Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble by Cara Ober

The Walters Art Museum is widely known as a house of rare objects of antiquity, but not a place for contemporary art. When Julia Marciari-Alexander became the Director of The Walters Art Museum in 2013, she stated that she would make it a priority for the institution to exhibit works by contemporary and local artists in addition to the art historical objects collected by the Walters family. True to her word, the new exhibit Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble features the art of our time alongside those of William Henry Rinehart, but takes this union a step further into a collaboration with a local educational institution.

The exhibit came about from an extensive collaboration with MICA, and is one of two paired exhibitions designed to explore Rinehart’s legacy among future generations of artists. The Walters exhibit features research from guest curator and MICA Art History Department Chair Jenny Carson, working in tandem with Walters curator Jo Briggs. As the centerpiece, works by local marble sculptor Sebastian Martorana are featured in the museum alongside those of Rinehart, creating a dialogue about materials, artistic partnerships, and relevance that spans centuries.

“The museum’s founding family was among the great collectors of contemporary art of their time, commissioning works from European and American artists, including some of Baltimore’s own and best, like Rinehart,” says Julia Marciari-Alexander, Director at the Walters Art Museum. “We are fortunate to have an extensive collection of his exquisite sculptures and are proud to highlight them and his exquisite process in this exhibition in partnership with MICA.”

“It is uncommon to have such an in-depth collaboration between a museum and an art school,” explains MICA President Sammy Hoi. “The result is an exceptionally productive interface between academia and curators, between students and professionals, and between the 19th and the 21st century art.”

“The present and future are so much richer when they are informed by the past,” continues Hoi. “At MICA, contemporary artists shape ideas and create works in a historical, cultural and social context. HAND/MADE, which closed March 15 at MICA, was conceived as a contemporary dialogue with The Walters Art Museum’s historical Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble. The two shows share Rinehart’s Sleeping Children as a centerpiece. Hand/Made was an exciting, lively, and witty call and response between history, as represented by Rinehart, and its future, as represented by the contemporary artists.”

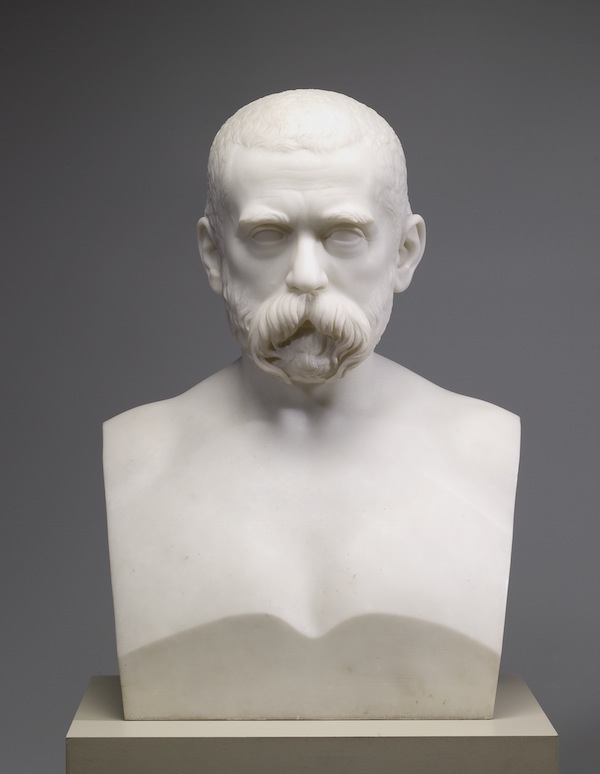

A true local, Rinehart was born in Union Bridge, Maryland in 1825, and studied sculpture in Baltimore at the Baughman and Bevan stone yard and the school that is now known as MICA. Not content to live and work in Baltimore, Rinehart spent the last two decades of his life as a marble sculptor in Rome and became one of the most highly respected international artists of his day. He is widely considered the last important American sculptor to work in a classical style. As his early career progressed in Baltimore, William Walters became a good friend and his most important patron, funding trips to Italy and hosting him in his townhouse on subsequent returns.

Despite achieving a robust success in Italy, the sculptor died suddenly in 1874, leaving behind a great number of unfinished projects and commissions. As was customary, collaborators, co-workers, and partners stepped in to finish them and close up his studio. The documentation of these posthumous partnerships in letters and ledgers illuminated many of the common practices of the day, especially their communal aspects, showing that sculptors produced their output with groups of people, not as lone geniuses, as museum wall text would indicate.

