Developing a Bullshit Detector by Benjamin Andrew

It’s been a long time coming, but 2016 has seen the traditional news media wither under the power of social media, with politics-as-usual finally replaced by pure showmanship. These factors and others have created a vortex of utter disregard for what’s real and what isn’t.

Almost as common as the fake news stories they protest are the opinion pieces by journalists and scientists worried for their professions. As if nationalist extremism weren’t enough, the age of reason itself seems poised to collapse under the weight of this global angst.

Playing along, let’s assume that truth is finished: recall that artists and writers have been trading in make-believe forever. How should creatives deal with this particular steaming pile?

Mere days after Donald Trump secured the presidential election, the Oxford English Dictionary declared “Post-Truth” their Word of the Year (although it was decided prior to November 8). It’s an awkward word that’s hard to use in a sentence, but sure enough, concerns have broiled after the election about the spread of fake news on social media. The OED’s decision has succinctly summed up the zeitgeist of bullshit that plagued the 2016 presidential campaign and the media world at large.

A national poll released on November 2, 2016, revealed that Trump was seen as more honest than Hillary Clinton by an eight-point margin, this despite the fact that he was averaging 20 lies-per-day according to the diligent bookkeeping of Daniel Dale, who recorded a grand total of 560 lies uttered by Trump throughout the campaign.

I’ve always seen Trump as a media savant; his maxim of “fuck it” made him unstoppable in debates rooted in logic, and his disregard for facts succeeded so well because it was at the center of a media world obsessed with the same.

Ubu Roi from Jean-Christophe Averty’s 1964 film adaptation

Ubu Roi from Jean-Christophe Averty’s 1964 film adaptation

It’s been well reported that Facebook and Twitter are chock full of fake news, which is unfortunate since Pew Research discovered that’s where 30% of U.S. adults get their news. More troubling is a separate report from Stanford that revealed 82% of teens can’t tell the difference between sponsored content and genuine articles.

Even when a young person miraculously clicks on content from a major newspaper or television network, journalism has become more focused on emotional, subjective reporting, and harder to tell apart from op-eds —plus readers can always stick their heads in the sand. Peter Pomerantsev imagines Trump voters asking, “If all the facts say you have no economic future then why would you want to hear facts?”

Trump succeeds partly because he is brave enough to offer plainly disprovable statements alongside true ones. He lies about big, obvious facts (“a day prior to birth you can take [abort] that baby”), but also small facts that he plainly knows are false (Palm Beach, FL is “probably the wealthiest community there is in the world”), correctly betting that most people don’t care. Trump lies so much that he needs to assure his Twitter followers of his authenticity with his @realDonaldTrump handle.

The false equation of lies and facts is commonly used by autocrats like Putin, and was also featured this year in the Brexit movement, when it was falsely publicized that the European Union was taking £350 million from the UK each week. Surprisingly, Pomerantsev traces this effect back to critical theory:

“This equaling out of truth and falsehood is both informed by and takes advantage of an all-permeating late post-modernism and relativism, which has trickled down over the past thirty years from academia to the media and then everywhere else.”

I would wager that many contemporary cultures are informed by the ideas of avant-garde theorists and fringe artists, but is postmodern theory really to blame for 2016’s post-fact meltdown? Was it the liberal artists and writers all along?

One warning sign from the creative industry was Stephen Colbert’s notion of truthiness, which he defined in his Comedy Central show as “believing something that feels true, even if it isn’t supported by fact.” The word combined politics and folksy wisdom for a prescient joke that was recognized as the 2006 OED Word of the Year. When introducing the word, Colbert said:

“Now I’m sure some of the word police, the ‘wordinistas’ over at Webster’s, are gonna to say, hey, that’s not a word… Well, anybody who knows me knows that I’m no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They’re elitist! Constantly telling us what is or isn’t true. or what did or didn’t happen.”

Unfortunately Trump’s claims of leftist mud-raking aren’t made with the same wry smile that kept Colbert grounded in reality.

