Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950 by Kerr Houston

Let’s begin by flashing back, briefly, to 1922, to consider two distinct moments. In Japan, as interest in amateur photography is surging, a new monthly appears on the shelves of newsstands. Titled Art Photography Studies, it is a fine arts journal, but its editor-in-chief, Minami Minoru, wants to foster a democratic spirit, as well. “Art,” he writes, “is creation,” and his meaning is clear: anyone holding a Kodak Vest Pocket can, in theory, could create. Meanwhile, thousands of miles to the west, the Dadaist Tristan Tzara delivers a lecture in Paris, in which he offers his audience some clear advice: “Always destroy what you have in you.” Indeed, he contends, destruction is at the very heart of his own aesthetic philosophy: “As Dada marches,” Tzara explains, “it continuously destroys, not in extension but in itself.”

So, then: in the relatively immediate aftermath of World War I, were artists to create, or to destroy? Was their brief to forge, as Alberto Giacometti would argue, new realities – or were they to follow the lead of Filippo Marinetti’s Futurists and to “destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind”? To build something new, or to tear down the old? Or was such a dichotomy, perhaps, actually an illusory one? In the 1840s, after all, Mikhail Bakunin had famously claimed that “the urge to destroy is also a creative urge.” Picasso, in turn, saw his artistic practice in similar terms, asserting that “In my case a picture is a sum of destructions. I do a picture – then I destroy it.” Creation and destruction, from such a perspective, are thus integrally related activities: irreducibly twinned actions.

But that, of course, is merely a truism. Might we be more specific? Damage Control, a show now on view at the Hirshhorn (through May; it will eventually travel to Luxembourg and Austria, as well), offers an engaging display of a number of the ways in which artists have drawn on the theme of destruction. Notably, it limits itself – and more on this later – to fine art made since 1950. And, in some ways, it is a slightly uneasy marriage of distinct approaches: the show apparently took shape when Kerry Brougher, who was researching the relationship between contemporary art in the 1950s and Atomic Age fears of global annihilation, joined forces with Russell Ferguson, who was mulling over the possibility of a show on destruction as a creative impulse in contemporary art. The addition of Dario Gamboni, who has written at length on modern examples of iconoclasm, as contributing writer for the catalogue complicated things further. But the result, nevertheless, is rich and potent, and it offers a supple and relevant way of thinking a range of related subjects.

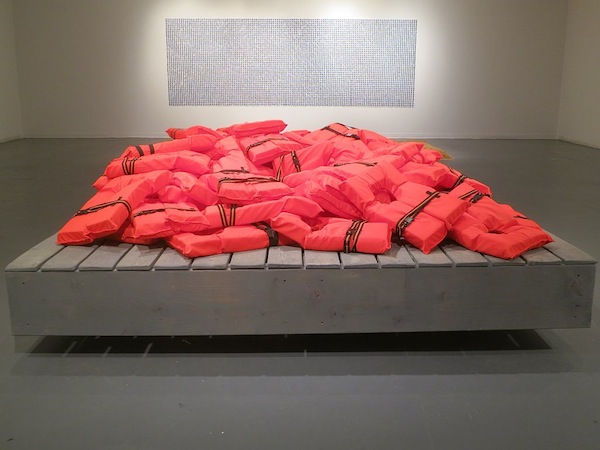

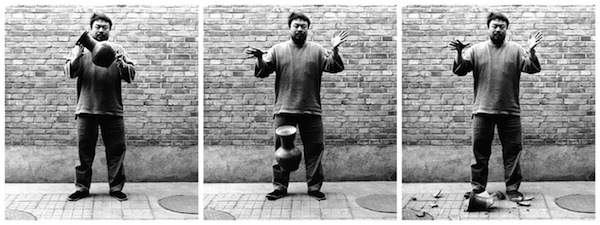

Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

The show occupies the familiar second-story ring of the Hirshhorn, and a real part of the pleasure in strolling through it lies in trying to anticipate the contents of the next room. Will Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing be included? Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn? Yes, and yes – but as we look at these familiar pieces in combination, we come to see that they are more than mere brashly Oedipal gestures of defiance.

