Laying-by Time: William Christenberry at MICA by Amber Eve Anderson

“The aging process, what I call the aesthetics of aging, has always impressed and intrigued me,” said artist William Christenberry. This aesthetic is the focus of a comprehensive solo exhibition curated by Kimberly Graham of the recently deceased DC-based artist.

Christenberry’s work is rooted in his summertime trips to rural Hale County, Alabama from nearby Tuscaloosa where he lived during his childhood. After moving to the East Coast, he discovered Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—a book of photographs by Walker Evans with text by James Agee about the rural poor of Hale County during the depression. This place became a site of pilgrimage throughout his life and the subject of much of his work. On view in MICA’s Decker Gallery through March 12, 2017, Christenberry’s paintings, photographs, sculptures and an installation try to make sense of the distant south of his childhood.

Laying-by Time, the title of the exhibition, is named for the six-week period between the last of the farmers’ work in the cotton field and picking season. It is a time of forced respite, filled with anticipation.

The best works in the exhibition are those that depict the passage of time, or rather, its effects. The change of seasons: a building photographed in summer is consumed by kudzu, but then bares its form in the stark, grayed surroundings of winter; three thermometers “Found Near Moundville,” each more rusted and weathered than the one before; a sign advertising Royal Crown Cola weeping its blue dye into the hand-painted letters below stating ‘Bread of Life.’ The aesthetics of aging plays out profoundly upon two buildings to which Christenberry returned repeatedly over many years: the house at Christmastime and the BBQ Inn.

Found Near Moundville – Three Thermometers

Found Near Moundville – Three Thermometers

Christenberry first discovered the “House at Christmastime” in 1970. “Just outside of town, on a rise in the landscape, was this house, a very simple rectangle, with two front doors. It was very crude, but it had aged just beautifully,” he said.

He returned to photograph the half-painted building in 1971, 1972, 1974 and 1976. Through the years, the surroundings remained more or less the same, the house remained half-finished. “Then I went back in 1977 and the house was gone,” Christenberry said. “The dwelling was completely gone, like it never existed. There was no evidence of it having fallen down or anything like that. It was gone, and there was only a field of grass in its place.”

The same fate was in store for Christenberry’s other beloved building, the BBQ Inn. At MICA, a grid of 16 photos of the BBQ Inn portrays the same storefront over a period of twenty years, the sky overhead shifting through grays and blues, the windows shuttered, the signage fading, the porch roof beginning to collapse. The final photo depicts only a cement pad at the corner of the same intersection, a space to mark what once was.

BBQ Inn Series

There is a mystery to the aging process, whether in buildings or in oneself, that ultimately results in loss. These photographs serve as a document to that process and their strength lies in their observational quality, as proof that such a building in such a place existed. Perhaps they also served as a reminder for Christenberry himself, as he matured in faraway DC, of the rural, the slow, the dying, a visual aid to the expansiveness of distance and time.

All of Christenberry’s images retain the distance of an observer, and render us as outsiders. Distances can allow for a certain clarity, but ultimately, distance haunts this exhibition.

House at Christmastime sculpture

House at Christmastime sculpture

“House at Christmastime” became a sculpture true to the original image, half-painted and shabby under the artist’s hands. Made from balsa, bass, and pinewood, the dollhouse-sized structure sits atop red soil in a birch plywood substructure. Only one window is left open to expose the darkness inside, an apt metaphor for the nearby “Klan Room Tableau.”

