Translated by Kerr Houston and Jennifer Watson

A letter to Mr. de Poiresson-Chamarande, Lieutenant General

At the bailiff’s office and presidial bench of Chaumont in Bassigny.

Regarding the paintings shown in the Salon, at the Louvre.

Paris, September 5, 1741.

It is not at all my fault, Sir, if you have lost your patience. I feel greater regret for promising the review too soon than for failing to execute it on time. One can’t make the exposition begin when one wants. I have more enthusiasm than influence, and you must not blame me for that. But, understandably, you might well have complained, seeing as how it is only today that I am able to keep my word.

I did, though, see the pictures the day before yesterday. I promise I did; but I conducted such a cursory review that I was not really in a position to tell you about it. I chose my time poorly. I visited during one of those periods of turbulence when one’s sight is not at ease, and when the spirit, distracted by the whirling eddies of spectators, is incapable of discussing the beauties or the defects of a work. When one feels like this, he can give no more than a quick glance, and a certain distance is necessary for a methodical, judicious review. If we could count on finding only connoisseurs there, we would seek the hour when the room would be especially full: but these are tumultuous packs of all sorts of lookers, who embarrass you or whom you are afraid of annoying because your attention is too concentrated. It’s good to give them some space. And so during my first visit I formed only a confused notion of the different pieces of which I wanted to give you an account. Let’s imagine that I was there only for myself that day, in order (if I dare express myself this way) to sate my desires.

Yesterday I wanted to think about your interests, Sir, and I presented myself at the door, even before the hour at which it was supposed to open. And should the legitimate intention of obliging you ever result in unpleasantness? The guardian of the door, without even bothering to notice if he was insulting titles of nobility, or if I was deserving of respect, without considering me, without looking at me, without noticing me, greeted me with a “No entry” and, ditching all ceremony, turned his back to me and slammed the door.

What to do? He had found the best way of finishing with me. Perhaps someone more tenacious would have wanted to speak through the lock, and by alternating sweetness and anger would have tried to win this inflexible man by negotiation or disturbance.

But not me. He refuses me: I retire and I am left to say, in a tragic-comic tone, I observe with contempt these laughable manners, which make porters into invisible guard-dogs.[1]

And then I thought that this was not at all the only rudeness of this man who had played me that time, and that assuredly he had his orders. So I was trying to console myself as much by that thought as by the notion that I was not the only one who had endured this disgrace. For, instantly, a crowd of fifty people assembled; I left them to murmur about this counter-order and I began to return home.

I hadn’t taken six steps across the plaza when a pompous carriage (which was flying more than it was rolling, due to the dashing speed of the horses that were pulling it), came to a stop before the dreadful door. The luxury of the coach driver and of three valets pretty much told me what I was about to see emerge from the compartment.

First was a young man who was more costume than flesh. It would be better still to call him a richly dressed phantom. The coloring of his diaphanous face was nearly the same tint as the powder that weighed down his hair. His arms and his legs seemed to belong to a skeleton rather than to a living body. He didn’t fail to preen as much as he could. He was a true Count of Tuffiere [a character in a 1732 comedy by Philippe Destouches], pulled from the page, and I think that he lived only through a trick of vanity.

He fell into the arms of one of his men (and it is still not clear if this was due more to weakness or to disposition), while the other squires attended to a woman and a young lady, raised on a diet completely different from that of the little ideal man.

The woman was about forty years old. Her demeanor was conceited, her gaze active, her speech bittersweet – and although she was already very fat she seemed further stuffed with the glory that she drew from the carriage and its crew. The crowd that she found there, awaiting the good humor of the Swiss guard, markedly inflated her love of herself, which seemed to triumph completely when she realized that they had all been forbidden entry and imagined that she would thus be enjoying an exclusive privilege, which would render her respectable to all of those eyes that had been restricted to such a meager meal.

The young lady, who was a happy size and whose appearance was more bright than noble, was scarcely twenty years old. Her gaze might have seemed modest, if she wished, but was in fact shameful. She didn’t open her eyes fully but didn’t see any less for that; it was only by stealth that she looked at you, but it was easy to recognize, in her suspicious reserve, that she was a student of the fat woman – whose hard glances didn’t reveal anything more.

Their vanity, however, was not completely in harmony. In the woman’s eyes, nothing was more flattering than the honor of a privileged entry. The young lady, though, who was counting on a flurry of glances, found this prerogative quite sterile. She didn’t care at all. She would have left it behind in favor of two run-of-the-mill guys whose attentions, rendered insipid to her by their continual staring, were no longer a stew for her little vanity. She honestly feared that her cohort had the courtesy to set them apart from the crowd, and that they might be admitted. She hastened to enjoy a satisfaction that might escape her. She attracted all eyes to her through her vivacity (not to mention the giddiness of her speech and her manners), and she was so caught up in it that whatever came along, she wanted to be certain of having cast sparks into the heart of all who were there.

