Catch one of these plays from Stillpointe, Single Carrot, Iron Crow, or Annex Theater before they close By Bret McCabe

This weekend presents a local theatergoing luxury that’s becoming increasingly common: there’s so much compelling theater happening at the same time that you’re not going to be able to hit them all. Three of these four productions—Iron Crow’s Fucking A, Single Carrot’s Samsara, and Stillpointe’s Grey Gardens—end this weekend. None of them are emotionally easy rides, which are part of the reasons they’re all such engrossing productions.

Stillpointe Theater shrewdly sees the misogyny lurking in the background of Grey Gardens. Roughly halfway through the first act, a rich, old, white guy offers some advice to the fairer sex. Major Bouvier (Barney Rinaldi), the portly mansplainer, is chatting with his niece Edie (Christine Demuth) and his two tweenage granddaughters, Jackie Bouvier (Anne Murphy on the night I attended) and Lee Bouvier (Avagail Hulbert on this eve). Yes, that’s future first lady and heiress Jackie Kennedy Onassis and her younger sister, the future socialite Lee Radziwill. The major counsels them that because “we live in perilous times, if you want to anchor yourself in an uncertain world you have only one recourse”—before launching into “Marry Well,” a jaunty little ditty driven by a coy, martial beat. The Major’s advice: “Find a staunch young patrician, Republican/ With the blood and the brains to excel/ Like the fine strapping lad your late grand mama had/ meaning I, little girls, marry well.”

Welcome to Stillpointe’s tartly comic and sweetly cruel Gardens, a production that understands that the story of Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale and her daughter Edith Bouvier Beale derives its gravitational allure from the lifelong détente of a mother-daughter relationship, and knows that these two women’s lives took place inside a social culture that didn’t want them if they weren’t going to do as they’re told. Co-directed by Stillpointe founding members Ryan Haase and Danielle Robinette, this production is the first to make use of the company’s pair of intimate performance spaces in the adjacent buildings at 1825 and 1823 North Charles Street, and it features two of its more formidable performers playing different versions of the same character. Also: puppets. All three of these decisions conspire to add a nuanced gravity to this version of the Tony Award-nominated musical—music and lyrics by Scott Frankel and Michael Korie, book by Doug Wright—that debuted on Broadway in 2006, and which The New York Times critic Ben Brantley called “a show that is, at best, costume jewelry.”

The source material here is, of course, filmmaking brothers Albert and David Maysles’ beloved, 1975 documentary about mother-daughter dyad that the filmmakers captured living in the decrepit decadence of the expansive, 28-room East Hampton estate that lends the movie its name. The elder “Big Edie” was a daughter of privilege who married lawyer Phelan Beale at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral in 1917. They lived on the Upper East Side, had three kids—two boys and one girl, also named Edith, aka “Little Edie”—and separated in 1931. Big Edie got Grey Gardens in the divorce, and it became the live-in rehearsal studio for her singer career. Pianist/composer George “Gould” Strong lived there for a spell; as did another male companion for a bit. By 1952, Big Edie was all alone, and Little Edie left Manhattan, where her own attempt at an entertainment career stalled, to return to the summer retreat they called home year round.

The two of them had been living there increasingly removed from the outside world when the Maylses showed up with their cameras in 1973 and captured a house overrun by cats, raccoons, trash, fleas, and disrepair. The documentary has stoked an adoring cult fanbase ever since, particularly among gay and queer audiences. “Gay men think they’re latching on to Grey Gardens because they think it’s camp, but it’s really because it’s about a parent-child relationship,” performance artist John Epperson, aka Lypsinka, told The Advocate in 2009, adding that “[t]he best movies are always about identity, and that movie certainly is.” Scott Frankel, the composer behind the musical Grey Gardens, told Newsweek in 2006 that “Little Edie’s so inspirational to a lot of disenfranchised people. . . . She somehow managed to put on some incredible headgear and still think the best years were ahead. She faced each day with optimism, energy and style.”

Stillpointe’s approach puts equal emphasis on both the parent-child relationship and the disenfranchisement. The musical’s first act plays a fast and loose with the Beales’ real story, remixing rumor and fact to imagine what life was life at Grey Gardens before the cats and trash took over. Twenty-plus years before The stunning, elegant big Edie (Zoe Kanter) is all posh enunciation, witty banter, silky gowns, and endless cocktails. She’s prepping the gorgeous Grey Gardens estate for Little Edie’s (Christine Demuth) nuptials with Joe Kennedy, and the extended family’s all there: Bouviers Major, Jackie, and Lee, groom-to-be Joe (Bobby Libby), and perpetually pickled piano man Gould (Adam Cooley), Big Edi’s partner in song and seeking distraction at the bottom of a glass. Big Edie in her youth also possesses a competitive, conniving streak, and her yearning for the spotlight, evening at her daughter’s wedding, sparks a schism that snowballs into a seemingly insurmountable chasm. If Big Edie can’t be happy in marriage, no one can, and the first act ends with Little Edie leaving Grey Gardens, never to return.

