When I met Raoul Middleman in the gallery my first mistake was calling it a retrospective. “This?” He said, gesturing around him. “This is nothing!” After I pointed out that the show encompassed forty years of painting, from his earliest pop leanings in 1965 to landscapes painted in 2007, he reconsidered. “It’s a mini-retrospective, maybe.”

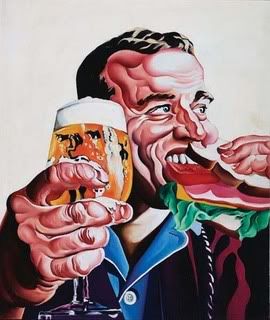

The first piece that jumps out in the Grimaldis Gallery exhibit of forty or so works is ‘Midnight Snack.’ In the sixties, Middleman lived in New York and ran with the pop art pack, including Warhol and Lichtenstein. There’s a grotesque feel to the hungry teeth gobbling down a sandwich and a beer that fits with the rest of the work in the show, but stylistically, this piece is a sore thumb. Its flat, bold colors seem garish and insensitive, compared to the deft grays, browns, and earthy blues that populate the rest of the body of work.

So what happened? I asked, thinking he would give me a smug answer. What changed for you? I sometimes hate talking to mature, especially male, artists because of the egos I have encountered, so I expected as much. Raoul looked at me, considered the questions, and I swear I saw a twinkle in his eye.

“I love Baltimore,” he started. “I was born here and grew up, thinking I would be a writer, hanging out at the burlesque shows on the block, drinking on the inner harbor piers. New York was great, but it wasn’t for me. Pop Art didn’t satisfy me… I needed to do my own thing and in New York you have to run with a pack. New York painters have to be more focused, and more mean. You have to stick to a style to pay your rent.”

“Baltimore has a perverse decay,” he continued, “a lyrical decadence. I absolutely love it here. Baltimore is elegant, trashy, wild … I bought my home here in 1975 for a dollar and have been here since. I didn’t have to do any one thing, but just paint the things I wanted to. I had the chance to develop a painting language that works for me without stressing out over the product or presentation. I like to show my work in New York, but I like making it in Baltimore.”

Looking over the collection of paintings in the gallery, one either loves or hates this work. There is a nervousness and a quickness, a sense of rash decision-making and enthrallment with the act of making them. Also, and I think this relates to Middleman’s opinions of Baltimore, a dirtiness and a darkness that pervades. It creeps through his landscapes in shadows and approaching storms, it beckons from dark pathways, it licks over his figures, masking them in mystery and ambiguity. There is a sense of humor in these works that balances out the darkness and keeps them from being gloomy. When I ask about this, Middleman admits he is a “burlesque comedian” at heart.

We take a look at the paintings in the gallery and several bodies of work emerge: the huge narrative works that employ multiple figures in imaginary, possibly mythological, settings, the plein air landscapes of Italy and Southern Maryland, the self portraits, and then the still lives, mostly of copper pots, lemons, and dead fish, which make visual sense without a specific narrative involved. Irrelevant of subject matter, the consistency of Middleman’s color palette and rich, crusty painted surfaces tie the work together. When I ask about the importance of materials, Middleman is happy to divulge his secrets.

“I used to mix my own paint for thirty years,” he confides. “Sometimes I’d take three or four hours setting up a palette for a plein air painting that took an hour to paint. The pigment of the paint, the texture and consistency of it has got to be just right because I work so quickly. When I slow down, things get overworked. And, for me, that is deadly.”

We leave the gallery and visit his studio, a sprawling two-story warehouse space in the Copycat area. I had intended to ask him what his secret was, the secret to a forty-year-plus painting career, but when we get to his studio, I no longer need to. It is obvious: He LOVES it. He simply loves doing it. There are thousands and thousands of paintings there, neatly stacked and categorized into racks that you’d need a tall ladder to navigate. It’s incredible and overwhelming.

Raoul shows me more paintings he’s just completed, and his plans for works on paper for an upcoming show in Israel. He’s talking and gesticulating and pulling out other huge narrative works and telling me about them. He’s most excited about his newest paintings, still-wet still lives of fish and lemons, where he’s working out compositions and color relationships, painting over old paintings, and using deep purples instead of browns. He tells me about a new mural he painted at Zen West, a new bar and café that opened in Belvedere Square, and a mural he just had installed at the Baltimore Convention Center.

Its energizing being there, in the midst of frenetic production and a raw sort of joy, years and years of working on the same problems and issues in paint, and loving it. Of course, there is the dark side. “Doubt and despair are essential elements,” he acknowledges. “You always have to ask a new question, and risk failure, and that can be draining. But, if that isn’t in the work, its just decoration.”

I ask Middleman a few questions about the commercial side of the art business, about those things, which are considered too ‘common’ to talk about in art school. How do you balance the working artist part of your self with the world of competition and snobbery and money? We talk about successes and failures, the merits of both, and he tells me a story of his first commissioned portrait.

“When I was just starting out a woman came to my studio and asked me to paint her portrait. I agreed and we set a price, based on time and materials. She sat for me a couple of times and was happy with the portrait. She came back a couple of weeks later and asked me to ‘soften’ some of her features, which I did. Then she came back a few weeks later, to have me change one or two other things, which I did. And then, a month or so later, she came back again.

To me, the painting was getting worse and worse, less solid and more vague, and, this last time, scraping off a layer of paint, I punched a hole in the canvas. White paint started oozing through it like toothpaste and it was ruined. The woman asked for her money back and I agreed. It was a lesson well learned. Now, I am careful about who I do portraits and commissions, if any, for. I know that pleasing someone else is never going to happen unless I am truly engaged in the work. Maybe this turns off some potential clients, but that just isn’t the kind of work I want to do.”

What about fame? What about solo shows and getting your name out there? Again, Middleman was happy to share his opinions. “Fame can be a viper of self-interest. It’s insatiable. Once we get some attention, especially artists, we can’t help but want more. But then, if it becomes your focus, you can loose concentration on the work, which is what it’s all about. But, it’s also important to show your work. It’s very satisfying to sell work. I think its important to keep a balance, but try to stay grounded in your studio practice.”

There’s something healthy and exciting about speaking this honestly about what it means to be an artist and to make a career out of it. I ask Raoul once more about the issue of failure. All of us in this field experience it so much and so often – rejection letters in the mail, competition in the job field, jurors who don’t see the merit in our work, the necessity of sometimes making bad paintings – it’s so tough. “Sometimes the world smiles on your efforts and other times you fail. Failure motivates one to keep on trying; it establishes a future and possibilities of discovery. Success is a cop-out to commodity. The teacher who doesn’t practice the craft doesn’t experience failure, therefore, has only smug answers in the hip pocket and parcels out to students conventional banalities and trite formulaic procedures of academic ilk. Without failure art cannot renew itself and becomes surface manner.”

Although Raoul Middleman’s paintings have luscious and exciting surfaces, they are far from ‘mere surface’. An ever-evolving process, these works continue to challenge and confound their maker, always generating new ideas and problems to solve. After forty-two years, Middleman’s next painting is just as important as it ever was. And this, to me, is the most exciting part.