Bart O’Reilly Interviews Dublin-based Painter Mark Joyce

I was first introduced to Mark Joyce while I was studying painting in the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) in Dublin. He gave two lectures that had a great impact on my thinking as I was trying to formulate my own ideas about what it may mean to continue to paint. The work he made in 1998 for a show at The Green on Red Gallery has been very influential, and has stuck with me ever since.

I have been fortunate enough to keep in touch with Mark since I have been in Baltimore and have followed the course of his practice over the years. While the questions he asks have changed, there remains a strong interest in paint both as a material in its own right and as a representational tool. He revels in the contradictions and challenges that make painting so difficult. The fact of paint as pigment and its age-old function of representing light in all its facets seem to be fertile territory here. He has agreed to enlighten me over an email/exchange interview. I began by asking him about the work he was making around the time I was studying at NCAD.

Bart: Mark could you talk about the paintings that you made in the 1990’s. If I remember the work in the 1998 “New Paintings” show was a bit of a departure for you. Can you explain how it came about?

Mark: The 1998 “New Paintings” exhibition was very well received in Dublin. It was the culmination of changes in direction due to my postgraduate studies in London and a couple of solid years in the studio. I had been on some residencies such as Bemis in Nebraska also. Looking back I would say it was five years in development, so all of the little breakthrough studio moments were well tempered by then. The positive critical and institutional reception also came at a particular moment in Irish Painting.

Bart: It seems that in Dublin many of the painters of your generation were making work that was often quite related in the terms of theme and content and then in the 1990’s you all went down very different idiosyncratic paths. Is this even accurate? This was my perception as a student.

Mark: There had been a frustration with the dominant Irish Neo-Expressionist painting that had prevailed right through the 1980’s and 90’s. My generation was trying to stay clear of all of that overwrought rhetoric. The amount of exhibitions with screaming purple heads I had seen, it was total horseshit. I would have been saying this to students at the time, to be more analytical, personal even, and not to go for this “one size fits all” angst.

I suppose this takes you away from the human figure and “figuration” towards more formal concerns. I am thinking of Irish painters my own age like Ronnie Hughes, Sarah Durcan, Fergus Feehily, Maureen O Connor, Alison Pilkington, Mark O Kelly, and Patrick Michael Fitzgerald in Bilbao.