I won’t speak to you about their complexion. You know quite well that the women of Paris prick themselves in order to have none. Rosewaters, ointments, Spirits of Saturn, rouge: this is everything they take in. Each woman alters these drugs according to her fantasy; how to discern, then, the skin underneath?

The face of the older one was a violent carnation, and one couldn’t have accused her of wanting to fool anyone through the art with which she deployed her rouge. Her two cheeks were more heavily painted than those of masks. I was stunned by the sight of such coloration in the morning.

The younger one hadn’t received the same treatment and, considered alone, seemed in excellent health – but if you looked at her at the same time as the woman, you found in her a weariness, or sort of languor. And, finally, if you looked at her closely, she was plastered only in white.

Anyway, they were both in such a state of undress as immodest as if they had decided to remain at home – but rich enough to rival the attire of much more illustrious ladies.

Now you know them well. It must seem to you that you’re at their side, and you are likely convinced that the Swiss guard who had rejected me as the simple individual that I am (without pomp, without design) wouldn’t hold out against this din. You would naturally have sided with the woman’s presumptuous hopes, and I’ll admit that I at first had the same idea. I was already thinking about gallantly beseeching their protection, and I strove for that of the young lady. Would she want to miss a chance to acquire a courtier? A temporary courtier, to be sure, but, still, one who would have dedicated himself for an hour or two to the honor of paying her homage? Avarice, greed, vanity: they never let anything go. They scrounge, they gather everything, and in the absence of better options they content themselves with small gains. I was thus counting on her.

Their introductor rapped on the door, with the assurance of a man to whom no door is ever closed. But, standing there, he didn’t even get the simple pleasure of finding someone to speak with. In vain, after a long monologue worthy of the character I painted for you, he humiliated himself to the point of entreating, of begging. All was deaf and dumb towards him. He found there an incorruptible integrity.

The ladies didn’t hold their peace: they complained bitterly about the slight consideration that they were being shown. The gaiety that they had brought at a gallop abandoned them all of a sudden, and let the graces that it had sustained melt away. My God, but wounded pride cuts a sorry figure!

There are other emotions that adversity emends. Wounded pride is only the most ridiculous and most unjust. The introductor, who wanted to give this gift himself, ended by taking it himself. The fat woman quarreled gravely with him as they climbed back into their carriage and the horses, less intelligent than those of Hippolytus,

Instead of having a sullen eye and hanging head,

So as to better conform to their sad thoughts [2]

left as nimbly as they had arrived, whisking the humiliated trio away, I don’t know where.

Do not blame me at all, therefore, if I put off until today discussing the agreeable spectacle that I told you about. It was necessary, whether you like it or not. But, finally, you’ll be satisfied: I’m going.

I will follow, as far as I am able, the order that was maintained in the exposition, so that you don’t miss anything in my account: not even the arrangement. I leave you to judge, Sir, if my attention is scrupulous enough for you.

You are first stopped in the middle of the staircase, by two pictures that present themselves on the cornice; they are both like iron firebacks. On one is painted one of those little tables that ladies have at their sides, so that they can set their handiwork down. It is half covered with a piece of needlepoint, tossed there very gracefully. A backgammon board covered with a few cards and dice cups, grouped just beneath with this table, under which it seems to have been pushed slightly. On the other side appears a bowl half full of water. I mean no insult to the rest of the work, which is all excellent, but this porcelain piece is the most perfect part of it.

Art does not know how to make anything more convincing. One feels the wetness and the transparency of the water, as well as the fall of light, which slips into the interior of the basin and produces a certain brilliant gloss – which may be easy to render passably, but which is impossible to imitate to the degree that it is here. The other picture, along the same lines, is not quite so remarkable. It is a cushioned cane chair next to a desk on which a music book stands open, but the effect is interrupted by a violin, which seems peripheral. And on this chair sits a theorbo [a stringed instrument], decorated with a striped ribbon from which the instrument hangs, and which could nicely snare someone. But still some people claim that the violin has no support.

