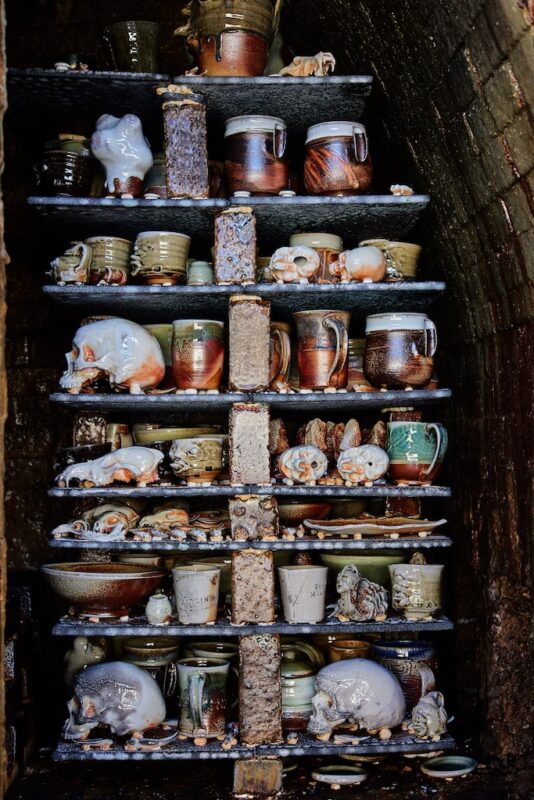

Photo Credits: Top Image by Jim Hooper and the rest from Bad At Sports.

Upcoming Events:

Le Mondo’s Birthday Party March 16, 404 N. Howard Street. Get tickets now!

On March 17 – BERT CRENCA TELLS ALL ABOUT ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICTS – tickets available at Eventbrite.