A Personal Dispatch from “Black Panther: Rank & File” by Don Cook

This is not a review of art on the walls or installations in an art space. It is a meditation on a spirit that is – and yet is not – present and restless in the galleries of MICA through December 16. And it is also a meditation on the nature of fear.

Almost forty years ago I was a kid from Appalachia beginning my second year at the University of Maryland in College Park. By luck of the draw I was warehoused in the high rise dorms of student housing. And by the same luck a student named Karl was also warehoused on the same floor. Karl was a Black Panther and began to have party meetings on the hall.

As an Appalachian my contact with Americans of color and black culture was limited. In “Colored People,” a memoir of his own Appalachian childhood, Henry Louis Gates recalls that “Civil rights took us by surprise,” and that “TV was the ritual arena for the drama of race.” Henry Louis Gates grew up in a struggling mill town just twenty miles down creek of the bottomed-out coal town that was my home. Whole regions of Appalachia still remain isolated, and in the 50’s and 60’s that isolation was even more stubborn. It can be said that the people of Appalachia are insular and keep to themselves in part because the poor, regardless of color, always know their place, and know that the safest place is among one’s own kind. But it must also be acknowledged that in the era when Henry Louis Gates and I came of age the “place” of blacks in Appalachia was enforced not only by mountain culture and poverty, but also by the law of the land – as Gates says “the colored world was not so much a neighborhood as a condition of existence.”

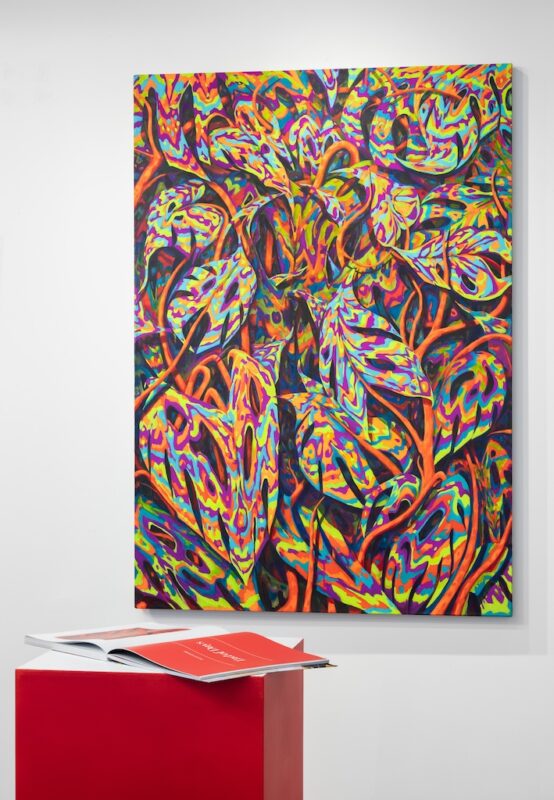

Edition by Kerry James Marshall

Edition by Kerry James Marshall

And so I remember being wonderstruck the first time that a contingent of Black Panther men and women marched down the hall to Karl’s room. I was wonderstruck in part because of the sheer physical beauty of their presence – a presence that was a perfect, breath-taking, and incendiary demonstration of militancy and hipness – Revolution made visible by radical chic. Admittedly, this mixing of militancy and fashion is a loaded, ambiguous strategy that has been used frequently and with a vengeance by both justice-seeking revolutionaries, and reactionary monsters – it is the taking on of a visual mantle of power that can stir, for good or ill, a fire in the mind and heart.

But the Black Panther Party’s visits to Karl’s room are more memorable because of the fear they conjured among the hall’s white population – and the nature of that fear when it was exposed. Panther movements on the hall were met with cracked doors, whispers about the presence of weapons on these visitors, and rumors of potential violence. What was remarkable was how very little it took for the imaginations of largely naïve, suburban, and frequently hipped-out white kids to revert to a primal fear that lurked in the hearts of the master and overseer class – the fear that Nat Turner was about to rise up and slaughter you as you sleep. And in conjuring up this demon among the whites, the Panthers’ message to the white population was clear – there is no exemption or exorcism from history; this ugly fear resides within you – deal with it.

Karl and I had several talks about the Black Panther Party before both of us moved away from the dorms, away from the University’s all-too parental eye. Karl was alert to the ways in which dramatic political action can be liberated from the conventions of theatrical entertainment. Several years earlier, during a year of community college back home, I had been part of a group of kids who had started a storefront theatre in the then dead-end railroad town of Cumberland, MD. We naively thought of ourselves as “radical,” “political,” even “brave.” We were none of these things, but I came away from the experience with an understanding of just how devilishly hard it is to detour theatre’s conventions into an engaging political presence – and I admired the way the Panthers had accomplished this hijacking of dramatic art. But mostly I remember Karl’s insistence, delivered with a mixture of patience, wit, and fury, that my education toward justice was sorely lacking, and would never really be complete – and could only be accomplished through my own curiosity and endeavor, not through some institution’s programming.

