Center Stage’s Twelfth Night has a blast finding the low humor in high society by Bret McCabe

If multiple costumes changes add an extra degree of difficulty to a performance, Vanessa Wasche makes it look like more fun than shopping at Barney’s with somebody else’s Coutts & Co. credit card. In her Center Stage debut, Wasche plays Olivia in this lively production of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will, and she spends the entire production gorgeously attired.

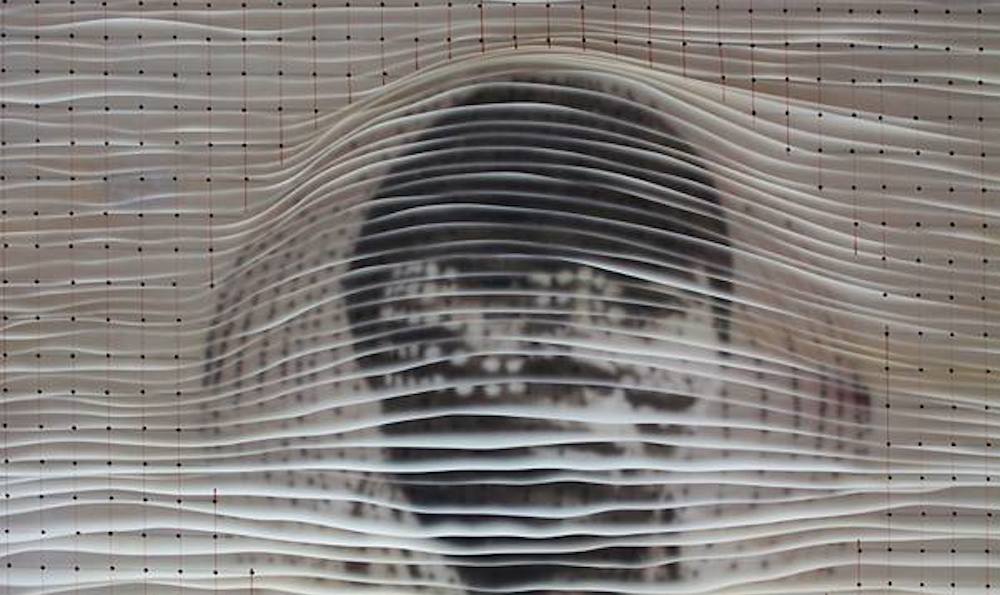

Director Gavin Witt and his artistic team— scenic and lighting designer Josh Epstein, original music and sound designer Palmer Hefferan, dialect director Leigh Wilson Smiley— set this comic romp in a cosmopolitan, urbane realm that feels equal parts 1920s decadent, 1930s topsy-turvy, and early 1940s noir. And costume designer David Burdick outfits Wasche in leading-lady ensembles: she’s first seen in a form-fitting, all-black evening dress that spotlights every curve it covers, and Wasche fills it with a Marlene Dietrichian aplomb, casting aspersions to her entourage and the young envoy who has come to profess Count Orsino’s love for her. Still to come: a series of evening gowns and a white suit paired with heels. Each ensemble looks like it takes an entire staff of lady’s maids to assemble, and every time, Wasche hits the stage without a strand of hair out of place, as if camera-ready for a George Hurrell glamor shot.

The entire production is almost this tightly honed, which speaks to the animating spirit that guides it. By making Illyria, the setting for Shakespeare’s comedy, a hodge-podge of recognizable early 20th century American pop-culture genres, Witt and company situate their romp squarely in screwball comedy territory, where society’s upper crusts engage in the sort of vaudevillian antics that entertained the masses. It’s a clever idea— Twelfth‘s rhymed lines sound surprisingly supple and new when spoken as rapid-fire repartee— and one that brings a number of complex layers to the story. It also turns up the outlandish factor on a number of the already over-the-top laughs.

Twelfth Night is a romantic train wreck of mistaken identity and misdirected emotions. A shipwreck separately strands twins Viola (Caroline Hewitt) and Sebastian (Buddy Haardt) on the shores of Illyria, where each believes the other has perished. Seaman Antonio (Jon Hudson Odom) rescues Sebastian, who spends the majority of the play off-stage, milling about Illyria. Viola decides to pass herself as a young man named Cesario to help Duke Orsino (William Connell) woo the affections of Olivia, who refuses his affections. In the process of singing Orsino’s praises, however, Olivia becomes smitten with the young Cesario, which Viola/Cesario tries to spurn— not only because Orsino has eyes for Olivia, but because Viola is finding herself drawn to Orsino. Meanwhile, Olivia’s uptight steward Malvolio (Allen McCullough) gets tricked into thinking she might have feelings for him, and there’s no risible debasement to which he won’t stoop to please her. When Olivia comes across Sebastian and seduces him into her abode, everything really starts to go sideways.

