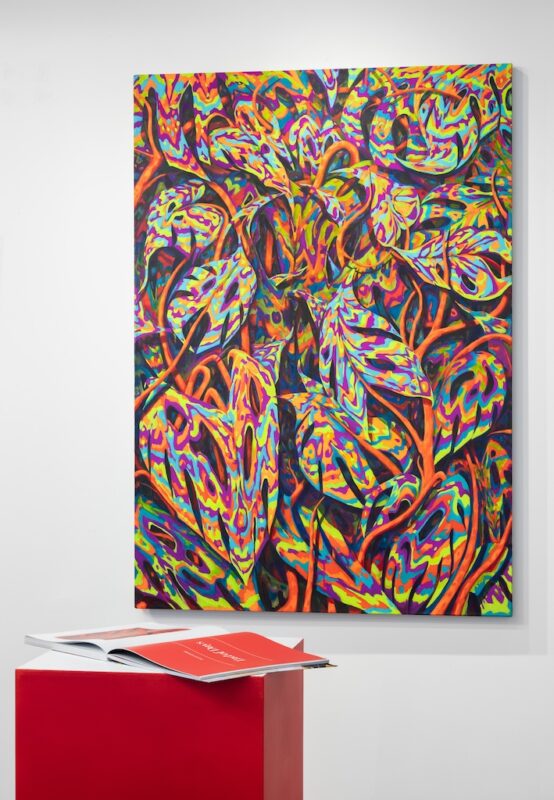

Bret McCabe reviews Front Room: Sterling Ruby at the Baltimore Museum of Art

The problem with a dramatic first impression is not being able to shake it. Case in point: an initial visit to the Front Room Sterling Ruby exhibition at the Baltimore Museum of Art shortly after it opened. The show evoked but a single, solitary emotion: hate. As in, I simply couldn’t stand the works one bit. And, yes, hate is a strong word that should really only be reserved for political and corporate malfeasance, but Ruby’s sculptural fabric fangs looked so profoundly lazy that they produced an equally lazy first response: knee-jerk antagonism.

Now, multiple visits to the galleries later, the impression remains, and it bothers me. Not because I don’t like the work— consider this one vote for the BMA and all museums and galleries presenting things not immediately greeted with open arms. It bugs me because I’m not entirely sure why they provoke such a response yet. I mean, sure: I love Mike Kelley’s use of stuffed animal toys, too. And the floppy shadows of soft sculptures by Claes Oldenburg and Louise Bourgeois are cast over Ruby’s work on view here. So what is it about these that isn’t just boring me, but doing that so inertly?

I mean that sincerely. I’ve had difficulty writing about this show because it’s been difficult figuring out what to say about the installation — ten large, fabric-filled sculptures, either vampire fangs or prone figures that look like dead bodies stuffed into bags — other than to castigate its superficiality. The Front Room pieces are examples of the “soft work” Ruby has been doing the past few years, variations of which traveled through Europe in 2012 and were featured in a solo show at London’s Hauser & Wirth last year. I keep trying to see them as critical explorations of consumer culture and wry commentary on the phallic manliness of monumental minimalism, but these vampire teeth lack bite. And that’s the problem. Clichés spring far too readily to mind when looking at the numbered multiples: the FAO Schwartz holiday-display scale, the Buffy the True Blood Twilight dead horse metaphors that aren’t so much flogged as obliterated through overuse, and I keep circling back to a cul-de-sac of opportunism. These pieces don’t read like critical examinations of global neoliberal consumer culture or the United State’s bloodsucking political hegemony to me. These feel more like the repetitions of somebody who doesn’t worry about paying the rent.

This isn’t my only encounter with Ruby’s output. His 2009 The Masturbator video installation at Foxy Productions produced an odd kind of empathy. For the project he hired male porn actors to masturbate to climax while alone in a room; the process was filmed, and each actor performs this task with varying results. Neither shocking nor transgressive, the installation felt like a study of the ordinary, mechanical anomie of contemporary life’s social solitude, that curious state of doing everything alone but documented in public.