The Colbert Show, 2005 [via Comedy Central]

The Colbert Show, 2005 [via Comedy Central]

Ironically, the bulldozer of postmodernism was intended to level the playing-field and discredit the stalwarts of Western culture. Satire like Colbert’s evolved to highlight the impossibility of fixed truths and to cut apart traditional authorship, all while increasing the diversity of creative fields by telling stories from myriad vantage points. Now that anyone can create facts by posting fake news articles or editing Wikipedia, the radical has been subsumed into the media sphere. Reality television and mockumentary sitcoms like The Office have conditioned audiences to assume that everything is a show — their own lives posted on Instagram as carefully rehearsed vignettes.

I feel particularly invested in this debacle because I’ve spent a number of years working in the obscure genre of Fictive Art, or art that uses imaginative narratives as a medium the way painters deploy oils. Artists working in this vein use photographs, text, installation, and web design to craft stories that often appear completely realistic at first blush.

Eve Andree Laramee curated an exhibition in 1997 of the collected work of Yves Fissiault, a Cold War engineer turned artist who she invented as farce. The New York Times reviewed the show without catching on to the joke, and validated Laramee’s studious merger of fact and fiction. As a sort of acting experiment, she made paintings and sculptures as Fissiault over a period of six months.

Other artists have adopted personas, but there is a unique breed of storytelling done by artists obsessed with explanatory labels and biographies. Their goal isn’t deception, so much as reveling in the narrative impulse by using every tool at their disposal. The Yes Men inject satirical what-ifs into corporate culture, connecting with audiences who don’t even know they’re encountering art. Fictive artists have even designed whole fictional institutions like the Museum of Jurassic Technology (David Wilson’s storefront mystery box in Los Angeles).

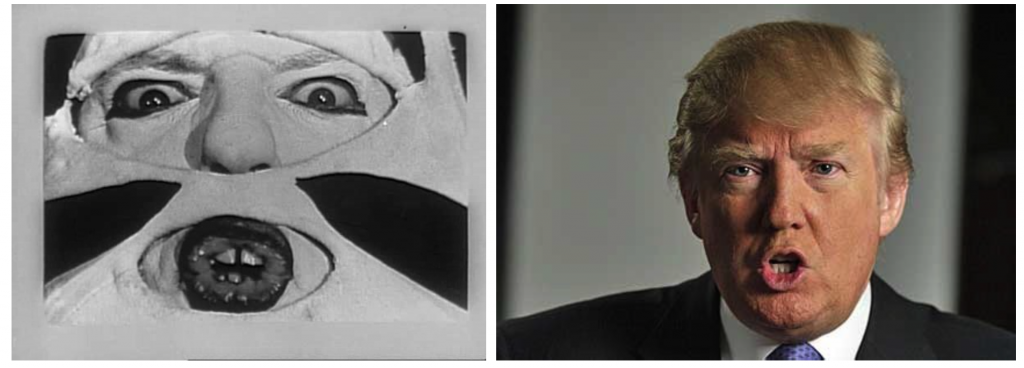

The real gist of fictive art lies at the confusion of creative work with real life. Consider Alfred Jarry, a 19th century playwright who spent years creating an outlandish public persona inspired by a character from his writing: the mad dictator Ubu (who was in turn based on Jarry’s childhood teacher). Jarry made his life into a literary fiction by adopting a mechanical speech affect, imbibing terrific amount of alcohol, wearing paper shirts with painted-on ties, keeping owls in his half-floor apartment, and carelessly discharging firearms to light cigars and hunt frogs in the streets of Paris. Historian Robert Shattuck described Jarry as offering “the sacrifice of his life to a literary ideal.”

The calculated merger of Jarry’s life and work extended to characters in his writing: many experiencing doubts about reality, or exhibiting psychic powers to control the laws of physics. That attention-grabbing personas have become a mainstay of contemporary media is not surprising, but the deliberate oafishness Jarry adopted to embody the mad king Ubu is striking in light of the recent election. In a logical extension of current politics, the College of ‘Pataphysics that Jarry inspired nominated an African crocodile as their Vice-Curator in 1978.