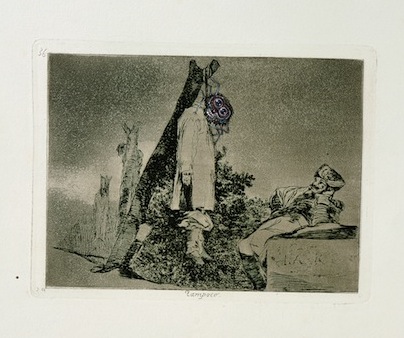

They are also nuanced reactions to local conditions: attempts to clear room for new ideas in the virile bars of Tenth Street, or to protest the stifling and destructive bureaucracy of Beijing. And other examples of the willful mutilation of extant works of art quickly compound this sense of variety. John Baldessari’s 1970 Cremation Project documents the incineration of a number of his own paintings and the conversion of a portion of the resulting ashes into wafer-like cookies: the result, imbued with heavy religious overtones, is simultaneously somber, arch, and liberating. By contrast, the Chapman Brothers’ Injury to Insult to Injury, which involved the controversial addition of dozens of ghoulish, cartoonish details to a series of celebrated etchings by Goya, reads as a dark rhetorical question involving the theme of artistic destruction. “After all,” Jake Chapman has asked, “how far do the commissioners of avant-garde iconoclasm wish their clowns to go?”

Chapman Brothers’ Injury to Insult to Injury

Chapman Brothers’ Injury to Insult to Injury

That’s a fair question, and Damage Control provides a detailed context in which we can begin to draft an answer. Clearly, artists since 1950 have repeatedly mined the possibilities inherent in the destruction of earlier works of art. But they have also explored the central motif of destruction in other senses, in modes that range from sensationalizing to elegiac. Many of the works in the show are centrally concerned with the documentation of visible destruction. Andy Warhol’s 5 Deaths, for instance, involves the serial reproduction of a photograph of a grisly automobile wreck; his saturated re-presentations of the image act as a commentary on the commercial appropriation of death, even as they also recast America’s mid-century romance with the auto as a dance with death.

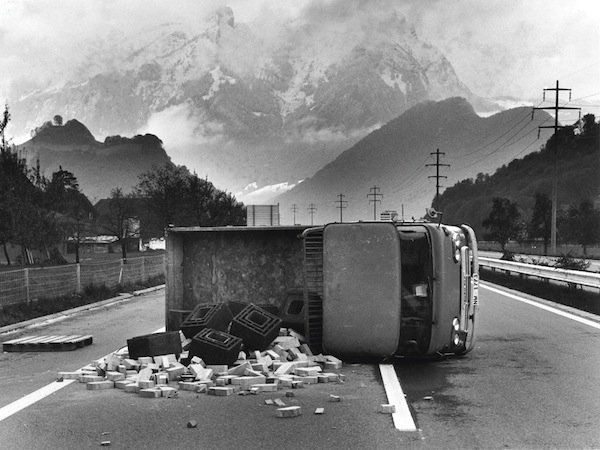

By contrast, Arnold Odermatt’s quietly understated photographs of the residues of auto accidents in Switzerland kindle a quiet and touching sense of human frailty and insignificance. In the 1973 photo Stans, for instance, a truck lies on its side, a puddle of seeping leaked fluids evoking blood and a spilled jumble of cinder blocks cascading towards us. The scene feels tragic on one level, but trivial on another: there is no corpse visible, for one thing, and when we notice the vast Alpine peak rising up beyond the truck, we realize that the force of a skidding truck is nothing compared to the seismic upheaval required to bring a mountain into being. And then we sense, again, that destruction is so often also creative: mountains emerge from a ring of fire, and the screeching brakes of the truck give way to the quiet click of the shutter of Odematt’s camera.

