An Interview with Patrick McDonough by Paul Shortt

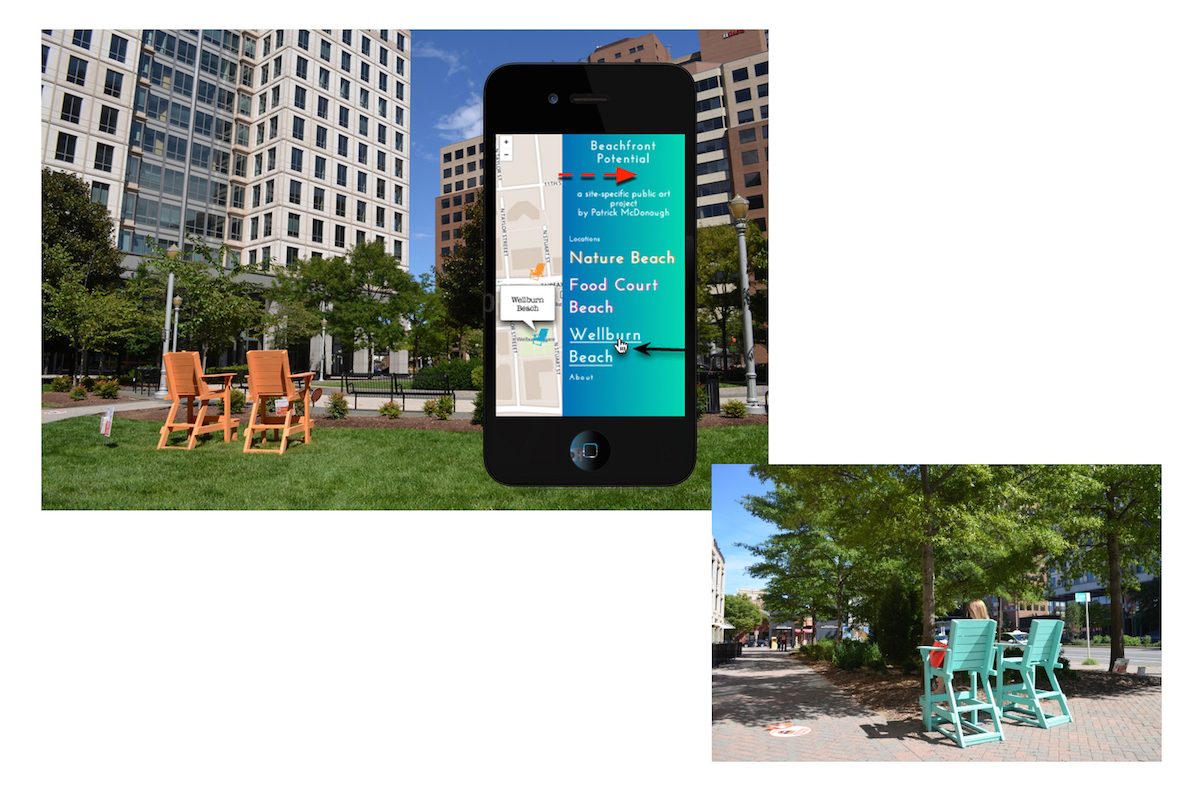

Patrick McDonough is a visual artist concerned with popular definitions of public space, the environment, and leisure. His artwork often deals with displacement, such as in White Turf Painting Actions, where he covered an entire field in white turf paint creating a snowy landscape, and Beachfront Potential, in which he created giant beach chairs to sit in and wait for sea levels to rise.

In his work, function, play, and structure often combine often in incongruous ways, such as in Awning Studies presented at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, NY where he created awnings minus their architectural structures or his Lawn Chair Series where formalist works mimic lawn chair webbing. McDonough’s work moves from public art to gallery exhibitions, often creating immersive environments inside and out. The artist currently teaches at American University, GWU, and McLean High School, and previously worked at ConnerSmith gallery in DC.

He generously offered to sit down and discuss his current projects and ideas.

Paul Shortt: In our studio visit you mentioned that you had been reevaluating the stakes of your art practice and that your were currently rethinking your approach. Can you talk a bit about this?

Patrick McDonough: I think it all started with a sequence of events that occurred in the summer of 2014. I had just returned from working on a project in Miami, my wife and I had closed on a house that needed some serious love, and I was at my studio – at the time near DC’s Union Market – picking up some tools. The developer who was renting us the space happened to walk in the same morning to say we had two months to move.

Now this was a special case because the landlord was willing to help me and the three other artists in the space find a new location. But it was only guaranteed for a year. So I ended up asking myself, can I do this again? That would have made for four studios in five years for me. PLUS I was on the docket to teach five classes that fall! Ultimately I decided to put my work and materials in storage and attempt to, as you say, reevaluate how I wanted my work to proceed.

