Larry Clark in Amsterdam by Kerr Houston

The March 1962 issue of Harper’s included a real gem of an essay: on page 31, readers encountered the opening paragraphs of Leo Steinberg’s remarkable “Contemporary Art and the Plight of its Public.” In that celebrated article, Steinberg – still a young man then, yet to grow into the famous and controversial art historian – finds himself flummoxed by several works by Jasper Johns, which seem to refuse their viewers even the most basic conventional aesthetic pleasures. Steinberg, though, can’t stop thinking about them, and eventually converts his confusion into a larger observation.

“Contemporary art,” he decided, “is constantly inviting us to applaud the destruction of values which we still cherish, while the positive case, for the sake of which the sacrifices are made, is rarely made clear.” Meaningful new art, in other words, challenges us by denying us our staple diet. It does away with the very things that we think we need in art.

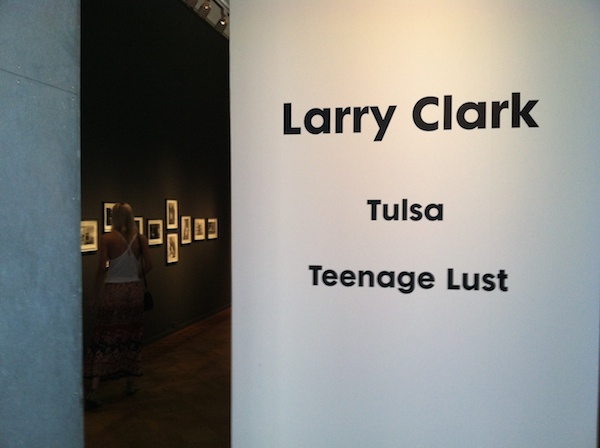

I found myself thinking of Steinberg’s assertion after walking through an exhibition of photographs from Larry Clark’s famous photographic projects, Tulsa and Teenage Lust. Initially published as books, in 1971 and 1983, the two suites of photos currently line the walls of Amsterdam’s FOAM. The images from Tulsa offer candid views of private moments, shoot-ups, and violent altercations in the lives of a number of drug-addicted friends of Clark’s. Teenage Lust, meanwhile, dwells (as the title implies) on the unashamedly priapic interactions of a number of young Oklahomans and on the lives of a number of young male prostitutes who worked the Times Square district in around 1980. Related in spirit to the work of photographers such as Lee Friedlander and Bruce Davidson, the images in both series drew a vigorous reaction in large part because of what they sacrificed, or withheld.