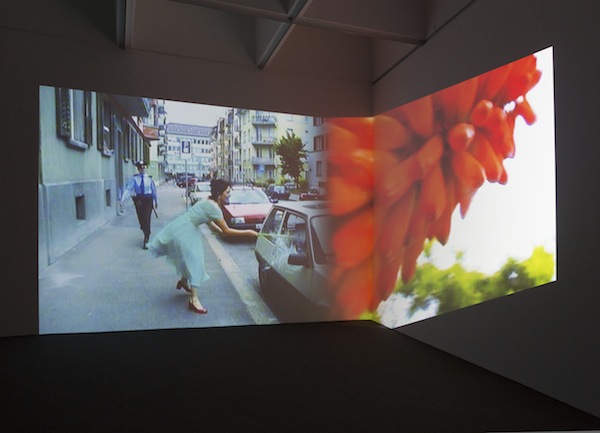

Ever Is Over All, 1997, audio video installation by Pipilotti Rist

Ever Is Over All, 1997, audio video installation by Pipilotti Rist

Some of the most provocative pieces in the show, though, go beyond merely describing acts of violence, and instead effect them. Ed Ruscha hurls a Royal typewriter out of a speeding car, and then documents the resulting trajectory and damage in a wryly clinical manner that recalls a police report. Pipilotti Rist, in her 1997 video Ever is Over All, buoyantly strolls along a city sidewalk in a summer dress, occasionally pausing to shatter (with a large artificial flower) the windows of adjacent parked cars. And, as we consider such examples, a sort of vocabulary of destruction emerges. When Raphael Montañez Ortiz attacks a piano with an ax, we understand that he is assaulting, among other things, cultured tradition; when Christian Marclay drags an amplified electric guitar behind him as he drives on country roads, he is quietly drawing on a half-century of Dionysian rebellion even as he is also evoking the brutal 1998 lynching of James Byrd, whose body was pulled in the dust of a pickup truck. The object under attack matters, in other words, and it’s thus perhaps significant that several of the artists destroy vehicles and houses: purported shelters, that is, for our own vulnerable frames and ambitions.

But if certain general subjects recur, the specifics also matter intensely. Gordon Matta-Clark’s use of an air rifle to shatter the windows of the art gallery in which he was showing photos of broken panes of glass in the impoverished South Bronx acquired much of its force from the distinction in contexts. The gallery windows were replaced, apparently, almost immediately – an option hardly available to the destitute residents of the Bronx. Destroying one window, then, is not necessarily the same as destroying another.

Similarly, Thomas Demand’s photograph of a restaging of the aftermath of an accident in the Fitzwilliam Museum (where an unfortunate visitor fell while tying a shoelace and bumped into three valuable Qing Dynasty vases, shattering them) derives much of its force from the fact that Demand was trying, like the shocked conservators at the Fitzwilliam, to reassemble an absent whole. Damage control, indeed: his photograph alludes to an attempt to contain disaster, while also using that very misfortune as a point of creative departure.

For the most part, the curators are content to let the works speak primarily for themselves. A few of the more conceptual pieces are accompanied by explanatory texts, and the juxtapositions of certain pieces clearly foreground particular shared aspects – but most of the works are allowed to operate, more or less, on their own terms. It’s a satisfyingly productive strategy: viewed in relation to Harold Edgerton’s Kodachrome films of detonating atomic bombs, for instance, Yoko Ono’s quiet Cut Piece, in which viewers were invited to shear a piece of her clothing using a provided scissors, can be seen as a restrained but ardent commentary on the violence done to the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (a point that was developed explicitly ten years ago by Julia Bryan-Wilson but that is simply implicit here, via the quiet juxtaposition).

That said, though, the exhibition clearly has a point of view. It is clear, for instance, in the introductory wall text, which argues that “while destruction as a theme can be traced throughout art history, from the early atomic age it has become a pervasive element.” That position is then reiterated in the handsome catalog, in which Brougher claims that in the years after 1950 “artists embraced destruction in more profound ways than ever before.”

Well, maybe – but, then again, maybe not. Certainly, it’s true that a number of artists active in the 1950s and 1960s thought openly about the place of the fine arts in the era of the A-bomb, and Brougher’s catalog essay offers a good deal of relevant context as it surveys the visual culture of mid-century America. At the same time, though, his essay’s wise acknowledgement of the relevance of additional figures as diverse as Godzilla and Slim Pickens points to the rather arbitrary boundaries of this show. Mid-century nervousness about destruction, and creative responses to that nervousness, were hardly limited to the fine arts – so why limit the exhibition so stringently? Or, for that matter, why insist upon a heightening of profundity in the years after 1950?

Even a cursory glance at the range of visual and verbal responses to World War I shows that that bloody conflict, too, sparked thoughtful and potent responses. The terms changed, to be sure, after Hiroshima, but to insist that an attention to destruction somehow became more pervasive and meaningful after 1950 is to dismiss, cavalierly, the accomplishments of artists as diverse as Otto Dix and Man Ray. But why, really, stop at 1918? For my money, the juxtaposition of the crucified Christ and two iconoclasts whitewashing a mosaic image of Jesus in the 9th-century Khludov Psalter is as pointed and heartfelt as any of the works on exhibit in Washington. Clearly, artists have long been interested in destruction, and pretending otherwise only obscures the way in which destruction and creation are inextricably and inevitably related.

Furthermore, it’s also worth noting that the selection of themes on display, while affecting, does involve some intriguing omissions. I thought, for example, of Superflex’s Flooded McDonald’s, a 2008 video that depicts the slow submersion of a replica of a fast food interior (and which was once screened at the Hirshhorn). That work offers a moving study of surfeit and excess even as it also gestures towards the Judeo-Christian notion of cleansing through inundation, and thus could have enriched the show, on a theoretical level.