This reevaluation came from my realizing that ever since grad school I had been careening from one project to the next, and from one studio to the next, and hadn’t ever had the chance to widen the zoom I had pointed at my own work. Don’t get me wrong, I was super fortunate to have had the opportunities I had, but I felt like I needed to pause and make some sense of what I was really up to.

And now, a year and a half or so out from that, I am really glad I did pause. I’ve had a chance to question my own ideas of how to structure an art practice sustainably – where work can be made, where ideas can be contemplated, when time can be carved out. Not only that but I have had the chance to refocus on the elements of my work that I believe are most relevant.

A recent example of this is my return to foregrounding concepts of leisure in current and forthcoming projects. This was a content area I was utilizing when I first finished grad school, and I found that I had become hesitant to invoke the term as the years went on, though it was still present in my work in some way. Having had a bit of time for self-reflection however, I have returned to grappling with the radical or socially responsible opportunities present in non-work, non-self, and family care time (i.e. leisure). This type of time is not only extermely contested by our distraction-based, unequal economy, but looks to me to be where we have the chance to compromise the least – through political and volunteer activities, cultural participation and production, organizing, gardening, etc.

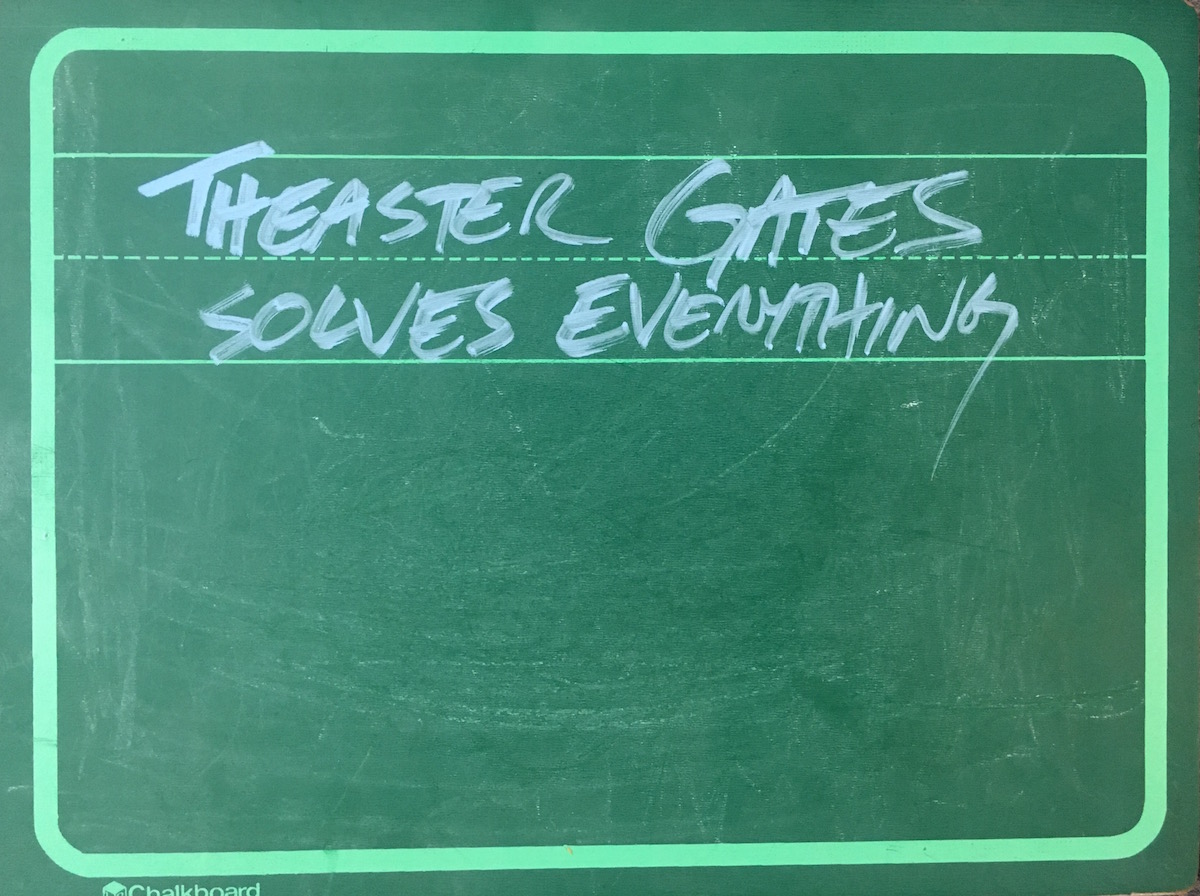

A sketch that stuck out to me in your studio was a chalkboard piece that says ‘Theaster Gates Solves Everything’? Can you talk a bit about his model of making and the problems and strengths of it?