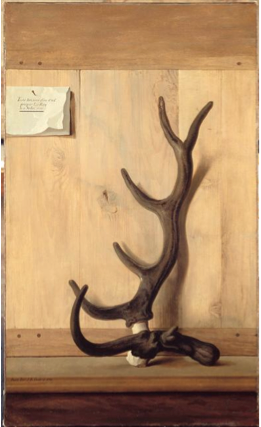

A third very striking piece is the representation of an unusual head of a stag taken by the king, last July 5. I don’t believe that there has ever been, or that there is now, anything better of this sort. You could take the antlers in your hand. They seem to lean against the wooden planks, which are so deceiving that one barely knows how to avoid thinking that the painter has worked on those boards themselves, and even as we know that we are in a salon of paintings, we have to consciously remind ourselves that this is a work of art. And I should tell you that these three works are by Mr. Oudri [Jean-Baptiste Oudry], and deserve, I think, the praise of the whole world. You will pardon me if I cannot itemize everything on display by him. I simply wouldn’t have enough time, or enough words – and I should save some of each for the other works that fill this Salon.

In the same crossing stands the portrait of D[om] Bernard de Montfaucon. To the side is a pyramid of fruit of a rich order and of an unsurpassed truth. It is formed on a silver foot, posed on a marble console. Bottles of wine and wax coffee liquor stand to one side, and on the other a silver coffee pot. Everything is in place in this sideboard, it’s all shipshape, well grouped and quite clear, and it is hardly atypical of Mr. des Portes [Alexandre-François Desportes] – of whom I will have occasion to speak further.

I walk farther, along the wall, past the crossing to the left, and at about the height of the sill I see a picture, representing a manor house farm. The old lord himself and his lady are busy looking at the rustic household, giving orders to a female housekeeper, whose bearing suggests a deep respect for the nobility and zeal for her masters. There is nothing in this work that does not do honor to the intelligence of Mr. [Pierre] l’Enfant, who is its painter.

Its invention is ingenious and its composition very rational. The figures are precisely placed, their characters feel true and carefully differentiated. Next to the principal group, to which I have introduced you, we see a second, made up of a woman who milks a cow, and of a little boy who holds a jar: farther away is a servant who scours the crockery, and who seems to urge a child to take care of some pieces that she has made him carry in the house. On the other side a flock of poultry fills the foreground, and the herds the background; farther back still, a landscape rises in a handsome exhibition, with favorable views.

Everywhere, the light passages are nicely distributed, the local colors neatly mixed together, which gives the clothing the taste it must have. For example, one discerns in the clothes of the noble group a marked, decent economy. We can easily tell that these people wear other clothes in the city, but we also perfectly sense that they are only free in these clothes made for the village. All the rest squares with this, and the subordination is clearly expressed in all of the secondary figures.

One could not lift one’s eyes up from this picture without spotting a historiated portrait representing the Countess de Brac as Aurora. There is a figure reclining gracefully on the clouds, splendidly dressed – or, to put it more accurately, divinely dressed, in a white robe which only partially covers her and is about to reveal a view of her bare neck and legs. Over this robe is lightly cast a piece of blue drapery, in which we can sense a gentle agitation. The way she holds her head is noble, studied, and simultaneously effortless; from her hands, which she has placed favorably, tumble flowers of every kind. Behind her is a small Cupid who bears his attributes. And that little Cupid, who is in a slightly gloomy tone, has implied to some that Mr. [Jean-Marc] Nattier had intended to represent the Vesper (the evening star). But the booklet on sale at the Salon settles the matter: it is Aurora.

In the niche that one then encounters is placed a large pastel, which is a full-length portrait of Mr. President [Gabriel Bernard] de Rieux in his reading room. He sits in a chair of crimson velvet, backed by a screen, and he has to his right a table covered by a blue velvet cloth, enriched by a gold fringe hem. Among the objects that cover the table we see an inimitable snuffbox, turned in the style of [Jeanne-Madeleine] Maubois, and a quill pen that is slightly spotted with ink.

As for the figure, it is such a strong resemblance that it surpasses comment, or even the imagination, and derived from prodigious study. It is highly finished, with the utmost care, and yet an air of freedom disguises the work that went into it. He is clothed in a black magisterial robe and a red cloak. One viewer exclaims, “Look at that peruque wig!,” while another cries, “That cravat!”; the richest are jealous of the Manchester cottons. We feel the lightness of the hair, the fineness of the fabric’s weave and the effort of the worker, the delicacy and the immense detail of the lace. It is a miraculous work, seemingly formed of porcelain: it is not possible that this is only pastel stick. This figure rests on a Turkish carpet, which is no less admirable in its own right. This Mr. [Maurice-Quentin de] la Tour knows the secrets of all the manufactories.

