Terence Hannum is a relatively new artist in Baltimore, but he is already making an impression with a unique brand of mixed media work. After a solo exhibit at Stevenson University this fall, Hannum exhibited a number of collages and drawings at Nudashank and sophiajacob. Before moving here, he showed work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Allegra La Viola in NYC, and Locatie Z, in The Hague, Netherlands, among others. Beyond his visual art career, Hannum plays in heavy metal bands, touring off and on for many years. Rather than keeping the two practices separate, the artist has fused them into an uneasy marriage that presents a distinct, dark, and wildly theatrical aesthetic.

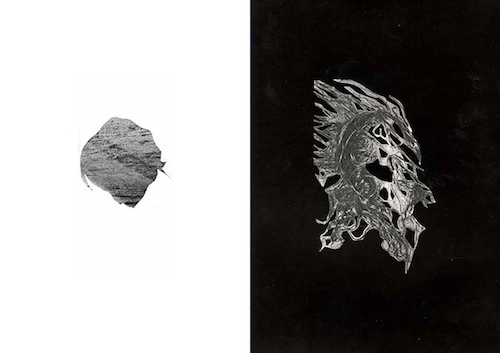

In a new direction, Hannum has combined three years of drawings, collages, and texts into a book, titled AYPS, which will be available this March. The book is published by Kiddiepunk, and also includes an interview with author Kevin Killian. Hannum agreed to an interview with Bmoreart to discuss his work, opinions on hair bands, and to talk about his new book.

Bmoreart: I read that you moved to Baltimore from Chicago to teach at Stevenson University. Is this true? If so, when did you move to Baltimore and what do you teach?

Terence: I did, I had gone to Chicago for graduate school at the School of the Art Institute and I stuck around teaching and making art and music. It was a great city but I needed to get onto the east coast, and I needed to be able to work full time. So, I moved here in 2011 to teach Foundations at Stevenson University, where I coordinate the Foundations program. So basically the introductory courses like Fundamentals of Design and Drawing.

Bmoreart: Suddenly, it seems that heavy metal head-banging is in vogue. You’ve been making work about this type of transcendent musical experience for many years. How do you feel about the sudden ‘hipness’ of metal culture?

Terence: I approach it with amusement. You know our culture is very porous now, within a few clicks you can go from the esoteric black metal from brazil to recovered b-sides of obscure Cleveland soul. I mean I think it cycles through. Obviously it is good for some bands who’ve been working for so long and not getting the recognition they deserve; like maybe this band Absu from Texas. Just a great metal band but they’ve been in Pitchfork a few times the last few years and are one of the first black metal bands in the US. So it does have benefits for a band like that to get deserved attention. Though it also has like certain detriments, that subcultures that exist in isolation can be appropriated and there is a kind of subcultural tourism for whatever group; darkwave, garage, whatever.

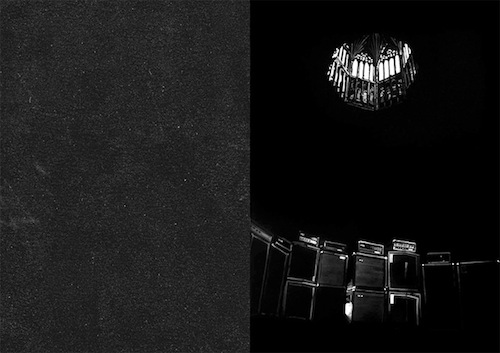

Bmoreart: From what I have read, you were raised in a religious household, and found heavy metal music as a teenager, which, to you, provided a more authentic collective spiritual experience. In your visual work, you borrow heavily from the aesthetics of both cultures to create an interesting hybrid. Why were these two cultures so influential for you? What do they share in common?

Terence: I think maybe religion sets itself up to try and welcome but at the same time it excludes. Most groups do this, they have to. They have to set up an other. I think at that time in the late 1980s metal seemed rebellious and it felt deep. Like you could dig infinitely and just get more extreme, faster or slower and more grotesque. Like you were challenging yourself, and it felt somewhat transgressive. When I went to college I studied religion and philosophy and realized that the dominant narratives buried even more intense and interesting heretical groups. It wasn’t really until I was in graduate school that I started to see that one, I wanted to make work about music and two, that I wanted to juxtapose it with my background in studying religious behaviors.

What they share in common I think is that each group, and this happens in all cultures, sets up what is profane and what is sacred. It’s very specific to each group. So in music there are just as many relics, holy days and heretics as there are with religious groups. That value is what intrigues me. That a 7″ record or a festival where a notable event or performance occurred has value outside of the event itself is what I enjoy.

Bmoreart: After doing local group exhibits at Nudashank, sophiajacob, loads of shows in Chicago, and a solo show at Stevenson University, you’re publishing a book! Why did you want to create a book version of your visual and written work? Lots of artists release monographs, but this project doesn’t come off this way – it seems to be an individual work of art in itself. In your opinion, what can a book do or offer that other art formats cannot?

Terence: Well I’ve been making zines and art books as part of my practice for about ten years. Off and on. So since 2010 I really fired it up and made one zine a month for a year. Then tried to calm it down. So I tend to make small editions now when I have certain ideas. I tend to treat each zine like an exhibition curated around an idea. For AYPS we started about a year ago collecting images and it just grew and grew into this collection of years of work.

I think a book can communicate an aesthetic or idea. I remember seeing Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations by Ed Ruscha for the first time and just that very simple organizing principle struck me. But I spent middle-school and high school making zines for hardcore and punk bands in Florida with my friends. So seeing this small intimate experience that encouraged a narrative made a lot of sense whether in the case of Ruscha or with Raymond Pettibon or Ari Marcopolous. So I guess to me that is what sets it out, scale, material and a narrative intent.

Bmoreart: The book is being published by Kiddiepunk, a multimedia group based in France. How did you find this publisher? Why did you want to work with them?

Terence: I knew Michael, the publisher, from his books he did with my friend and artist Scott Treleaven and with the author Dennis Cooper. So I really enjoyed these art books he did and that he stretched into the literary world with the book he did with Dennis. He asked me maybe two years ago to start working on this. It was a long simmer that just hit a boil.

Bmoreart: What are ‘negative texts’ ? How did they come about and what do they mean to you? How do they affect the images in the book?

Terence: I would just collect phrases, words, things I would associate with my themes in the drawings about anonymity, rapture, and so forth. I included them to challenge myself, its this part of my process, my way of organizing information. I would hope they could lend to the tone of the images. Some I negate even further by crossing them out since negation was such a big theme.

Bmoreart: The title of the book – Anno Yersinia Pestis Spiritus – or AYPS for short, sounds like a Latin phrase for ‘year of the evil spirit’ or something like that. (I just googled it – I was close.) I get that the phrase is an insider term for black metal albums of the 1990’s – but what does it mean to you? Why did you choose this title?

Terence: Yeah you got it pretty much. I think the intent when these musicians were using it was like “Year of our Spiritual Plague” and they were specifically using it to denigrate Christianity. So the phrase was interesting to me, I wrote it down and just kind of thought of it as this mantra. Personally I felt like I tend to not actually believe in very much, but I read a lot and traffic in this content. I think I have to, outside of my normal just skeptical nature, remain blank so I can receive and transmit the work. I chose it to try and get closer to understanding that void.

AYPS, which includes writing, images, and an interview with Terence Hannum will be available in mid-March from the publisher, Kiddiepunk, from Hannum himself, locally at Atomic Books, and at Printed Matter in NYC, “and a few other art book places around the world, and some record shops,” says Hannum.