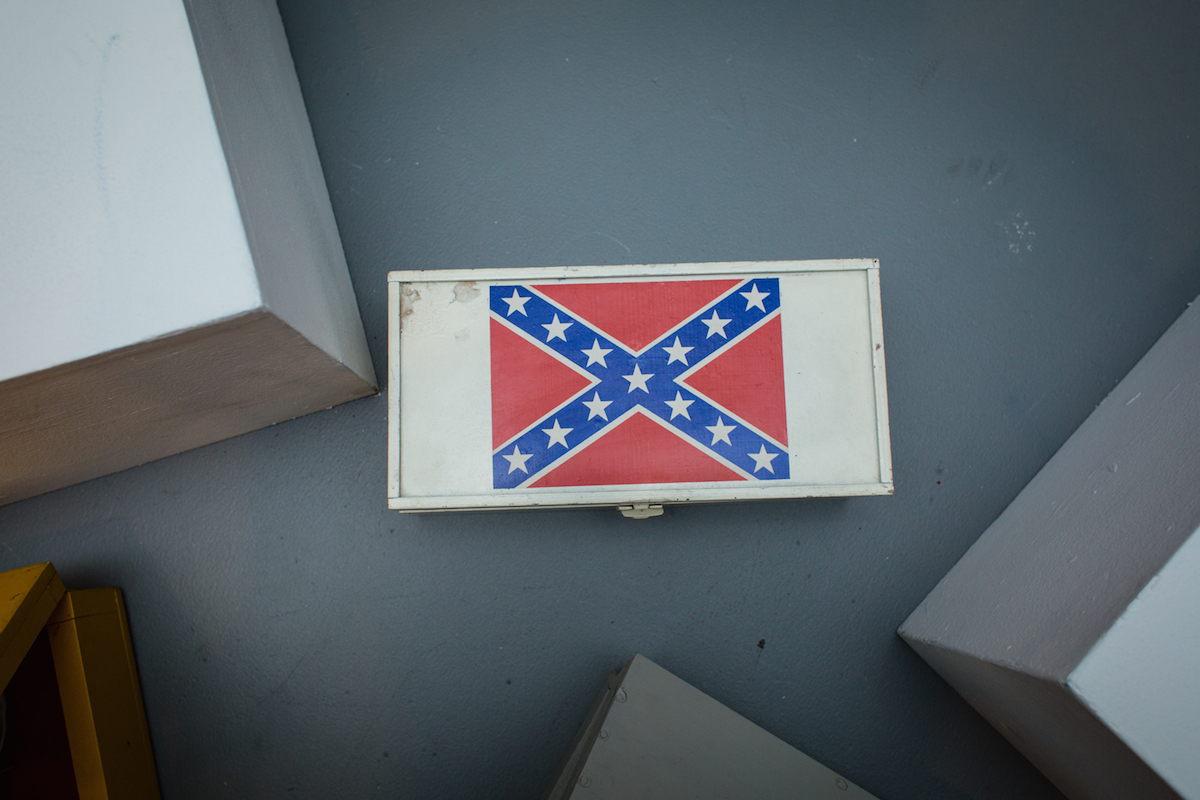

Rarely exhibited, the dense, room-size installation is made up of more than 400 individual pieces. Dimly lit, a glowing neon cross hangs high on the wall, front and center. The room is Christenberry’s nearly lifelong dedication that stems from an attempt to attend a KKK meeting that he immediately fled. Hooded dolls are wrapped in string hanging from walls and small branches. Other hooded figures lie in coffins or inside yellow display carrying cases lined in green or red felt. Drawings and photographs of these dolls line the walls alongside signs advertising Klan meetings and confederate flags.

The critical distance of the observer in such an installation is misguided. The sentimentality of childhood attachment to a place can hardly be reconciled with the existence of the KKK in that same realm. In a two-minute recording beside the doorway to the installation, Christenberry says that he was “very affected by segregation” and that while he had heard of the Klan, he had never seen it firsthand before attempting to attend the meeting.

Klan Room Tableau – detail

Klan Room Tableau – detail

The installation indicates a lifetime of trying to make sense of a darkness he couldn’t quite grasp, yet it offers no conclusions. The room forces the viewer to confront this darkness, to welcome the wave of unease that Christenberry himself describes it as “very, very intense,” yet given the overtly racist paradigm of the Klan, such an installation demands a moral response. Here, it is merely placed behind a curtain, left inside a darkened room, to be passively observed, yet allowed to fester and grow. Distance here is equivalent to isolation.

Like the buildings he focused on as isolated objects, facades as relics of time passed, Christenberry’s “Klan Room Tableau” installation room offers a view of American darkness, more easily ignored than confronted, a unique privilege offered to white citizens but not people of color, and offering a flawed and problematic distance.

In 1979, before the “Klan Room Tableau” had ever been exhibited, it was mysteriously stolen from Christenberry’s studio. This led to a series of sculptures titled Dream Buildings, early versions which were windowless cubes with dramatically peaked pyramids on top, reminiscent of both church steeples and Klansman hoods. The exterior of “Dream Building II” is peppered with miniature signage that reads “Prepare to Meet Thy God,” “Jesus Saves,” “666,” “Coca-Cola,” and “7-Up.”

Dream Building II

Dream Building II

The building asserts a desire to reconcile the religious with the commercial alongside the dark underpinnings of both. In the nearby Brown Center atrium sit two larger Dream Building sculptures. These forms retain the hooded pyramid, but are taller, more monumental forms with bars around the lower exterior. They remind me of many of the monuments in DC, where Christenberry lived. They serve as a reminder of the influence of the Klan on political, as well as religious, institutions, no matter how distant that influence may grow to seem.

I found myself returning to the exhibition, much like Christenberry himself returned to Hale County, looking for answers, but finding none. There is a fundamental failure in Laying-by Time as an exhibit: the way the exhibition sidesteps the huge social issues at hand, just like much of white America continues to do today. It’s not enough to merely put its artifacts on display to prove their existence; the inability to name the elephant in the room sucks much of the energy from this exhibition as a whole.

Through the process of aging, the place of Christenberry’s childhood must have taken on a different hue and nostalgia can be a form of melancholy. However, there is a deeper meaning underneath all of the symbols he depicts. After the laying-by time comes the harvest. Only by naming a thing honestly can we see its demise.

***********

Author Amber Eve Anderson is a Baltimore-based multidisciplinary artist whose work uses images, objects and language to explore themes of place and displacement. She is a recent graduate of the Mount Royal School of Art MFA program at MICA.

Laying-by Time: Revisiting the Works of William A. Christenberry is on view at MICA’s Decker Gallery through March 12, 2017.

An Intimate Window: Gallery Walk & Talk with Sandy Christenberry

Wednesday, February 22, 2017 @12pm in Decker Gallery, Fox Building, MICA

Generating Conversations: Against a Backdrop of Contemporary Concerns

Monday, February 27, 2017 @7pm in Falvey Hall, Brown Center, MICA

Quotes are taken from William Christenberry: Working from Memory compiled and edited by Susan Lange.

Photos are open sourced from Art.net and not necessarily those in this exhibit.