All of the things that the most difficult people criticize in this great piece are merely incidental. The screen looks too much like a fauteuil [an archaic open-armed chair]: it doesn’t make the right impression. A covered table shocks them: they say that a chest with claw feet would provide more room, and they wouldn’t have stacked so many things, one upon another. But in the end, despite these flimsy objections, this painting will always be a masterpiece in its genre, and to give you a sense of its worth, well, they say that the picture’s frame and glass alone cost fifty gold coins.

Another work by the same hand, which represents a Moor from the waist up, does not impress the majority of viewers, but it attracts almost as much admiration from the connoisseurs.

In this same niche, and despite all of the brilliance of the pastel which I just discussed, one sees with pleasure a painting by Mr. [Jean-Baptiste Marie] Pierre, representing a schoolmistress who is giving a lesson to three young girls. This subject is treated properly. The seriousness of the teacher, and the embarrassment and fearful respect of the students: all of this is nicely depicted. Their clothing, though, of simple cloth and few adornments, hardly corresponds to their age and their mood. And I don’t know why these children are all bare-headed. I don’t believe that there is a good reason for this; it goes against custom in a too marked way. For all that, though, this painter (who shows this year for the first time, it seems to me), promises great success.

Moving into the room, we see several reception pictures [i.e., works painted for entry into the Royal Academy] by another artist, named Mr. [Donat] Nonnotte. These are all portraits that convey a deeply truthful aspect. Moreover, the painter’s touch is graceful, the flesh tones convincing and skillfully blended, the local colors well chosen, the attitudes wholly reasonable, the expressions natural. I don’t doubt that Nonnotte will become very fashionable – but, if I may make a further prediction, I believe that he will fare better with men than with women, even if he has shown the ease of l’Epicié [Nicolas Bernard Lépicié] and [Bernard] Du Vigeon in these women.

Intermingled among these portraits is that of the Princess de Rohan, painted by Mr. [Jean-Marc] Nattier, whose brush is easily recognized in the nobility of these heads, in the ease of their attitudes, the choice of flesh tones, the elegance of the garments, and in the grace of the whole. It was, though, less of an honor to paint this portrait than any of those which he had previously undertaken. Nature has endowed the model with so much that art will have difficulty only in not stripping her of any of it in the copy; and whatever one might say about it, it requires much less talent to copy faithfully graces already in existence than to transform some natural sterility into one.

Mr. Tourniere [Robert Tournières] is also showing several portraits, which are striking due to the pleasant tone of their colors; his clothing is tasteful, his drapery truthful, his figures right in place. But perhaps his female subjects should be happier with him than his male sitters: I have a feeling that the work in which he succeeded most fully is the painting of Madame Cousin.

She is very artfully grouped with her son, and it appears that she has just had him read from a book entitled Lessons of Wisdom, on which she rests her left elbow. Her gown is white and interrupted by a drapery of a soft, unbelievably heavenly blue. Her outfit relates wonderfully to that of the young man, who is of a clear and brilliant varnish, enhanced by a scarf of an agreeable, gentle red. The whole yields an accomplished picturesque quality. We breathe, in this painting, an indefinable sweetness and harmony. The only thing one might find lacking is that the eyes of the mother and son are turned outwards, instead of gazing upon one another (since it seems that one is teaching the other).

On the two sides of the door that opens into the apartment, one sees two paintings of a new taste. These are portraits on glass. Mr. [Jacques-François] Courtin, who possesses this talent, which he will undoubtedly perfect in the future, would not be mistaken to stick with it. It is certain that the genre in question is quite effective.

At the end of the side that I am crossing, and way up high, is a large Picture representing Daphnis and Chloe. The scene is in a vineyard at harvest time. The amorous couple makes an inimitable group on a prone barrel, and it is fairly easy to read in the tender expressions of these figures that the story is reaching its end. You can distinctly hear their breaths mingling, you can see their hearts beating. And some small compatriots play near an upturned barrel behind our lovers, watching them and discussing them. On a slightly elevated plane is another young harvester who watches them with an attention even more intense and mixed with spite and with desire. That figure, in her grace, her lightness and her delicateness, is truly what the Italians call svelte. And on a plane far below the subject sits another large figure of a woman that we see from the back. She is drawn quite correctly, her contours and her highlights are perfect, and nothing renders the nude in a more truthful tone. It seems to me that Mr. Jaureat [Étienne Jeaurat] has nothing to seek but a bit more joy in his local colors, which feel too muted.