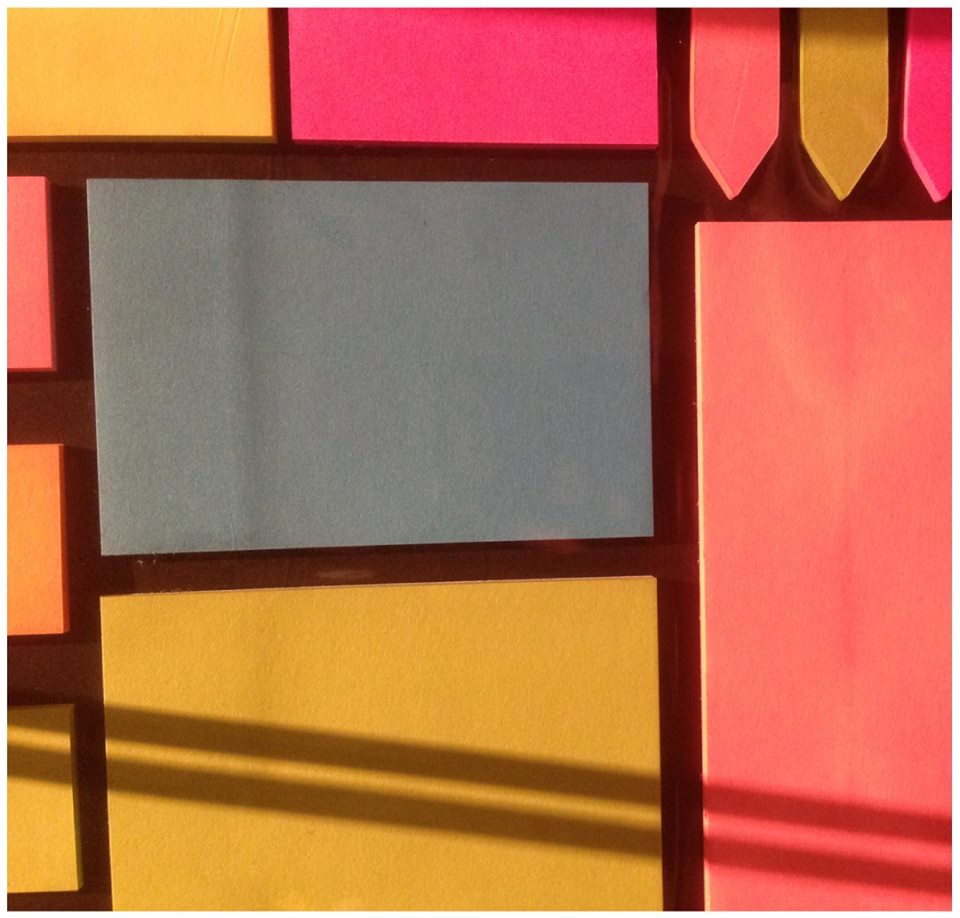

Bart: There are two works that you made that I would like to hear more about. The piece that you made for the M50 in Dublin that I have driven by many times when I have been home in Ireland, and the work that you did at the Albers Foundation in Connecticut. They seem to add a spatial concern into the mix and I was wondering if that was a conscious decision.

Mark: I have always been a bit skeptical about the stretched canvas rectangle as the only site for all of my creative work. I remember the automotive and industrial designers at the Royal College being surprised that anyone could limit themselves to spreading paint onto small surfaces. When you work with colour in the outdoors, there is a massive challenge, it’s not just a question of scale, but that’s a big part of it. The aim was to try to get people to see colour again, to interrupt the everyday with pure physical colour. What happens when you and your body come across colour for its own sake in the natural environment, and what if there is a particular sequence? It’s very different to the gallery. Every time I pass the work on the M50, I regret that it is not three times bigger; you need a kind of Soviet scale.

Bart: Colour also seems a constant but you seem to be treating it very differently in recent works could you talk a bit more about that?

Mark: After the 1998 exhibition, I became bored with the thing I could do in the studio. I was looking at a lot of photography and it seemed to have more veracity, to be more honest than painting. I got a medium format camera and was amazed at the Vermeer-like scene in the Fresnel Glass. So I had a couple of shows, mostly simple shots of roadside Irish “Vernacular Architecture” and DIY buildings, of which there is a lot. I was interested in the light coming into the body of the camera. I kind of lost the audience for my earlier work, and when I came out the other side I was into a very basic type of painting, which on a bad day can look like a beach towel. (It’s heartening for me to see Mary Heilmann can do in this regard.)

The past decades work had at its heart a concern for the anomalies of working with chemical pigments on a two-dimensional surface, in the pursuit of intangible three-dimensional physical light. At this stage I am a sort of amateur expert on all things Newtonian. I am happy pulling colours across the paintings in the studio, trying new motifs and looking at the interactions.

Bart: There seems to be a real gap between how artists are trained in art schools and then what is expected of them once they become “professionals.” I say this because I understand why you moved quickly from the 1998 ‘New Paintings’ show to photography, then back to painting that deals with the representation of light with pigments. It all seems like a natural progression to a trained artist, but as far as galleries and showing work every few years goes these seem like massive leaps and changes. People kind of want things to look a bit like the last body of work.

Mark: I was lucky enough to do a five year undergraduate program over a six year period and then on top of that a two year MA. That’s a lot of studio time! The same undergraduate BA is just three years from start to finish now. You and I know that it takes about six years studio time to paint what you want, how you want, when you want. Young painters will make quite poor work, with lots of inconsistent development and some very thin concepts behind it; let’s call it “emergent.”

Hopefully you get all of this done in college and emerge into the industry with a complete voice that suits you. Even then there are usually a few contrary ingredients in any artistic practice, which may or may not cohere and need to be expressed. I had a strong view that paintings should be seen with other types of artwork, and that you also might need to work things out in other materials from time to time. That said, my approach to making anything would be on the shoulders of all of that painting studio experience. For instance, I think I can see the “painter” in your time-based works.

Bart: You mentioned Mary Heilmann and she is a painter who I have followed a bit, too. I really enjoy the way that she paints and her use of color. It seems at least here in the States that painting, particularly colourful abstract painting, is often dismissed by critics as a decorative easy sell to the 1% at art fairs. Is this true in Ireland also?

Mark: There is a very small art market here and it is focused on Irish 19th and 20th Century oil paintings. It is very conservative and has no connection with anything international. As a contemporary painter, there are frustrating moments when you are placed within this uncritical market context by arts administrators and curators. The emergence of the International Art Fairs was a positive thing for us, it side-stepped the existing critical institutional “Gatekeepers” mostly in London and blew things wide open. It is completely global and as such, all art forms are at the table, good and bad. The different discourses gather around their own values and interests. For my part it is great to see Bridget Riley, Mary Heilmann and Amy Sillman working at the highest levels at this time.

* Author Bart O’Reilly is a multi-media artist and adjunct professor at Harford Community College. He has shown work in Ireland and the United States and writes about art and critical theory.

Featured Image at top: Mark Joyce. Color Installation Albers Foundation, CT USA 2007. All images courtesy of the artist.