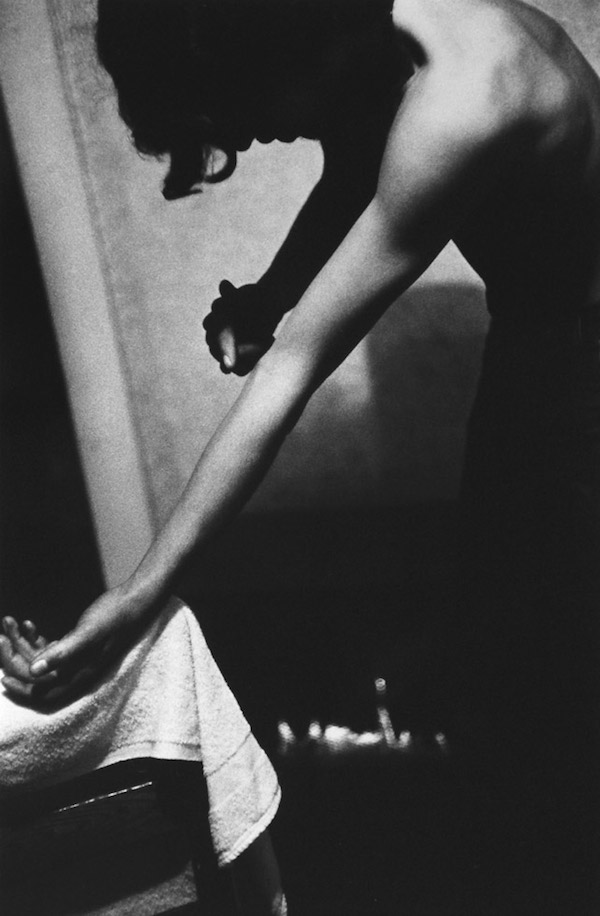

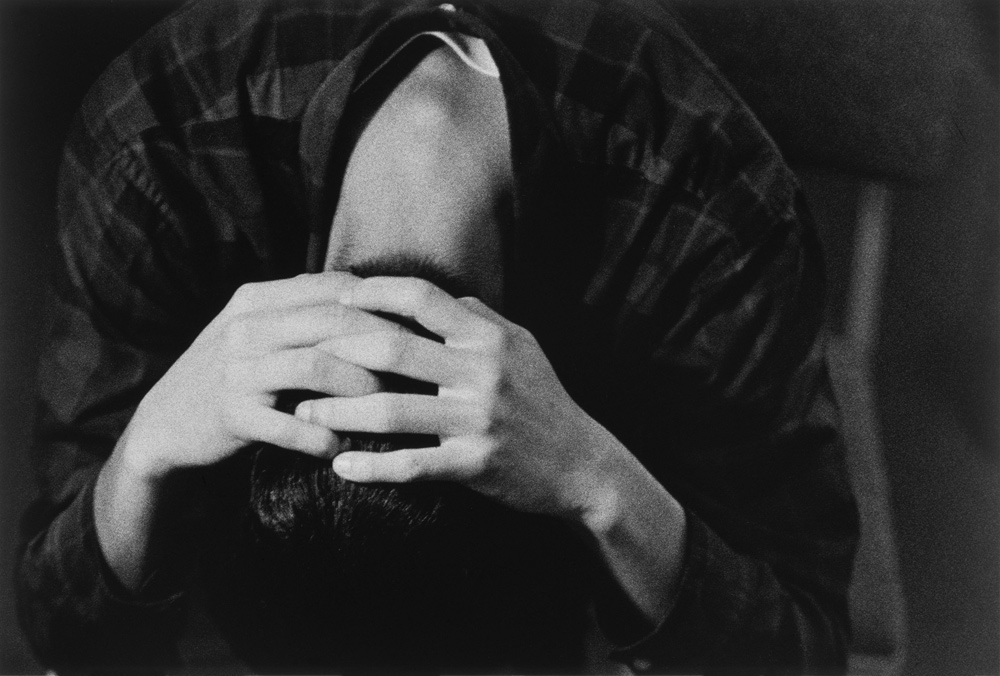

Take, for instance, Clark’s 1971 photo of a young man named Skip, tapping a vein. Like many of the photos in Tulsa, it flatly denied their viewers a comforting sense of objective distance. After all, Clark himself was an addict (which is one reason that it took him more than a decade to complete the second book), and here we sense, in the frank degree of access that we are granted, that he is more friend than photojournalist. Implicitly, then, we are accomplices, rather than innocent eyes. Then, too, there is Clark’s technique, often characterized as raw or coarse. Certainly, the image of Skip is thoughtfully composed. But, as in many of the photographs in the series, the texture is slightly grainy, and figures and forms quaver in and out of focus. (In other images, the camera seems to wobble). Such images were, in Steinberg’s scheme, outrageous; they were violent and brash.

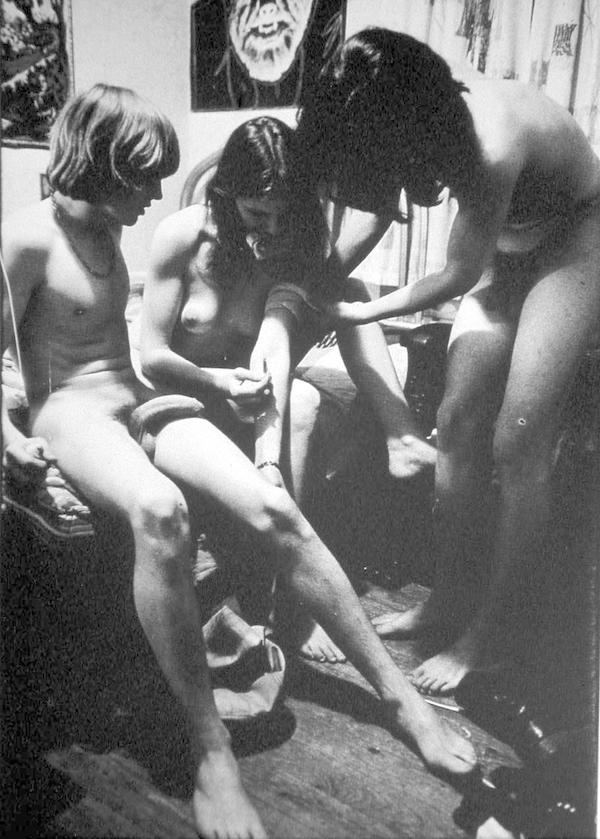

Moreover, some of them destroyed any sense of a larger allegorical import. In another photograph from 1971, three young figures, all naked, huddle around an extended arm, into which the needle plunges. At first glance, the three evince an almost tender sense of collaboration; one thinks of priests gathered attentively about the altar block, or of Renaissance images of the three graces. But then we notice the local details: the injection, the horror movie poster that looms over the scene, and the turgid penis of one of the boys, which sags sluggishly toward the syringe, almost reptilian in its partial wakefulness.