Lowering your eyes you see three portraits in the style of Mr. [Joseph] Aved, among which that of Madame Croisat makes the strongest impression. She is seated at a tapestry frame; her white satin dress embellished with gold points d’Espagne [needlepoint lace from Spain], as well as her hat with an admirable point d’Angleterre [a bobbin lace of Flemish origin], portray her opulence as well as the eloquent features of her face portray her good soul. This figure’s head is ably turned, her hands are well proportioned, agreeably loose. Her coloring is of a perfect choice. The tapestry, the wool, the thimble, the eyeglasses — which the vanity of any other Woman would have had eliminated from such a picture, and which are by themselves testaments to the reason of this one — all that is of a ravishing naturalness.

Almost immediately after are four views of Paris that occupy the rest of the floor where I am.

The first is taken from the side of the Champs Elysées; the second by the Belleville Road; the third from the Arsenal Pavilion; and the fourth from the Pont Royal. What detail, what clarity! The viewer’s eye is consumed here without getting confused; but how did Mr. [Charles-Leopold] Grevenbroeck’s eye not get confused and lost among all these details that are so fine, so imperceptible? What perspectival depth is needed in order to detail so many buildings! What practice in order to render the paintbrush so bold and the hand so light! One would wish only that his watercolors were more authentic. They have a too-maritime tone. A flowing river, whose current is suggested within the limits of what we can see, has none of that azure impression that the airy plains alone give to the ocean in its immense latitudes and in the abyss of its depths.

Above these masterpieces are some much larger pictures, among which one is struck above all by the one that is exactly at the near end of the casement. It is an example of Indian tapestries, of which all the objects are admirable; but among the others a bay-brown horse stands out, a surprising effect. Mr. Desportes made its main figure. It is necessary to see it for oneself to understand all of its value. The pride of this animal is unmatched in nature – which, without denying it, the painter has ennobled to the extreme.

In the same casement there is an hour of amusement to be had from the production of Mr. [Charles-Nicolas] Cochin the Younger. To the left is the engraving of the fireworks shot at Versailles for Madame [Louise Elizabeth]’s wedding. Nothing more proper than this piece. Nothing more ingenious than all the little figures of the spectators at that party.

Looking down, one is seized with admiration for two drawings in pencil, one representing J. Brutus killing his sons, and the other Virginius killing his daughter. Despite the multitude of figures, which you understand are necessary to represent the Roman people before whom these memorable events happened, there is no confusion at all here. It seems that one could count the spectators and distinguish their movements. One can make out all the heads. But I am crazy, to claim to give you a precise idea of the merit of these two pieces that everyone sees as priceless, exclaiming, What will he do next if he is making such fine things at his age? To which I respond that he will maintain: At the highest degree there is nothing to do but to not decline.

One returns and perceives a nice black and white composition with the title, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture). It is a very clever allegory of the prize that the king accords to that famous society to arouse the students’ emulation. All of its ideas are noble and sublime. Its organization is intelligent and the effect is grand. One sees on the two sides eight or ten small frames, containing small subjects in pencil, in which one recognizes at once the fertility, the accuracy of the spirit, and the exactitude of the hand. One is finally so happy with this examination that one is not at all moved to see whether there is anything above it.

The other doorways are embellished with engravings in which one feels that the burin, jealous of the paintbrush, did everything it could to equal it. But it is only up to you, Sir, to judge in detail the works of this genre. Nothing is so portable, and at the same time so abundant. I am committed to talking to you about only that which is, so to speak, fixed in this room.

I am now at the sculptures across the first crossing. One sees on the floor, in a bronze finish, a globe representing truth in the form of a woman holding an open book in one hand and a quill in the other; her head is turned toward a Louis XV medallion that shows a spirit. Next to her and a bit above, Time rises, lifting a veil. All these figures are of a grand taste. The woman, who is the principal figure, has an infinitely noble way of carrying her head and a refined attitude, without the least appearance of constraint. Time is no less well cast in manner, and moreover, is in beautiful and admirable proportion. In the end this piece would leave nothing to desire, if the medallion had more likeness.

Just beside is a model of a Fall of Icarus. This plaster model is accomplished and designed in an extremely striking manner; the nude has all the fine movements of antiquity, and the drapery is of a lightness worthy of the paintbrush. These two works are by Mr. [Michel-Ange] Slodiz.

Next one has before one’s eyes a group of three women who represent the Baths of Diana by Mr. la Datte [François Ladatte]. He has the talent to situate his figures well, to give them admirable characters, perfect movements, and exact proportions, and to unite them with lots of spirit and propriety. The form of the whole ensemble is of a grand style.

In the other row is displayed a bas-relief of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin which is not sketched, but in which Mr. [Guillaume] Coustou [the Younger] has joined at will the effects of painting and of sculpture. I heard criticism of a wanton air in the Virgin, but as for me, her action seems to me only dignified and majestic, although mixed with goodness and affability. The attentiveness of St. Elizabeth is admirable, and the perplexities of St. Joseph seem expressed in his weariness. The same artist also produced a Vulcan on his anvil, a figure of a grand execution.