So I have to first admit to having never had a chance to attend an event at Dorchester Projects or the Stony Island Arts Bank. When I was last in Chicago I tried, but it was on a Monday (and before the Arts Bank had opened), so nothing was going on. In general I find myself endlessly fascinated by Theaster Gates, in some kind of love/befuddlement way. I teach his projects whenever I can just to have as many chances to discuss it as possible. Overall I find him to be a pied piper for the role that art and artists can play in cities and in the machinations of grassroots politics, perhaps completely transforming the way artists get invited to the table – so long as he gets to sit in the chairman’s seat.

Having a seat at the table is essential. I think that’s why I was struck by your sign about Theaster. He’s the big name artist of the moment to bring in, but that doesn’t mean he’s either the right artist to be there, or that he is going to save the day.

Ultimately there are a series of questions/concerns that Dorchester/Rebuild raises for me – and that apply more broadly. Do we care where the money comes from?

(Most) art and artists vociferously tout the progressivism/independence of their projects and practices yet these ideals for the most part don’t extend to the notion of where the capital inputs appear from. Or maybe it’s a fool’s errand and this is capitalism and the money is all dirty. A few thought experiments though:

- A young artist gets a phone call from a dictator who wants to buy their whole studio. Should they say yes?

- A socialist-leaning curator works for a public art production company in a major city that receives large support from ravenously development minded real estate moguls. Should we care?

- A social practice artist produces project in culturally underserved neighborhoods, with help from a mayor who is closing public schools in the same neighborhoods. Can the artist speak out?

- How or should artists align themselves with power? Does change come within a la Hillary Clinton? Or through revolution a la Bernie Sanders?

- Do stated claims versus actual outcomes matter? For instance, until the Arts Bank opened, none of the Dorchester spaces held regular hours. Now maybe that points to the audience being hyper local, and thus aware of the scheduling minutiae, but maybe it parallels the cadence of granting cycles whereby the front end is loaded with our hopes and dreams and then our outputs get fuzzier. Have the large, often foundation driven funding models played a role in this?

- What is the relationship between the collective and the individual? Is Rebuild implementing community land trusts to facilitate shared ownership of the Dorchester neighborhood, or is it acting as a (hopefully) benevolent landlord?

I would like to note that while there is value in and of itself for a project raise these questions, I feel we are reaching the end of that being enough. We can do better than settling for art and artists being simply the context for wonky conversations about niche topics amongst small groups of people.

Especially as that small niche group gets smaller and smaller.

You also mentioned a project you are developing called Inside the Beltway which attempts to look past the dominance of the Washington Color School and 1980’s Punk Scene toward the future of the art in DC. Can you talk more about this project?

The Inside the Beltway Project is an oral history project that I am developing to counter those narratives you describe – the ongoing insistence on Color School and punk as domineering narratives. My goal is twofold. One, to aggregate stories that deserve to be told but may have been forgotten or overlooked. This is in an effort to say, “Look! There has been all of this other stuff happening for years,” and to offer up an alternatives to thoughts that DC has been this cultural wasteland for decades.

For example, I used to have my studio in a building that over the years has housed an incredible roster of artists, from Tara Donovan to Kendall Buster to Ledelle Moe to Jefferson Pinder to original occupants Jeff Spaulding and Chip Richardson. Not to mention the institutional histories of the Corcoran, DC public school art teachers and students, Nancy Holt’s site specific project in Arlington… I could go on and on.

The second piece of this is to attempt to use a project as a way to recontextualize what we think of as DC. And I don’t think it is off base or overreaching. The area inside I-495 is approximately the size of Chicago and about 80% as dense as the city of Los Angeles. “Inside the Beltway” is of course a pejorative for life and power here but I think it can be flipped into an actual geographic descriptor of what we mean when we say DC. I don’t think life lived in this area stops at the edge of the diamond. And if we can re-establish these parameters it might be freeing in terms of looking for space, home, life. Perhaps our social histories need to better acknowledge sprawl and the way that people are connecting and working today.

At this point, the project I am working with my co-conspirators at FURTHERMORE is the next step. We are forming a database of stories, scheduling listening and conversation events, and meeting with potential institutional partners to share resources.

It’s interesting that you bring up the parameters of DC. I often find that many artists who identify as being DC artists actually live just over the district line. I feel this happens in similar ways in other cities like NYC and Chicago where the official city limits keep blurring as artists are pushed further out into outlying neighborhoods and boroughs.

What form do you expect this project to take? Do you see this becoming an exhibition, audio tour or being presented as a series of podcasts highlighting the different narratives?