The entire audience for this Grey Gardens moved next door for the second act, where Big and Little Edie, and the state of the home, look like the decadent ruin familiar from the documentary. As exceptional as Kanter is with Big Edie in her youth, Danielle Robinette is ruthlessly human in her performance of Big Edie in old age. The use of different actors—in the original Broadway and Off-roadway production, Christine Ebersole played Big Edie in the first act and Little Edie in the second, which has a different effect—doesn’t merely highlight time’s unforgiving passage, it intimates how the social fall that accompanied it changes a person. Demuth returns as Little Edie, improvised head scarf an all. Save for a few visitors, such as nice handyman Jerry (Jon Kevin Lazarus), Big Edie and Little Edie live amongst their own filth, dreaming of what might happen in the world outside that isn’t ever going to happen. They were too brash, too opinionated, too liberated, had too many of their own ideas, didn’t just get married and do the wife thing the way they were supposed to. The narrative contrasts between the first and second acts shows that, yes, there was an insurmountable tension between Big and Little Edie that eventually tethered them together. The thematic contrasts between the first and second acts suggests that their resulting behavior because of that is what drove everybody but each other away. According to the society in which they traveled, they deserved their fetid fate.

And it’s one where they live surround only by a horde of feral cats, which Stillpointe features as puppets manipulated by everyone from the first act who isn’t in the second. These puppets lends a sweetly cruel touch; we see the Edies as haunted by the people who used to be in their lives when they had social connections, glamour, a future, money. Kudos to this production’s entire cast and crew for landing this quiet knockout punch. The story of Big Edie and Little Edie is, per the Grey Gardens documentary, an almost too textbook example of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s claim that there are no second acts in American lives—there’s nothing but the rise and the fall. Stillpointe’s approach to the unapologetically mainstream musical Grey Gardens reminds us that those rise and falls in America don’t happen in a vacuum, they take place in the socioeconomic milieus that people make. And if this is how America’s finest families—who attend the finest schools and go on to be captains of industry and the government—treat their own when they don’t do as they’re told, well, how do we expect they’re going to treat anybody who isn’t white, privileged, and rich?

When Craig—and only Craig—flies to India for their child’s birth, all metaphysical hell breaks loose. The wise-cracking, relentlessly inquisitive Amit (Utkarsh Rajawat) appears to Suraiya, a projection of the unborn fetus she’s carrying. Katie begins having visits from the Frenchman (Dustin Morris), a projection of the suave, seductive leading man her mom idealized. Nobody seems quite prepared for—or completely thought through—what a Western couple paying for a child produced in a south Asian country means. And they better figure it out soon, because Amit is ready to come out—that is, until Suraiya talks to him about the cycle of life, which eventually includes death.

Director Lauren Saunders and scenic designer Jason Randolph opt for a minimally surreal visual approach. The set is but a curved screen hanging above a curved set of risers that can be moved into a variety of positions. While the dramatic action cross cuts between America to India, only the characters change. Everything takes place in this visual sea of neutral hues, as if the imagination had been decorated by the Pottery Barn.

I suspect that’s intentional: tone-wise, SCT’s Samsara feels a bit like a very special episode of an otherwise anodyne prime-time television drama. As such, the acting is intentionally affected, as if characters are having experiencing seemingly obvious points—about life, their childhoods, the global movement of capital, marriage, colonial exploitation, babies—for the first time. It’s a cheeky way to spotlight how superficially mainstream entertainment typically handles serious topics. Diem and Tharmarajah, especially, ride this knife-edge balance of naiveté and knowingness, finding the sincere emotions among the superficial reactions. Rajawat has a gift for oddly timed humor, blending the total lack of knowledge, much less consciousness, you’d expect from a, well, fetus, with a wily wiseacre streak. He’s not just a fetus trying to form an opinion; he’s almost surly about it, too. Also: Fenhagen is a total badass at creating the upwardly mobile middle-class American white woman whose anti-anxiety mediated understanding of the world she’s formed in her head you will have to pry from her cold, dead, organically eating, credit-card wielding, thin hands.