In the third crossing, one sees lowered to the ground in the row of sculptures, two large pictures representing two supporting bas-reliefs; one is made in bronze, the other in white marble or alabaster. They are both composed of sets of small satyrs.

It should not be allowed to make the paintbrush so seductive. One does not know what to do to make sure that what one is seeing is only a flat surface. One feels a certain anxiety that the eyes do not know how to calm. For once the mind has received the first impression, that there could very well be a relief there, even if one gets closer, this relief does not at all diminish, and one is ready to reach out and touch it, which would be the only way to resolve this doubt.

These supports are filled with fruit baskets that one does not see without experiencing the sensation that truth could cause. There are peaches, whose velvet almost cajoles the sense of touch by imagination. There are prunes, on which this certain flowery tone, which resembles an impression of dew, feels even better as it is interrupted from time to time by light traces, browner if also shinier, from which the most delicate hand cannot protect that type of fruit. Among all that there are leaves on which the painter marked the assaults of insects. They are bitten, gnawed, torn to shreds. Finally everything is there with such a precision, such a truth, to discourage all others but Mr. Desportes.

On the same row one sees with an infinite pleasure two small models of sculpture in refined plaster. This one represents the metamorphoses of Argus killed by Mercury, whose flute is cleverly cast here. Juno, behind whom lie the body and head of her watchman, identifies in him the eyes with which she will decorate her peacock’s tail. The beauty of this figure is inexpressible. She is so divinely disposed and so regularly proportioned, that antiquity, even the Venus de’ Medici, could not find fault in her. Everything about her is elegant and flattering, everything is pure, delicate, natural and full of spirit.

The Cleopatra represented in the moment when she resolves to swallow a pearl is of no lesser an effect. Her attitude is gallant, and her head is of inimitable character. A Cupid, kneeling, presents her with a cup, which contains the drink [wine, or wine vinegar] in which she will melt this jewel that she just removed from her right ear, and that she considers with an extravagant smile. All of this is miraculous. But I heard criticism of the violence of her attitude, I heard people insist that it was impossible. In addition some found the cup a bit too large; finally, since Cleopatra’s head is leaning to the left, some found another fault in her — that the pearl that decorates the ear on this side looks like it is stuck to her cheek and is not loose. You see very well that these minutiae do not take anything away from the superior talents of Mr. [Nicolas-Sébastien] Adam the Younger.

Placed in the fourth crossing is a small model, in burnished clay, of a full-length statue of the king. The expression of this figure is the most majestic thing one can imagine. It is dressed in the heroic style and crowned with laurels, nobly intertwined. On his two sides, the spirits of arms and of arts are marvelously contrasted. This one, standing, girded with the sword, his head covered with the royal helmet, offers the king olive branches. That one, graciously leaning on T-squares, compasses, and other instruments, raises his hands to the monarch who extends his arm toward him, as if to assure him of his protection.

The pedestal is decorated on one side with trophies, with military attributes, topped with a rooster; and the other side is filled with a bas-relief of all the symbols belonging to the arts, cleverly fitted under an owl that, as well as the rooster, is the bird of Minerva by different accounts. Returning to the figure, it is of the greatest effect that one can imagine; there is a liveliness of composition, whose genius is initially muted.

Here I am, Sir, at that which might interest you even more than all the rest, by the glory that is due to come to the city in which you administer justice. It concerns Mr. [Edmé] Bouchardon, one of your citizens. He has exhibited four bas-reliefs made to be placed under the statues of the spirits of the four seasons, which they typify and which will decorate the superb fountain in the Rue de Grenelle, which will forever bring glory to he who executed it.

These bas-reliefs represent children in the occupations of the various seasons that divide the year. In the first (winter), while one child warms himself with his back turned to the fire, others, lying variously near a dog, look to wrap themselves in a blanket. In the second (spring), some children make floral crowns, which they place on each other’s heads, while another adjusts a garland to a tree. In the third (summer), one of these children works on reaping grain as a rabbit flees; a second tries to trap a butterfly that flutters about the events while a third sleeps on the sheafs. In the last one (autumn), one sees some who chew avidly on the grapes, and others are grouped with a billy goat who has knocked over a basket filled with bunches of grapes.

But there is nothing but this literal sketch. It is everything to see the admirable contours of these little figures, their graceful and naïve movements, their features lost in their fat. Nothing but his rabbit is an effort of Art, and a happy stroke of genius. Next to these works and on the paneling of the door frame are exhibited three more drawings in red chalk, of a great correctness, and which are of a spirit that is easy to produce.