Such details effectively demolish the possibility of an abstract reading: the bodies of these youths may be unblemished and almost insolently displayed, but we are largely denied the chance (granted to us by so much art) to see them as ennobled. Or, as one of Clark’s fellow addicts once told him, “This isn’t a play, Larry. This is real fuckin’ life.” You can gain a sense of the aptness of such a statement if you compare Clark’s photos to Robert Frank’s images of ten years earlier: viewed in such a way, Frank’s record of American life seems clunkily symbolic and actively arranged. By contrast, Tulsa was shockingly direct: in the words of one early review, “this is a collection of photographs that assail, lacerate, devastate.”

That said, Clark’s photographs didn’t merely withhold, or sacrifice. Even as they denied their viewers familiar comforts and aesthetic pleasures, they also gave those same viewers an unprecedentedly frank degree of access: access, that is, to the realities of hard drug usage and teenage sexuality. But here, too, their basic effect might be called devastating. In Tulsa, moments of transitory sociability and apparent tenderness are repeatedly undermined by violence and fallibility. The users jab their fingers at each other, or stare into space, or cringe after a clumsy injection. And Teenage Lust describes an arc of sexual experience that is anything but idealizing: after taking in images of hand jobs in the shower and missionary sex in a forest, we soon encounter the drily titled “Prostitute Gives Teenager his First Blow Job.” In the colophon to that book, Clark claimed that he “wanted to the viewer to feel like you’re there with them – you can be there fucking, smoking dope, having sex…” But to many viewers, this unadulterated degree of access, too, was upsettingly direct. As Mike Kelley put it in a 1992 conversation with Clark, “Tulsa was the first photographic work I ever saw that realistically depicted the drug scene. It shocked me because, at that time, that was not something you saw in the art world.”

And so Clark’s public, as Steinberg might have construed it, faced a considerable plight. Denied its familiar pleasures and forced to contemplate unfamiliar ones, it reacted with initial unease and trepidation – and, in certain circles, excitement.

ii.

In that 1962 essay, though, Steinberg realized that the pain that is sparked by challenging works of art can prove addictive. Indeed, he added, thoughtful viewers rapidly grow accustomed to the baffling gambits of new work – and, embracing such challenges, learn to overcome their confusion with an ever-increasing speed.

“This rapid domestication of the outrageous,” Steinberg suggested, “is the most characteristic feature of our artistic life, and the time lag between the shock received and the caress returned gets progressively shorter.” And, sure enough, Clark’s photos might be said to offer support for such a claim, given their broad influence in photographic circles. As a wall text in the FOAM show notes, his books soon “became a prelude to raw, unpolished photography not based on objective observation by an outsider but instead on the experience of those directly involved.” Works that at first seemed, to one critic, to assail or lacerate were soon converted into a productive template.

But might we approach this from slightly different angles? That is to say, the mounting of the show at Amsterdam’s museum of photography in 2014 prompts several meaningful questions. What, for instance, do Clark’s images mean now, decades after they were initially published? And how does the staging of such a show in Amsterdam affect our response to the images? And, finally, how does their presentation in a series of museum galleries, rather than in the pages of a book, affect our reactions? In short: what is the specific form of the caress returned?

Well, here’s one answer, by means of an anecdote: on the morning after I saw the show at FOAM, I took an early-morning walk along the city’s silent canals – only to stumble upon, at 6:15 a.m., a photographer who was shooting a fully nude female model posed on all fours on the stoop of a Baroque home. I took a few quick glances but, as I passed, averted my eyes: after all, this is a city that celebrates Dutch tolerance and an emphatic sexual libertinism. And so the model’s pose, which might have been shocking if published in 1971, felt almost quaint: just another testimony to the relaxed moral code of a city whose red light district is one of its major draws. In turn, one might say that Clark’s photographs, too, felt comfortably at home in Amsterdam – where, instead of throwing light on a corrupted Middle America or Times Square, they seemed illuminated or sanctioned by northern European permissiveness.

Add to that the fact that it’s now 2014, and that reality television and Jackass are now utterly familiar tropes, and web-based porn a vast and visible industry. It’s not a given, of course, that societies grow more permissive over time – but Clark’s images have surely lost some of their shock value, if only because of their own influence. The blithe affrontery of some of Clark’s subjects, for instance, was extended and amplified by a young Robert Mapplethorpe, whose 1978 self-portrait with bullwhip makes the casual frigging in many of the photos in Teenage Lust seem almost tame. Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumblefish and the films of Gus van Sant have also, through their dependence upon Clark’s work in Tulsa, made that work seem comfortably familiar. Or perhaps you’re indirectly familiar with Clark through Nan Goldin. Regardless, it’s clear: what was initially outrageous can be rapidly domesticated.