The kicker is that Samsara can’t avoid heading into more serious terrain, because things like the global movement of capital and colonial exploitation and, well, birthlifedeath don’t conform to the unreality perpetuated by mainstream entertainments. This intermission-free, 90-minute play takes a turn toward the end that might feel sharp, but it’s merely what’s always lurking behind the perceived consumerist benefits of contemporary capitalism, a reminder that the relative ease of being able to click and buy anything online only temporarily shields us from an entire system of unpleasantness and exploitation that isn’t going to end well, no matter how rosy things appear right now.

The Tempest doesn’t so much have a plot as it has a suggestion of things that take place. Prospero (Aladrian Wetzel), the former Duke of Milan, and his daughter Miranda (Katharine Vary) live on an island deserted save the deformed creature Caliban (June Keating) and the spirit Ariel (Mika Nakano), with who Prospero communicates. Prospero conjures a storm to crash the ship carrying his brother Antonio (Betse Lyons), the king of Naples Alonso (Sarah Lamar), and his retinue—Stephano (Molly Margulies), Alonzo (Sarah Lamar), Gonzalo (Michael Ziccardi), and Trinculo (Carly Bales)—washing them ashore. The King believes his son Ferdinand (Jonathan Jacobs) is dead, but he merely washed ashore elsewhere and is found by Miranda. What ensues is the kind of small alliances formed for potential power grabs that run through Shakespeare’s plays, only with a little sorcery thrown in.

All praise Annex’s back house with this show: the world created by set designer Douglas Johnson, costume designer Susa MacCorkle, and lighting designer Chris Allen, composer Rjyan Kidwell, and video designer Tom Boram feels closer to psychedelic late 1960s/early 1970s European flicks than anything in the Shakespeare universe. Wetzel’s Prospero—who stumbled a bit early on with Shakespeare’s odd language the night I saw this, but she recovered strong—is clad in a white body suit with fringe and feathers and faux fur things and flowing cape that’s just cool; she looks like she wandered straight out of an Alejandro Jodorowsky flick and into a Baltimore underground theater, bringing a layer of wiggy ’70s excess with her. Nakano’s Ariel flutters around the stage like some newfangled bird-bug species. And Keating’s Caliban costumes turns the character into a tentacled humanish creature ripped from the pages of a Japanese comic.

Most entertaining of all is the drunken partnership formed by Margulies’ Stephano and Bales’ Trinculo, who are plotting something but are really more interesting in tying one on. Stage inebriation is one of those things you think should be easy but more often than not just looks idiotic. Bales and Margulies appear to know that the drunken verisimilitude passes directly through outright idiocy. This pair of bumbling, tumbling, stumbling, and slurring actors should do an online web series where they, in sloshed character, read House and Senate Democrats’ reasons for voting “yes” for Trump’s cabinet appointments—because the only excuse such spineless officials could possibly have for such is that they were obliterated beyond all human thought.

Lori-Parks’ Fucking A, which debuted in 2000, is an allegorical reworking of The Scarlett Letter, set in mythical small town, where the Hester (a powerhouse Jessica Bennett) branded with an “A” is the local abortionist. Hester used to work for the mayor (Jamil Johnson) and his wife (Cricket Arrison), until her son supposedly committed a crime that sent him away and cast her to the lowly job she occupies now. Hester is quasi-friends with a prostitute Canary Mary (Deirdre McAllister), who’s sleeping with the mayor, and the Butcher (Jared Swain), who dotes on her on a bit. Illiterate, Hester relies on Mary to read the letters from prison her son mails her, and the local scribe (Rebecca Dreyfuss) to write her replies. With what little money she brings in from performing abortions, Hester pays into the Freedom Fund that, she hopes, will get her son out of jail after 12 years.