Ruby’s BMA works have yet to present such a thought tangent to pursue, and that’s one of the things that I find most annoying about it. No matter how many times I visit the two galleries it occupies at the BMA, no matter how many times I roll it around the brain, I get no deeper than its superficiality: the vampire clichés, the softness, the patriotic color scheme, the obvious quotation to industrially manufactured objects and commercialism. Looking and thinking about this work does little but send tiny fissures of pseudo-ideas into my skull that end up hissing puns out of my mouth. It’s aesthetic fracking: lots of little fissures leading to one utterance.

Could that be the intention? Using the obvious to draw out the lowest common denominator in the most destructively irresponsible way? I don’t know. I do know I somewhat appreciated the haphazard installation of the one morass of fangs, flag, and body bag. It feels/looks like a store’s stock after it’s been harassed by shoppers all day. That idea makes visual sense to me. I’m just not entirely sure what it’s articulating: That the intersection of our entertainment and our country that powers our commerce is built upon the dead? That’s only an idea that’s been explored about capitalism since the beginning of this whole “democracy” experiment.

I’m not tsk-tsking the work for mining an already existing idea—see also: everything I’ve ever written—I’m merely not sure what Ruby’s bringing to that discussion. What does his work want to tell me about this intersection of death, vampirism, and the U.S. of A? Is the softness of the work supposed to make it more user-friendly, as if by making such potentially scary things look and feel like stuffed animals we might find the whole enterprise more warm and fuzzy? Is this how we win hearts and minds for neoliberalism today? Make it look like prizes hanging up in a carnival midway? Step right up to the ring toss. Winners get a cuddly reminder of America’s global economic blood-sucking to snuggle up with at night.

It’s simply not having that effect on me, which I’m completely willing to attribute to the fact that the more I look at the work the less I like it. The softness of the work and the intensity of the themes don’t feel like that kind of juxtaposition. They merely read as soft thoughts about heavy subjects. They’re status updates: “America is giving me the sads.” Frowny face. And now I’ll click “like” in solidarity before moving on to a video about a baby panda.

Over on Reddit there’s a thread from a few months back offering “advice on how to write vampires without being cliché’d”. Being Reddit, your mileage will vary as far as how helpful this advice is. One commentator, however, emphatically reminds people that vampires are monsters:

“They’re mind rapists who literally feed off the death of their victims and make them like it, to say nothing of turning them into mindless servants themselves.”

Now, there’s a metaphor I can get behind—not because I necessarily agree with it but because it offers an opinion, a feeling, a story. It deigns to take a stand on what it’s talking about.

I realize it’s completely unfair to compare works by other artists working in different media, but because you can hear Camille Henrot’s video “Grosse Fatigue” in the BMA’s Black Box gallery while taking in the Ruby installation, I’m going to anyway. Henrot’s video is a history of the universe, its imagery coming from Henrot’s residency at the Smithsonian Institute Archives, presented as a series of moving images in opening and closing desktop windows, all set to a steady drum pulse and spoke-word performance about, well, the history of everything.

Now, the origin of the world and/or universe is a subject artists have tackled in many ways before. What’s so affecting about Henrot’s take is the element of melancholy she brings to it. The video offers a catalog of the breadth and depth of human knowledge over the natural world, and yet that knowledge feels somehow both incomplete—there’s still so much we don’t know—and in some ways misguided. What we understand has eliminated so much doubt about what we see around us, but it’s also taken away the mystery of the natural world a little bit as well. The spoken-word text, which uses an everyday vocabulary to tell a story of big themes, creates a mythological mood, which the video’s imagery compliments and contrasts. Sometimes the objects in the images are syncopated to the imagery of the text and become echoes of ideas. Sometimes they feel like something plucked from time and space, cataloged, and tucked away into the filing folders of knowledge’s taxonomy. And those spheres don’t always overlap: This is the world we live in, where mythological feelings don’t always jibe with scientific fact, creating an uncertainty in the human who straddles the divide between them.

Ruby’s Front Room works don’t spark the same sort of emotional or intellectual roller coaster in my brain. Maybe that’s because the ideas and genres and eras he’s referencing don’t have the same resonance for me. Maybe it’s because I’m already on board with his ostensible consumerist critique and I want it shouted from every rooftop. Maybe I’m just reading all the wrong things in the work and it went completely over my head. Maybe. But I do also wonder if maybe what’s nagging me about the works is that Ruby doesn’t have anything else to say about the subject himself.

Front Room: Sterling Ruby is up at the BMA through June 15, 2014.

* Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.