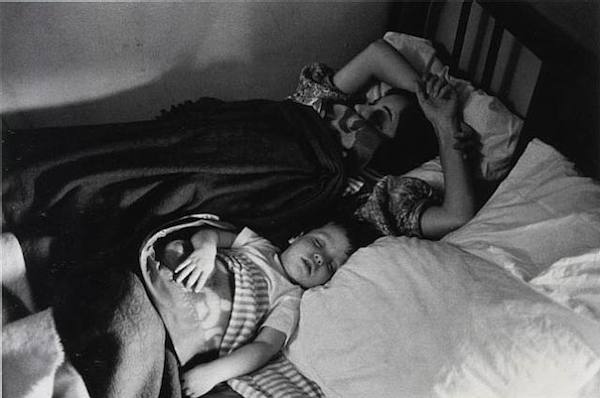

But, still: heroin is heroin, and it’s not for sale in Amsterdam’s celebrated coffee houses. Even in a permissive contemporary environment, in other words, the costs of the drug use documented by Clark seem real. The show’s accompanying materials argue that his work is “completely free of any social agenda,” but I’m not sure I agree. The vacant gazes in the early photographs evoke an almost stranded isolation, which is only reinforced by the fact that the figures pictured in Tulsa never actually look at the camera. One can also spot a sense of detachment in a chilling stretch of a 1968 film by the same name (which was rediscovered in 2010, and screened at FOAM). In one scene, a man fucks a woman (Clark’s protagonists never seem to make love) – and the camera wanders to the thin, jerking legs of the man, which vibrate like flagella in a science documentary.

Meanwhile, other images document domestic abuse (one 1971 photo is titled “Beat-Up Wife”), and two picture infants sharing beds with their addled parents. Such images begin to suggest, in a quiet way, an almost inevitably cyclicality – and thus recall, in their current context, another great Dutch tradition, that of moralizing images of domesticity. Think, for instance, of Jan Steen’s 1668 painting The Merry Family: in it, a debauched family abandons restraint in giving themselves over to pleasure, as children drink from the spout of a pitcher, and scattered utensils dot the floor. “As the old sing,” the caption’s painting reads, “so shall the young twitter.” Or, to quote Clark, “Once the needle goes in, it never comes out.”

In the meantime, moreover, you might say that the cost of that needle has only risen since Clark took his photos. Most of the works on display, after all, were taken before the advent of the AIDS crisis. And so, interestingly, the injections and unfettered sexuality on display in Clark’s work now bear an unforeseeably somber aspect. The scenes of communal banging and unprotected coupling now evoke the spread of a virus that can kill. And those johns who languidly proffer their equipment outside the porno joints on 40th Street? Sure, in one sense they recall a dicier era in New York City’s history, when midtown Broadway was not yet clotted with Cheesecake Factories and Sbarros. But on another plane they are reminders of a moment when there were no tests for HIV, and no need for them.

And, with such historical shifts in mind, we can begin to attend, as well, to the format of the show at FOAM. Clark’s photographs, again, were first published as books – which shaped their effect in certain ways. For one thing, they were arranged in a distinctly linear manner (Clark has spoken about a cinematic effect in his books, thus gently alluding to the idea of a narrative). Hung on a museum’s walls, by contrast, the images can be seen in various orders or combinations, and so any sense of a narrative begins to dissolve, and to yield to a series of diverse possibilities. Furthermore, the museum setting subtly sanctions the images in particular ways: it presents them as fit for public perusal.

By contrast, the books are inevitably more private – and, as a result, more revealing. I recently flipped through Tulsa, for instance, in the waiting room of a local tire shop, and was acutely aware of the possibility that a stranger might see me studying a photograph of a blow job – and judge me for it. Seen on the walls of FOAM, however, the photographs lost that power: they were merely artifacts, hung for the consideration of fans of photography and tourists alike.

In several ways, then, what one gets at FOAM is very different from what Clark’s readers in 1971 or 1983 held in their hands. Okay: but what, in the end, are we left with? That depends, I think, upon the viewer. For these photographs are, despite their raucous subject matters, finally rather like blank screens. We almost inevitably read them in the light of our own fantasies, memories, experiences, and insecurities – and so they are arguably filled not with distinct content as much as they are with associative potential.

Clark argued, remember, that his photographs were meant to allow us to be there, fucking or smoking dope: the works, that is, transport us. At the same time, though, as Steinberg pointed out a year before Clark began Tulsa, much art invites us to applaud the destruction of values which we still cherish. It “projects itself,” he argued, “into a twilight zone where no values are fixed.” And so we who now inhabit that twilight zone are invited to shoot up and to have sex even as we must also consider the ways in which the meaning of those terms and their imaging have evolved over the course of four long decades. The work thus fucks with us even as it invites us to fuck – and as, all along, the fucking landscape keeps shifting.

Larry Clark: Tulsa and Teenage Lust will be on exhibition at FOAM in Amsterdam through September 12, 2014. More info and images here.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.