Behind the last bas-reliefs, a bit hidden, is a picture representing Joseph recognized by his brothers. The two principal figures, Joseph and Benjamin, are skillfully lit by the daylight in the back, which gathers on them, and lends them an inexpressible play. This group leaves and comes toward us, and the contrast of the large masses of shadows that fall, though by degrees, on the other brothers, further serves this great brilliance, as well as the bright and dazzling colors that Mr. [Charles-Antoine] Coypel has given to the clothing of those two figures. Finally there are few pictures where the intelligence of the chiaroscuro is more evident. What’s more, Joseph and Benjamin are united with great art, by an embrace that, practiced with spirit in the theatrical taste, shows all of their action – such that one reads, on the two most noble faces in the world, the tender surprise of one and the generous sensibility of the other. One notices their tears ready to escape, and one senses their different reasons for crying. Joseph’s other brothers are properly distributed, and in delightful movements. Everything is alive in this painting, everything here acts in turn, and with contrasts that nonetheless produce a marvelous harmony.

However, some find a bit of mannerism in the faces; but that can be excused here, since these are all brothers, among whom it is natural that one might resemble another. But if one provides that excuse for Mr. Coypel on this occasion, it is no less appropriate in the picture of Athalie, where that resemblance is even more pronounced, between the princess and Abner, who is so close to her that one notices him without the least effort. In that close resemblance, which one finds in other features of the Levites, this subject is executed with a great intelligence.

The figure of Athalie is indisputably a masterpiece, as much for the look of her head, where one reads the darkness of her intents in her covered, fixed, and animated gaze, as for her proud and deceitful attitude, which illustrates at once feigned tranquility and secret anxiety. She is dressed richly in a dress of golden gauze, underneath a tiger fur coat, and that attire that has something somber about it, however magnificent it is, seems to put her heart on display and reveal to us her cruel plans. The scene is moreover filled with other characters, whose silence, attention, fear, and wishes are finely expressed in the body’s action and the face’s features. Abner, who is a few steps behind Athalie’s chair, is of a remarkable truth. His figure, as it is here, performs the entire role that this warrior has in Racine’s beautiful tragedy. In order not to take anything away from the merit of this work, it would be necessary to have a pen equal to the paintbrush that created it. I must however remark that I heard some people criticize in the Joash figure the look of those little wax children: which nearly means that this figure, which is the only one what must speak here, is less living than he is picturesque. But what is that for the price of so many perfections?

This picture, whose examination I regret to leave, gives me occasion to send you, with this letter, a piece of poetry once addressed, on a similar subject, to Mr. A[ntoine] Coypel, father of our artist.

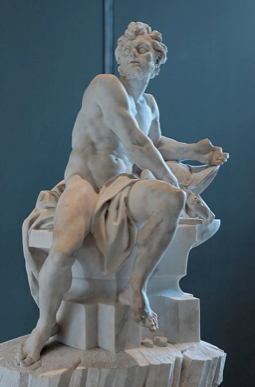

Between the two pictures of Joseph and Athalie that I have dealt with here, one finds four by the hand of Mr. [Carle] Vanlo[o]. The first is a [personification of the Rhône] River, which strikes not only the connoisseurs but also those less specialized in painting. The beautiful figure! Sir, the beautiful figure! It arrests, it shocks, the canvas disappears, there is a man there, extraordinary in truth, but it is a man. One senses the interlocking of the bones, the joining of the limbs, the integration of the muscles and nerves; the connection of the veins, the flesh, the skin, the contours above everything, inimitable highlights; it is a force of the paintbrush, it is a fury of design, worthy of Michelangelo, as profound as him in anatomy, Mr. Vanlo[o] is the best pupil of antiquity.

However, what I just praised, I heard criticized: yes, I heard people who found the bones, the muscles too pronounced. But nothing is as easy to destroy as that frivolous critique, by the comparison of all the watermen to those of other positions; it is certain that they are more nervous, more muscular, more bony. There is thus no harm at all in giving a bit of that element to the figure of a deity, who is only a fictional being, to whom the artist must grant all the power divided among all those who are his subjects.

The pendant of this picture is a river in the form of a woman coming out of the water who rises on her urn. Her attitude cleverly serves as a veil of what must be hidden. This figure is also of a grand effect. One notices the drops of water that glisten on a side of her body, and that one can call the stamp of good taste. One is certain that she is copied from nature, except the face. The model must have been afraid of bad comments.