Left: Ubu Roi from Jean-Christophe Averty’s 1964 film adaptation [via Atomic Caravan] | Right: President-Elect Trump [via trumpmouth.com]

Left: Ubu Roi from Jean-Christophe Averty’s 1964 film adaptation [via Atomic Caravan] | Right: President-Elect Trump [via trumpmouth.com]

Ubu was a pompous caricature, and Jarry’s affectations were a satire of a satire. Sadly, Donald Trump has not turned out to be Andy Kaufman in disguise, though Newsweek ran an investigation on the matter to clear up any lingering doubts that Trump’s campaign was a joke all along. Part of me still hopes that on the day of his inauguration, Trump will walk away from the podium laughing. His entire campaign could be interpreted as a satirical execution of political precedent, a thesis statement on media studies that might please Karlheinz Stockhausen who notoriously described 9/11 as “the greatest work of art imaginable.”

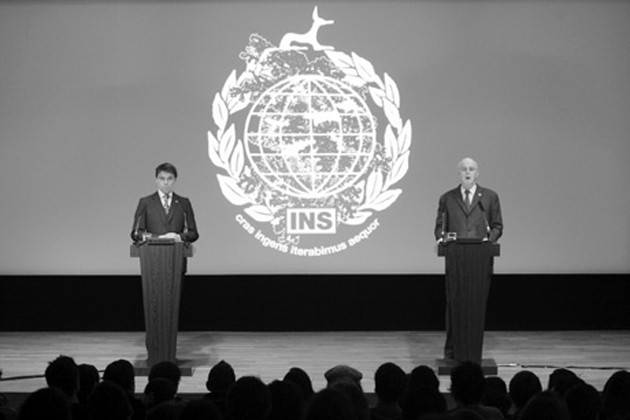

Another media experiment from the lineage of Jarry is Tom McCarthy and Simon Critchley’s International Necronautical Society. For years, the pair have published rubber-stamped reports that use the language of avant-garde manifestos to “map, enter, colonize and, eventually, inhabit” the concept of death (hence, “necronautical”). Their writings are immensely dry and reach the pinnacle of academic humor if you can get through the tongue-in-cheek bombast.

In light of Trump, it’s worth taking a look at the public performances of the INS that McCarthy and Critchley have staged at various art spaces. Standing before a UN-inspired emblem, the two don suits and ties to look the part of true society men, updating last century’s manifesto declarations with the blase rigor of today’s media landscape — only it’s not them; the events are often performed by actors to further fictionalize their invented society.

International Necronautical Society [via Triple Canopy]

International Necronautical Society [via Triple Canopy]

Are fictive artists poised to flourish in a post-fact society? Visionary artists and authors of meta-fiction certainly have the imaginative chops to craft the best lies in the game, but should they? When scientists and historians are seriously concerned about the waning of truth, is it responsible for artists to smudge the line between fact and fiction?

Honestly, art isn’t going to overturn fascism on it’s own — after all, the country’s creative industries rallied uniformly behind Clinton and look where that got us — but artists need to keep their fires burning, so they may as well reach out with their work and utilize their expertise in the realm of imagination.

Work like McCarthy and Critchley’s INS seems designed to be completely inaccessible to most people. Who is going to read a ten page manifesto purposefully written to appear dry and stodgy? The meta-narratives and references hidden within fictive art are like candy for the puzzle-obsessed, but go unnoticed by anyone who hasn’t read the prerequisite essays, and, more importantly, doesn’t know they’re playing a game in the first place.

In a post-fact world it will be vital for artists to be truth tellers, but fictive art can still illuminate through riddles.

Young people can no longer identify accurate information from the muck, but they won’t learn how to do that without practicing their own detective skills. Part of the education needed for a progressive electorate is the ability to solve problems, to examine information and arrive at judgement.

Artists are already great at this, but through inclusive fictive art, storytellers can establish mental challenges that deceive for the sake of humanist inquiry rather than for selfish profit. Even an abstract painting can provide this sort of challenge-space for its viewers, artists just have to respect audiences enough to let them figure out the work and offer them something recognizable for them to grasp onto. Fictive art rightly embraces the varied technological formats of its time to play its games. Moving forward, artists just have to make sure everyone is invited.

*******

Author Benjamin Andrew is an interdisciplinary artist exploring new media storytelling and DIY science. Check out his work at benjaminandrew.net.

This story was originally published at medium.com.