I think that artists who live 500 feet outside of DC ought to self-identify in that way. It more accurately explains the lived experience of this area, you don’t have to go through some portal to cross Eastern Avenue. Nor is it necessary to stage a contest to say that you have to live inside the diamond. Let’s be honest, the strategies by which one can structure one’s life as an artist are multiplicitous, most of which are challenging, and as an audience or peer group I think we are better off if we can frankly acknowledge it. And again, I believe it opens up our understandings a bit.

As far as the dissemination of the oral history project, this is one key point I/we are trying to figure out. My instinct is exhibitions would play a minimal role, but certainly a robust web presence, or maybe vinyl records! Something that is particularly appealing is the opportunity to hybridize the story gathering with the dissemination – for example listening and interview events at public libraries or similar gathering places.

Space has been a big concern in the art scene in DC for the past few years with many artists and groups being pushed out of the area, or over the line into Maryland. Lately in your Facebook feed you’ve been asking provocative questions that look beyond the current models. What other questions do you feel that DC artists aren’t asking?

I think that ultimately what I am after with these posts is an untangling of the different assumptions that art and artists have been operating under – both historically and very recently. For instance you mention space, and where is it possible for art to be made or shown (specifically in cities). In most of the 20th century these activities were able to occur in building stock that other industries were disinclined to want – either in underserviced neighborhoods or under amenitized/non code compliant commercial space. It’s hard to picture SOHO as undesirable now, but the dream of an artist loft was legislatively supported by the city of New York so as to not let those spaces fall fully into disrepair.

Fast forward to the last ten years and you have a complete shift in the demand structure for the spaces that were traditionally available to artists. Now countless industries are seeking large, “cool” industrial space – PR firms, breweries, co-working spaces – all of which can pay orders of magnitude more than just about any artist or artist’s group. And in many cities – DC, Chicago, Miami, Madison – this commercial demand is coupled with population pressures as new residents flock (or re-flock) to cities. So even if the commercial space doesn’t get rented, perhaps it gets bought, rezoned, and made into apartments.

The key thing to acknowledge for me in this trend is that it doesn’t seem to be abiding by the previous understandings of gentrification or development, in regards to artists or small businesses. Take Ivy City in DC for example. Douglas Development was not drawn to that area by the artist enclaves, they were drawn there by the vast amount of space available and the ability for their development to essentially overlay their conception of a neighborhood over vacant space and the existing histories. And then they bring in the “cool” themselves, through some scruffy architecture and their own tenant coffee shops. Plus with the speed by which information moves today, the half lives of all of these changes is incredibly fast.

In the end this is the first assumption I would like to tackle. If the world has changed so much in the last five or ten years why hasn’t our thinking? Fundamentally, city shaping applications alone are so young : Google Maps, Yelp, popular iteration of Loopnet, etc. Yet the conversations around the role of art and artists in cities remains so wedded to traditional narratives of development and the value of artists simply being present.

Now, I do feel that art functions as a social good, but here too the language feels tired. The rhetorical position often seems to be that the presence of art and artists is of some value to communities, but in what way never quite gets answered. Is art of value in the way that firefighters are of value? Or parks? Or water treatment plants? Is it the presentation of art or the making? And if the making, then by experts or by amateurs? Specifically here I am asking about the role of municipal support. Private capital’s embrace or exploitation of art and artists is rather straightforward.

But in terms of public support, I believe that it is time for a much more robust conversation about the structural apparatuses that ought to be put in place. And that is all tied to a conversation about the particular’s of art’s existential value. Are artists the important part of the equation, as a separate type of citizen that provides social value that others don’t? If so, our communities ought to proceed accordingly. Speaking of Theaster Gates, I read that he is now heading a think tank-esque group at U of C to study the ways in which “ethical redevelopment” can be achieved by the incorporation of artists at the grassroots level. This to me says that artists are BETTER THAN other types of citizens for this task. I’m not sure I am convinced, but those are the stakes.

And one last concern tackles an even more recent phenomenon – that of the creative economy. While this term is still new to the vernacular surrounding development, urban planning, and the arts, it already appears to be another way for the conversation to default to creativity = good. But I am pretty worried that the economy part of this phrase rather strongly supersedes the creative part. Not to mention that is allows cities plausible deniability about their support for the arts, able to construct stimulative policies that benefit the hospitality and tech fields under the auspices of creativity.

I think it is time for artists and arts advocates to be pretty antagonistic towards this term, because again I have a sense that the communal benefit provided by arts and artists is quite different than that of thrift stores or distilleries.

I feel there are a lot of ideas and possibly provocations in this interview and I’d like to open up the discussion to readers of Bmore Art. Please comment and open up the conversation further!

Author Paul Shortt is a visual artist, writer and arts administrator. He received his MFA in New Media Art from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his BFA in Painting from the Kansas City Art Institute. He is currently the Registry Coordinator and Program Assistant at Maryland Art Place and lives in Washington, DC.