“The goal for the show, which is the goal of my research, is to pull back the curtain on the process of carving sculpture,” explains Carson. “We want to debunk the Pygmalion myth of the lone sculptor slowly chipping away at a block of marble in his studio. We forget how industrial the process of carving sculpture is and was when we see the pristine works in the fine arts museum.” The curator became interested in William Rinehart, for whom the MICA graduate school of sculpture is named, while on a research fellowship at the Corcoran several years ago.

“I think what we are trying to explore with the pairing of the MICA and Walters shows, is the issue of art-making relative to the artist’s hand,” continues Carson. “How important, both then and now, was it that the artist may or may not have been involved with the actual fabrication or carving of the artwork? By Rinehart’s day, there was a lot of tension around this issue, and I would argue that is true today in some cases. So this got me wondering: why do we not discuss issues regarding the artist’s hand when it’s marble?”

Carson set out to find a local marble sculptor, in order to film them working in their studio and create a video demonstration of traditional marble working techniques. MICA’s alumni office pointed her in the direction of Sebastian Martorana, a four-time semifinalist for the Sondheim Prize and a participant in the Smithsonian’s “40 Under 40” Show at the American Art Museum. One of his finished pieces, a marble replica of fuzzy bath towels, is displayed alongside those of Rinehart.

“It was a happy accident that he [Sebastian] got a commission last summer to create a work for which he was using the pointing apparatus [the traditional technique that Rinehart used],” says Carson. “Now the public can see an actual carver at work in his studio using this traditional method. Sebastian has been extremely generous with his time, and he has been instrumental in telling this story of traditional marble carving.”

In addition to illustrating traditional techniques, Martorana’s work illustrates the high level of skill required to produce even a small marble sculpture. Like Rinehart, Mortorana received his training from an apprenticeship at a commercial stone company near his hometown in Virginia.

“Since there really is no formal major or program specifically for stone sculpture in the states, the summer after I returned from Italy I got a job at a stone company near were I grew up,” explains Martorana. “I spent all breaks during my senior year working there and became a fulltime apprentice when I graduated from Syracuse.”

“I wanted to learn how to carve stone like a professional stone carver, not just like a sculptor trying to figure it out,” he continues. “Only years later, when I felt like I had a proficiency in the craft of carving stone, did I return to school to focus on applying the ideas I had to the skills I had been trying to develop.”

Although they borrow Rinehart’s classical techniques to render stone into plump skin, smooth satin pillows, or terry cloth, Martorana’s work employs a post-modernist critique to examine and lampoon popular culture, a stark departure from Rinehart’s serene and idealistic visions. His highly detailed busts of Muppet characters and Super Mario brothers posit the popular characters from his own childhood against the centuries old tradition of civic leaders and war heroes, or “dead white dudes,” as the artist describes them jokingly.

“Why not take the time to memorialize these subjects in the manner that we, as a society, say that we are to memorialize those persons we deem to be of great institutional import?” For Mortorana, popular imaginary figures take on a heightened cultural and moral significance when carved into marble.

In Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble, Martorana’s bath towel sculpture appeals initially because of their Trompe-l’oeil quality: they look just like real bath towels and you wonder what they’re doing hanging on a museum wall. Although it might come off as humorous or ironic, for the artist the piece is a sincere memorial to a family member.

What’s also interesting about Martorana’s bath towel sculptures in the gallery at The Walters is their comparison to Rinehart’s Sleeping Children, which is placed right next to them. In both pieces, marble proves to be a highly effective medium for mimicking the texture and softness of cloth, despite the unyielding hardness of the material. These comparisons – between contemporary and 19th Century, between Classical and Post-Modern – are an invitation for the viewer to understand and appreciate the legacy of Rinehart’s work, as well as the intricacy and skill involved in marble carving, past and present.

Beyond a legacy of exquisitely carved works, Rinehart left behind an estate. Before he died, Rinehart had stated that he wanted his money to benefit artists in the future. As one of three executors of his estate, and as a close friend, William Walters established the first graduate program in sculpture in the US, the Rinehart School of Sculpture at MICA. It seems only fitting that Sebastian Martorana graduated in 2008 with a MFA from this very program.

“Rinehart’s Studio: Rough Stone to Living Marble” runs at the Walters Art Museum, 600 N. Charles St., through Aug. 30. Free. More info at: thewalters.org.

Author Cara Ober is Founding Editor at BmoreArt.