Between these two subjects one sees a Virgin holding a Baby Jesus. She is of a fairly new and refined taste.

In this same area is one of Mr. [Jean-Baptiste-Siméon] Chardin’s small subjects, in which he painted a mother adjusting her young daughter’s hair. It is always the bourgeoisie that he brings into play. I heard some impertinent debaters gossip about that, and reproach him for falling into mannerism; it is true that there is no more recognizable paintbrush, it is blindingly obvious; but he succeeds in this genre.

There is no woman of the Third Estate who comes here and does not think that it is a reflection of her figure, who does not see in it her domestic lifestyle, her well-rounded manners, her countenance, her daily activities, her morals, the spirit of her children, her furniture, her wardrobe.

And when one knows how to do something successfully, I maintain, it is very laudable to commit oneself to it. Everyone has his measure of talents. This is not the thing to put anyone on trial about.

As for the subject it deals with, one notes a great knowledge of nature first in the figures and their easy and true bodily action, and then in the interior movement. This little girl whose hair the mother prepares, turns away to look in the mirror. In that tilted head one sees her nascent vanity. Her little heart is in her eyes that interrogate the mirror and that eagerly await the little graces that she believes are going to escape her. Plant that figure directly in front of the mother and you lose all that, she doesn’t say another word.

From the place where I currently am, raising my eyes, I see two large pictures.

The first on the left represents Armida and Rinaldo. The figure of the man lying down, asleep on the ground, is grouped with a figure of cupid who, sitting on a shield, protects this hero against the furors of the jealous princess. I do not know how to tell you in a dignified enough manner of the great effect that it [the figure] produces and the impression that it leaves. It is not at all the same as that of Armida. In my view, she has a much less natural expression. She has some kind of stiffness in the arms. And although I admit that her beauty must be extremely distorted by the turmoil that disrupts her soul, it is no less true that it unravels, that in her tranquil state she must be less beautiful than Rinaldo is handsome. Finally this Armida is too small for the size of the picture. Incidentally, one has to admire the prodigious variety of movements and of situations that the painter has distributed to an army of cupids that occupy the foreground, the background, and the middleground of the picture, who walk, climb, and fly at every side. I believe that we would have been satisfied with less. The figures in front are handsome, happy and expressive; and in general this picture will always give the idea of a skilled master.

The next one represents Marc Anthony’s entrance into Ephesus. It is of a grand order and of a composition worthy of the Roman name. One finds all the parts of the painter in this magnificent picture. In it, Mr. [Charles-Joseph] Nattoire shows an exact theory and a graceful practice. But it is above all in his women that he succeeds better than nature. Nature could use his models. He has arranged a troop of these gallantly drawn figures, who are of such a lively action and such delicate features, who are so pleasant, that he leaves us with nothing but the regret of not knowing the women they resemble. His contrasts are admirable, the groups could not be better arranged; everything goes, everything speaks, everything breathes in this picture, so that a flattering color (for the figures as well as for the air), although a bit weak and a bit too even in tones, renders the thing the most pleasant and most joyful in the world.

I am going back downstairs now, and the last objects I am stopping in front of are two portraits. One represents a painter who is holding his colors on his palette, and with the action that he has given himself here, one can judge the facility and the fidelity of his brush. The pendant of this picture is a vestal with the features, some would have it, of the artist’s sister. When you possess the style of this young woman, you can expose yourself without fear in a dress of such character that not everyone would have confidence in. I will be really angry with Mr. Le Sueur if he does not at all humanize himself with other models; his talent would seem to languish.

Now I must give you the lines of verse that I promised you: I have them in original, at least from the hand of the author. It was the late Mr. [Antoine Bauderon] de Senecé, first manservant of the late queen, man known by a number of great works, of which before long I hope to procure for the public an edition, to which I will add his biography: which permits me not to tell you anything more.

I do not believe that these verses have ever been published. I imagine that they have remained in the cabinet of the poet and of the person for whom they were composed. In this supposition I give them to you with all the eagerness of a discovery; receive them with all the pleasure of an anecdote. […]

[1] The author notes, in a footnote, that this is a very loose reworking, of a passage in Act 1, scene iii of Voltaire’s well-known Zaïre.

[2] Portions of the couplet are drawn from Phèdre, a dramatic tragedy written by Jean Racine and first performed in 1677.

** Please note: This is Part 2 in a Series titled “Near the Origins of Art Criticism: An Original Translation of a Review of the 1741 Salon.” To read part 1 click here. To read part 3 click here.

* Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.

* Author Jennifer Watson is a PhD candidate in the history of art at Johns Hopkins University. She specializes in modern art and is currently completing her dissertation on Arman.