It’s a familiar tale, but the approach here is so effectively embedded in the interpretation’s DNA that its brio gets the production through some of the slower parts. That’s not always the case: The now defunct Baltimore Shakespeare Festival staged a vaguely 1920s-ish Twelfth Night in 2008, but it felt more like a backdrop. That 2006 She’s the Man film adaptation slapped the play upside the head with The Preppy Handbook during a stretch of teen-centered Shakespeare adaptations. Trevor Nunn’s 1996 film, which set the tale in 19th-century Europe, more effectively integrated its idea into the story, thanks in large part to a stellar cast.

Center Stage’s Twelfth feels as though every detail in its production was made through a screwball-comedy lens. The set can feel like a Manhattan apartment one moment, a plush boudoir the next, and the details— from the deco-inspired radio to musical sounds and instruments that flirt with the schmaltzy lounge exotica that first cropped up in 1930s— subtly reinforcing that era. The cast speaks in distinctly unaccented but vaguely posh American accents, which highlights how Shakespeare is already as tightly written and bawdily comic as an Ernst Lubitsch script. In fact, this Twelfth Night may be Center Stage’s broadest comedy since its 2006 production of the musical The Boys from Syracuse, Rodgers and Hart’s very vaudevillian riff on Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors from 1938.

Why does the 1930s screwball approach retain such a winning appeal? Film writers like to attribute the genre to filmmakers responding to the censorship of the Hays Code and Hollywood offering Depression-era audiences some escapist entertainments. In both instances it’s a comedy rooted in ordinary, everyday oppression. As screenwriter/novelist Andrew Bergman’s noted in his 1971 monograph, We’re in the Money: Depression America and Its Films:

Simply stated, the comic technique of these comedies became a means of unifying what had been splintered and divided. Their “whackiness” cemented social classes and broken marriages; personal relations were smoothed and social discontent quieted. If early thirties comedy was explosive, screwball comedy was implosive: it worked to pull things together.

It’s easier to pull together in fiction than real life, and I’m wondering if part of the genre’s fantastic belly-laughs are rooted in us scoffing at the absurdity of such chasms being overcome. Screwball comedy is where class and sexual tensions can be safely winked-winked away in knowing asides and jokes, and race isn’t that big of a deal because, well, almost everybody is rich and white.

This imaginary realm where everything can come together in the end becomes a creative playground for performers, and Center Stage’s Twelfth Night cast, nine of the eleven making debuts with the company with this production, has a blast mining such absurdity. Connell gamely plays Orsino as a cross between Errol Flynn dashing and Leslie Nielsen deadpan. Linda Kimbrough invests Feste, Olivia’s court jester, with a touch of Groucho Marx’s verbal anarchy. And McCullough’s Malvolio gets to swing from severe fussbudget to a prancing nincompoop in yellow tights.

But having the most fun all evening is the duo of Olivia’s uncle Sir Toby (Brian Reddy) and his mate Sir Andrew (Richard Hollis). Reddy is a veteran TV/film performer and familiar face to anybody who has a soft spot for great character actors, Hollis a British-trained actor now based in New York, and they play Sir Toby and Sir Andrew as impish decadents who don’t have the time nor interest in letting anyone stop their party. Every time they step onstage you get the impression they’re merely passing through during life’s never-ending bacchanal, as if Illyria was somewhere on the trip from an all-nighter at Gatsby’s Long Island estate to meeting up with Nick and Nora Charles for a six-martini lunch. It’s a pair of inspired performances, swerving from threatening to fly-off-the-rails to completely off their rockers, and creating that level of onstage excess is no easy feat. Viola and Orsino and Sebastian and Olivia are this play’s star-crossed leads, but it’s Toby and Andrew you’ll want to meet at the speakeasy after the curtain falls.

Twelfth Night runs through April in Center Stage’s Pearlstone Theater. Get tickets here.

* Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.

** Photos by Richard Anderson, courtesy of Center Stage