Even more striking, though, was a nearly total absence of work related to nature. Two paintings by Monica Bonvicini do refer to the wake of hurricanes, but in a glancing, studied manner. How might the inclusion of video footage of Katrina, shot by one of the residents of the Lower Ninth Ward, have altered the show? Or, say, the addition of Antti Laitinen’s Forest Square, which documents his careful sorting of a 10-by-10-meter square of felled forest? And then, too, it’s hard to overlook the fact that little of the work in Damage Control meditates on the many forms of destruction that can befall the human body.

Sure, Warhol’s work pictures the victims of a car crash, and Chris Burden makes a brief appearance. But there is not a single explicit reference to the AIDS crisis, and Ono’s Blood Piece (“Use your blood to paint. Keep painting until you faint. (a) Keep painting until you die. (b)”) is of course a mere proposal that was never meant to be enacted. Destruction, in this show, is largely object-based, rather than environmental, and usually mediated, or hypothetical, or contrived: in a word, it’s selective.

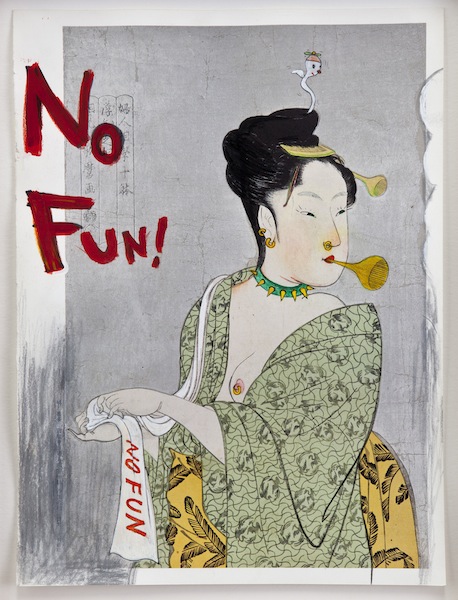

Yoshitomo Nara No Fun! (in the floating world)

Yoshitomo Nara No Fun! (in the floating world)

And it’s also emphatically Western in origin. Ono, of course, is a major exception; so, too, are the altered reproductions of ukiyo-e prints by Yoshitomo Nara. But Ono’s practice, even given that it is influenced by Fluxus, is so distinct in outlook that it points to certain assumptions shared by the rest of the work on display. In a September 1966 talk cited by Brougher, for example, Ono insinuated that destruction may in fact be impossible, given that we always retain an image of the absent object, and then went on to point to the example of a Japanese monk who burnt a beloved temple precisely so that he would never have to witness its deterioration.

Such an anecdote reminds us, in turn, that the topic of affirmative destruction is one with a considerable history in Buddhist Asia. The 10th-century Chinese Zen master Suibi, for instance, once reacted to reports of an adept’s burning of an image of the Buddha with a proud rejoinder. “Let him burn the Buddha if he wants to,” Suibi proclaimed, anticipating Ono’s position, “but he can never burn the Buddha to ashes.” And Dahui Zonggao, a 12th-century Chinese Zen master, reportedly torched the woodblocks of the Blue Cliff Record precisely because that text had begun to lead to the ossification of meditative practice.

Admittedly, such anecdotes can feel archaic, or remote – until, that is, we realize that the tradition of public self-immolation is in fact still occasionally practiced by Buddhist monks who are particularly distraught by current political or religious conditions. It would be a stretch, perhaps, to call such acts artistic, but they are bound up with a tradition of creative destruction that ultimately dwarfs – like the mountain looming in the background of Odermatt’s photo – some of the merely abstract entries in Damage Control.

But no show, of course, can do everything. And, certainly, Damage Control manages to do something memorable: to give a precise form to the common maxim (made by Ralph Ellison and Keri Smith, among others) that “to create is also to destroy.” Moreover, this is a relatively timely exhibition: a week after it opened, a painting purchased in a thrift store and altered by Banksy (who added an image of a seated Nazi military figure to the verdant landscape, in a gesture reminiscent of the work of the Chapman Brothers) sold at auction for $615,000. Creative destruction, clearly, sells.

Finally, the topic of the show is also meaningful in a local sense. Given the recent difficulties that have plagued the Hirshhorn, the theme of the show is especially provocative. Impressively, though, the organizers seem to embrace such a potential irony: the last works in the exhibition are two 1990 drawings by David Ireland that depict proposals for rings and troughs of fire on the exterior of the Hirshhorn. The fire, in the light of the museum’s difficult summer, feels almost metaphorical. But it is also, in the context of this show, almost defiantly celebratory. Yes, flames encircle the Hirshhorn. But as a result, it burns all the brighter.

……………………….

Damage Control will be on exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum through May 26, 2014.

*Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.