Madonna by Elizabeth Catlett

Madonna by Elizabeth Catlett

The Appalachian culture of my early childhood was still orally driven, and that tutelage remains inescapable. I know something is firmly in my head when it takes on “voice” – that a work of art can “speak to me” is a literal truth. Because of Karl I carry a collection of influential voices within me that might never have gained entrance to my spirit – and those voices of many colors are diverse and ever growing. They are voices that can open me onto experience. “Black Panther: Rank & File” threw me back to Benjamin Quarles’ “Blacks and John Brown;” back to the notebooks of Benjamin Banneker (which remain unpublished as a collected work), and particularly to his dream entries which are some of the finest mystical writings of America’s Romantic era. And it threw me back to the relentless passion of James Baldwin in “The Fire Next Time” – and to the following passage, which comes late in his book that was written in 1962, but remains a provocative march of contrary words onto the contemporary mind, startling the complacent, pleasure-seeking reader:

“Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not wish to face, and what white Americans do not face when they regard a Negro: reality – the fact that life is tragic. Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty in our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death – ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is a small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us. But white Americans do not believe in death, and that is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them. And this is also why the presence of the Negro in this country can bring about its destruction. It is the responsibility of free men to trust and celebrate what is constant – birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love, though we may not always think so – and to apprehend the nature of change, to be able and willing to change…

“I speak of change not on the surface but in the depths – change in the sense of renewal. But renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant that are not – safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope – the entire possibility – of freedom disappears. And by destruction I mean precisely the abdication by Americans of any effort really to be free. The Negro can precipitate this abdication because white Americans have never, in all their long history, been able to look on him as a man like themselves. The point need not be labored; it is proved over and over again by the Negro’s continuing position here, and his indescribable struggle to defeat the stratagems that white Americans have used, and use, to deny him his humanity. America could have used in other ways the energy that both groups have expended in this conflict. America, of all the Western nations, has been best placed to prove the uselessness and the obsolescence of the concept of color. But it has not dared to accept this opportunity, or even conceive of it as an opportunity. White Americans have thought of it as their shame, and have envied those more civilized and elegant European nations that were untroubled by the presence of black men on their shores…

Pirkle Jones Untitled Courtesy of Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Pirkle Jones Untitled Courtesy of Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

“This is because white Americans have supposed “Europe” and “civilization” to be synonyms – which they are not – and have been distrustful of other standards and other sources of vitality, especially those produced in America itself, and have attempted to behave in all matters as though what was east for Europe was also east for them. What it comes to is that if we, who can scarcely be considered a white nation, persist in thinking of ourselves as one, we condemn ourselves, with the truly white nations, to sterility and decay, whereas if we could accept ourselves as we are, we might bring new life to Western achievements, and transform them. The price of this transformation is the unconditional freedom of the Negro; it is not too much to say that he, who has been so long rejected, must now be embraced, and at no matter what psychic or social risk. He is the key figure in his country, and the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his. And the Negro recognizes this, in a negative way. Hence the question: Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?”

In order to be sanctified within the contemporary art space truly revolutionary activity must often be drained bloodless. And there is a certain bloodlessness to “Black Panther: Rank & File” (but Emory Douglas’ images don’t surrender an inch). What is more deeply disturbing, however, is just how restlessly this radical ghost dwells within its contemporary setting. James Baldwin’s statement “that life is tragic,” is a hard fact that cannot be smoothed out by education, discussion, or doses of Prozac – and in today’s America the fact that life is tragic is avoided – strenuously avoided. Admittedly, I do not share an optimistic view of our current cultural, educational, political, and social institutions’ ability to grasp and relay this tragic view because they often seek only to achieve some velvet compromise with such reality. No amount of packaging and finesse will ever make this tragic view palpable – and certainly never “enjoyable.”

Forty years from now if an exhibition documenting a slice of our own time were installed in a future MICA what would it offer? My fear is that in forty years, or less, an exhibition about the forces of change at work in our own particular culture might seem as if it were scripted by Lewis Carroll, rather than Angela Davis or Huey Newton. It would offer a world of reverse revolution, where the barricades are erected by the Soldiers of the Status Quo to guarantee and protect the Noble Assets of Affluence, Security, Eternal Life, Tariffed and Licensed Knowledge, and Perfect Corporate Poise.

These barricades are too high to easily leap, too thick to readily dismantle – either from without or from within. I fear that our compromises, privilege, avatars, guilty pleasures, virtual realities, and even our good intentions are adding up to a form of steadfast waywardness. James Baldwin takes his title, “The Fire Next Time,” from a biblical passage in which God reminds Noah after the flood that if the world does not mend its ways, if human kind does not resume its history with a consciousness of Justice, the next cleansing deluge will not be by water – but it will be “the fire next time.” I fear that the next generation may see us as reckless children, foolishly stirring the embers of the fire next time.