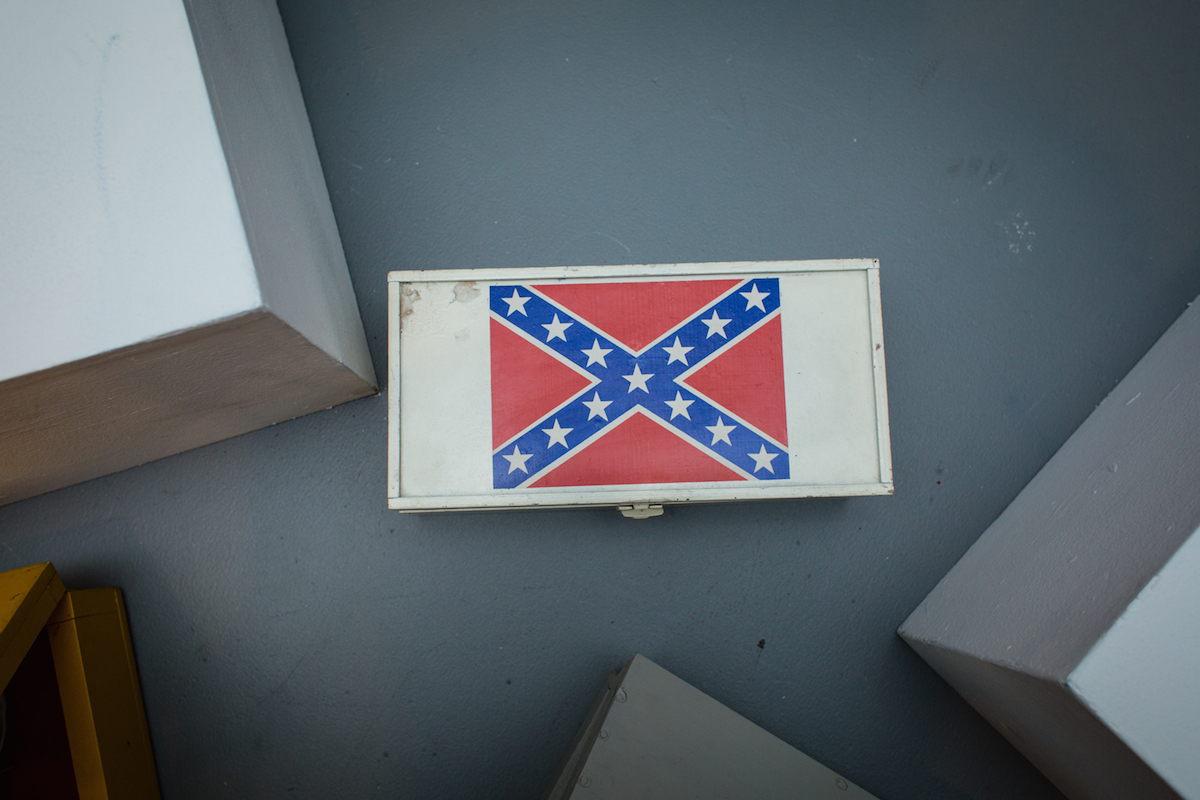

That simple sketch suggests a level of conventional dramatic reality coursing through Fucking A that the script flatly rejects. There’s enough recognizable figures and ideas floating around—a mayor, a butcher, some pantomime of ethics and morality—that you sense a patina of a Wilderesque Our Town going on. But other elements short-circuit that assumption. For one, a string band—percussionist Josh Eid-Reis, mandolinist Dave Engwall, and guitarist/banjoist Kevin Krause—sits onstage the entire play, providing some musical accompaniment and providing background when characters ocassinally break into bluesy, folksy songs. At times, Hester and Canary Mary speak in an invented language that a voice over translates for the audience. Also: the level of violence accepted by everyone in the play is, well, unconscionably unacceptable. When a feared convict called the Monster (Javier Ogando) escapes from jail, a trio of red-neck hunters (Caitlin Weaver, Kelly Hutchinson, and Martha Robichaud) set off to track him down and capture him, dead or alive, for a bounty. The bodily cruelties they inflict on escapees, such as cutting off limbs while still alive? They do those for free.

Anybody slightly familiar with Jacobean tragedies that inform this play will have an idea just how true horrorshow this will go before it’s all over; what director Stephen Nunns and set designer Nicki Seibert add to that rough ride is a withering indictment of state law and order. The stage is set up like a shotgun shack judge’s bench, with a series of moveable tables, bars, and a bed that create various interior rooms right in front of it during the production. A porch swing occupies stage right, a sofa stage left. The entire cast sits somewhere on this stage for the entire running time, turning the entire performance area into a courtroom into the players of a trial with the audience as the, well, audience.

Or does it? As Iron Crow’s blistering Fucking A unfurls, in the back of your brain you start wondering, Who’s on trial here? Is it Hester, being judged by the town of her peers? Is it the Monster, whose word-of-mouth actions since escaping flee from the lips of everybody, though we never see him do what they accuse him of? Is it the mayor, the ostensible man in rich man in charge, who’s position it is to guide the state through the exercise of its power. You decide. By the time this Fucking A, I wondering if the play might be indicting those people who sit quietly and comfortably watching a world lead itself to ruin for the sake of its own entertainment.

******

Author Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.

Stillpointe Theater’s Grey Gardens runs through Feb. 12; tickets. Single Carrot Theater’s Samsara runs through Fe. 12, tickets. Iron Crow Theater’s Fucking A runs through Feb. 12; tickets. Annex Theater’s The Tempest runs through Feb. 19; tickets.